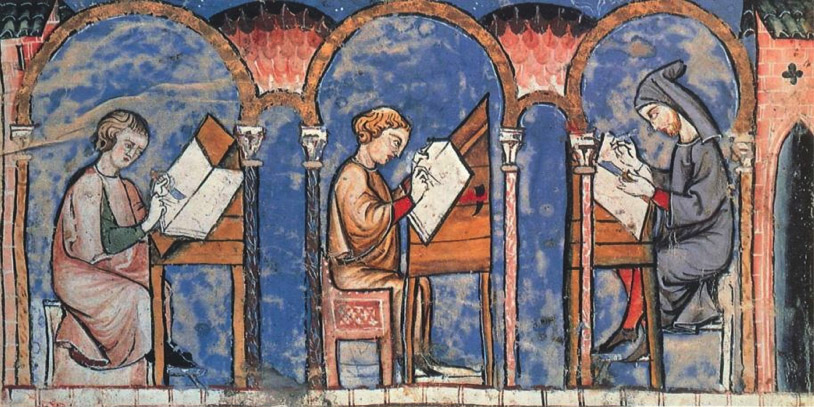

Jewish scribes depicted in the famous Libro de los juegos (“Book of games”) commissioned by Alfonso X in 1283

By Vivian Mills

During a seminar on Sephardic culture before 1492 taught by Prof. Ana Gómez-Bravo, I came across the name of Shem Tov of Carrión, a Jewish Castilian poet from the fourteenth century who had written a wisdom poem of great skill in the Castilian vernacular — the language that a few centuries later would be known as Spanish — called Proverbios morales or Moral Proverbs.

This poem follows the tradition of the great works of wisdom in Latin, Arabic and Hebrew such as the Biblical book of Ecclesiastes and The Sayings of the Philosophers. The work is dedicated to King Peter I of Castile (1350-1369), the son of Alfonso XI (1313-1350) and the great-grandson of Alfonso X, also known as the Learned King.

It puzzled me that I had not heard about this poet before. His name was never mentioned in the specialized seminars I had taken about medieval literature and culture in Castile during the Middle Ages. I had learned about Fernán González, Pelayo, and el Cid Rodrigo Díaz de Vivar, the epic heroes that traditionally have been considered the cornerstones of Spain’s national identity. I had also learned of Berceo, Don Juan Manuel, Juan Ruiz, Rojas, Manrique and other medieval authors and poets whose works have withstood the test of time and who are still being studied today. But I had not heard of Shem Tov, or Sem Tob de Carrión (as his name is styled in Spanish).

1947 version of Shem Tov’s “Proverbios morales”

I was intrigued, not only because of my interest in the Sephardic Jews that lived in Iberia from the 5th – 15th centuries, but also because I knew that during the fourteenth century — following the Hebrew revival that came about during the twelfth century in the courts of Al-Andalus under Muslim rule — the language of prestige for the Jews of Castile was Hebrew. Why would Shem Tov go so far from the norm and write his work in Castilian? I decided to investigate this puzzling Iberian Jew who wrote poetry in Castilian.

In the course of my research, I found that we know very little about Shem Tov other than what he wrote about himself in his poem.

Some critics, like the late Yitzhak Baer, have identified him with the historical figure of Shem Tov ben Yitzhak Ardutiel, a prominent rabbi and author that lived in Carrión de los Condes, a flourishing Jewish community along the Camino de Santiago pilgrimage route that boasted its own rabbinical school.

There are a few works in Hebrew that have been attributed to Rabbi Ardutiel, among them the maqama (a fictional composition that alternates between prose and poetry and often has a humorous or satirical nature) known as The Rabbi’s Tale or The Battle of the Pen and the Scissors, Yam Kohelet or The Sea of Ecclesiastes, and a viddui, a penitential prayer used in Sephardic Yom Kippur ceremonies.

But there is nothing known for certain about Shem Tov, and his identification as Rabbi Ardutiel is not irrefutable, though as medievalist John Zemke argues, “a preponderance of circumstantial evidence gives the identification the force of ‘moral certainty.’”

