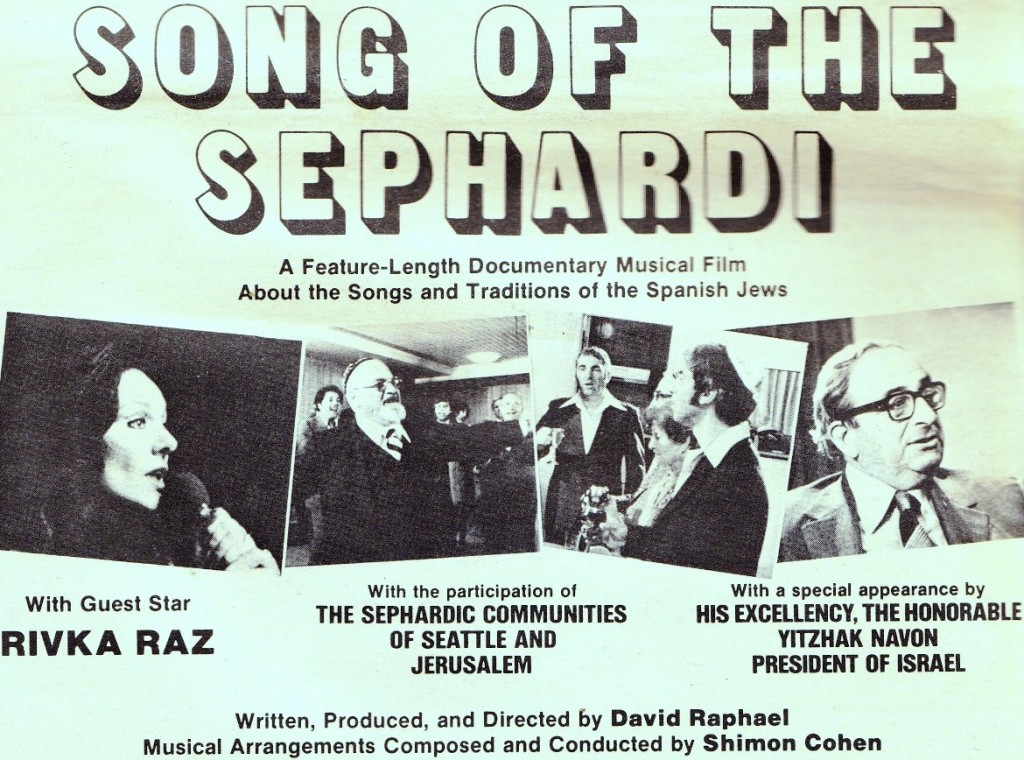

Song of the Sephardi advertisement from The Jewish Transcript, 1978.

In anticipation of the Fourth International Ladino Day to be held at the University of Washington on November 30, 2016, we offer a preview of what’s in store. We will be showing an excerpt from the 1978 film called Song of the Sephardi. Released in 1978 with a premiere at the Seattle Center Playhouse, the film provides a glimpse of Sephardic and Ladino culture in Seattle more than a generation ago. Nearly forty years later, we revisit the film, reflect on the snapshot of Sephardic culture it captured, and follow the protagonists and the families featured in the film: Where are they now? And what is the present status of Sephardic culture and community in Seattle? Are there more verses to the “song of the Sephardi” yet to be composed?

Song of the Sephardi began as a dream in the imagination of director David Raphael, a graduate of the University of Washington medical school who was living in Seattle in the 1970s and ensconced in the local Sephardic community. In 1978, in anticipation of the release of the film, he shared the following remarks with the JTNews (August 24, 1978; special thanks to Lilly DeJaen for sharing the newspaper clipping):

Producing a film is very much like producing a baby. Its original conception lies in the seed of an idea borne out by love, and is sometimes promoted by vaguely defined frustrations. The idea of making a film about the Sephardic Ladino tradition occurred to me when I was a senior student in the medical school at the University of Washington in the fall of 1975; it was perhaps not the best of times for its attempted realization.

What I had in mind at the time was a 20-minutes film of limited scope to be titled “Sephardim: The Spanish Jews of Seattle.” However, my efforts to raise the funds for the film, both from local and national agencies, were unsuccessful.

The motivation for the making of such a film was two-fold:

1) It sprung from a deep love and appreciation of the Sephardic Judeo-Spanish tradition with which I had come into close contact while living in Seattle.

These feelings were fostered and strengthened by individuals such as Rabbi Solomon Maimon and Reverend Samuel Benaroya. To them as well as others in the community, I owe a debt of gratitude for their imparting to me a love of the tradition that they hold dear.

2) As a Jewish Information Society activist on the University of Washington campus, I had been involved with the weekly cultural programming of its activities.

This gave me an opportunity to exhaustively review and extensively use much of the audio-visual materials produced by the Jewish establishment.

Much to my dismay, I found that there was not a single film that dealt with the Sephardic Ladino tradition.

I resolved to rectify, to the best of my ability, this glaring deficiency as soon as time, circumstances, and finances allowed me to do so.

In the meantime, I learned all that I could about filmmaking: reading textbooks and taking courses on cinematography, making practice films, etc. It was the least I could do while I counted times.

Now or Never

At the end of my internship, I felt that it was now or never to undertake this cinematic venture. I started working in an emergency room and used practically all of my free time to work on the film.

Many of my friends, I must admit, thought it to be a foolhardy enterprise. Looking back over the last year, I cannot deny that I grossly underestimated the difficulty as well as the cost of such a project.

But I doubt that such knowledge and foresight would have deterred me from making the effort; at most, it would have resulted in my scaling down the size of the film.

Song of the Sephardi

I was determined not to make the run-of-the-mill documentary full of long-winded narrative explanations. In order to counter the slow-paced tedium of a straight documentary film, I decided to enliven the film with musical production sequences such as one might encounter in a musical; such sequences would attempt to portray visually, either in a traditional or contemporary sense, the lyrics of the Ladino (Judeo-Spanish) folk songs that had been preserved by the Sephardim since the expulsion from Spain in 1492.

The film, therefore, would be a musical as much as it would be a documentary. Using an alternate title that I had considered back in 1975, I decided to call it “Song of the Sephardi.”

Half of the film deals with the Sephardim of Seattle and involves the participation of both the Sephardic Bikur Holim and Ezra Bessaroth congregations. Many of the film’s participants donated freely of their time.

Seattle Sephardic community members at Sephardic Bikur Holim.

What was surprising was that certain individuals, such as Rabbi Maimon and Cantor Ike Azose and a host of other ‘undiscovered’ movie stars, demonstrated a natural gift for acting.

Special assistance was provided to me by Ben-Zion Maimon who helped me decipher some of the Turkish words used in certain Ladino folk songs, and also by Cantor Azose who helped in preparing the Ladino transliterations for the Passover scene.….

Yitzhak Navon

I cannot end without mentioning my good fortune that October in approaching Yitzhak Navon, then a member of the Israeli Knesset who then agreed to appear in the film in order to discuss the status of Ladino culture in Israel.

Six months later, Navon was elected president of Israel.

The film is no longer a baby; it has grown into a 75-minite-long motion picture. On Sept. 10 [1978] at the Seattle Center Playhouse, the film will be Bar Mitzvah’ed in from of the mother community of Seattle that will finally have an opportunity to determine whether this unusual cinematic offspring has truly come of age.

At the opening night for the film, Cantor Isaac Azose offered the following words of introduction (which Mr. Azose has kindly shared with us):

Good evening, ladies and gentlemen. Welcome to The Seattle Center Playhouse. My name is Ike Azose and this evening, we are privileged to present the World Premiere of a musical documentary, “Song of the Sephardi”. As its title hints, the movie is about the Sepharadim, or more specifically, Jews who populated the Iberian Peninsula during the 10th through 15th centuries and were finally driven out of Spain, (those who did not convert to Catholicism, that is), in 1492 by King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella.

During their sojourn in Spain, these Jews, these Sepharadim, spoke a medieval Castilian dialect, which they had retained even after the expulsion from Spain. Other countries in the Mediterranean basin, primarily Turkey, welcomed them with open arms.

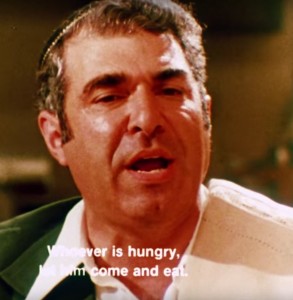

Hazzan Isaac Azose reading the Passover seder in Ladino.

It is interesting to note that the Sepharadim, among whom I am proud to number myself, have retained that medieval Castilian dialect called Ladino, Judezmo or Judeo-Espanyol down through the centuries to the present day, where it has been enriched, if that is the right term, with the addition of several words of the language of the countries in which they lived.

This film, then, is about some of the songs, the customs, the traditions and the ceremonies of the Sephardic Jews.

A word about Dr. David Rafael, the writer, producer, director of this film. His original idea was to produce a short 20-minute film on the customs and traditions of the Sepharadim of Seattle, which is considered to be one of the more traditional Sephardic communities in the United States. He was amazed that no films of this nature were available or had been made. As he became more deeply involved, he decided to expand upon the original concept and worry about the financing as he went along. This was no longer a dream for him; it became an obsession, the end result of which we will see here tonight…

I’m sure that David would agree that a lot of the credit for the making of this film belongs to his long-suffering wife Esther, who has had to endure several absences from David of many days’ duration, primarily because he had to arrange his medical schedule (which was, after all, his prime source of personal income), to suit his film-making schedule. In attempting to obtain financing for the project, he was given the cold shoulder by certain organizations, both local and national, which should have been prime sponsors. This did not discourage Dr. Rafael. On the contrary, it enforced his determination to proceed…

Links for Further Exploration

- RSVP for Ladino Day 2016

- Enjoy video highlights from our previous celebrations of International Ladino Day in Seattle

I checked the video out from the main Seattle Library and returned it. When I went later to take it out, they said it was lost. I was very disappointed. Much later I found it on the internet and I believe that I downloaded it. I will look for it after Shabbat. I admire the work that you are involved in and look forward to more in the future. Shabbat Shalom.

Hi Ovadya,

Pretty sure that “Song of the Sephardi” is available for free on the internet or youtube. Visit http://www.CarmiHouse.com for more information. They are the current distributors for the documentary.

Thank you for wonderful interview of my father Dr David Raphael. He loved the Sephardic Community of Seattle and proud of his Sephardic roots on his maternal tree. In his free time wrote books on the history of Spanish Jews.