What is certain about the literary figure of Shem Tov — or Santob, as he styled himself — is that he was a Jew that lived in Castile during a time of political transition and uncertainty for the Jews of Castile, as the old king, Alfonso, had passed away and his heir, Peter, was establishing his reign.

The central square of Carrión de los Condes today.

In his poem, Shem Tov petitions the king to settle his father Alfonso’s debt and reminds King Peter of the moral obligation he has to protect the Jews of Castile, as their lives and safety depend upon being considered “the king’s property.” He exhorts his king to follow in the tradition of his predecessors, who had extended their protection to the aljamas (Jewish settlements) of Castile.

Shem Tov then embarks on a literary reflection that touches on humanity’s fallibility and insignificance in the face of divine greatness, reflects on what makes a good man and the dangers of relying on fortune’s whims, as tragedy and affliction happen to all — even those who perform good deeds — and reminds readers that righteous acts and benevolence should not lead to complacency, because the world is a complicated place.

This reflection starts in a personal place, with a poetic voice that moves from a confessional first person to second person dialogue, then travels to a collective identity that represents Shem Tov’s community, the Jews of Castile. Shem Tov closes the poem by listing the qualities that make a good ruler and bringing up once more the merçed, or favor, the new king owes him and the Jews of Castile—his protection and goodwill.

The themes Shem Tov covers in his Proverbios morales are universal and timeless. His verses reflect upon greed, vengeance, righteousness, tragedy, affliction and more. Moreover, his poetry is beautiful and easily remembered. In these times, where we want the newest, fastest, most fashionable gadgets, clothes, cars, etc. — and in our hunger for these material things have put our own planet in jeopardy — I find that some of his verses could have been written today:

Alabaster statue of King Peter I of Castile circa 1504

I find in this world two [kinds of] men and no more, and I can never find the third:

A seeker who seeks and never finds, and another who is never content with whatever he finds.

One who finds and is satisfied I cannot find; such a one I would call truly fortunate and wealthy.

For there is no poor man except the covetous one, nor a wealthy man except one who is content with what he has.

He who wishes [only] what he needs will be satisfied with little; but he who would like more than he needs, the [entire] world will not suffice.

[When a man uses] what he needs, he uses his own substance, but whatever exceeds these needs enslaves him his whole life long.

The whole day long he is exhausted, hounded to get it, and through the night he is anxious out of fear of losing it.

He derives less pleasure from seeing what he has than pain from the fear of losing it.

He is unsatisfied, even though he has more than can fit into coffers of moneybags; and he labors without knowing for whom he accumulates.

Translations by T.A. Perry, from The Moral Proverbs of Santob de Carrion: Jewish Wisdom in Christian Spain

In our times, when political upheaval and blatant abuse of power are weakening hard-won victories of equality and freedom around the world, Shem Tov’s words to his king, in which he praises the value of prudence, restraint, and benevolence in those who are in a position of authority, have not lost their resonance:

Power, if cruel, is an ugly half: may God never grant length to such a vestiture!

For were it very long, it would shorten many; and he who would wear it would divest many.

Power, with benevolence, is a very lovely thing, like the whiteness of a face when mixed with red:

Benevolence, which raises up simplicity and good sense, and power, which crushes haughtiness and folly.

There are two that sustain this world: one is the law, which is commanded; the other is the king,

Whom God placed as a guardian so that none would go against God’s commandments (unless he incurs punishment),

To prevent people from planning evil and the strong from devouring the weak.

It is my fondest wish to see the poetry of Shem Tov take its rightful place alongside the works of other Castilian writers that have withstood the test of time. The beauty of Shem Tov’s words and the wisdom they impart are part of our legacy. They should not be lost or forgotten, for they speak to us about issues that are as relevant today as they were in the past.

Shem Tov’s Proverbios morales teach us about the fickle nature of fortune, of the value of wisdom, humility, and prudence. Above all, Shem Tov emphasizes the value of speaking out when faced with adversity, and our duty to hold the powerful accountable for their actions. Through his words he demonstrates that we are the most powerful advocates for our own well-being.

To lose a work like this would be a great tragedy, for not only for those of us who love that most sublime of arts, poetry, but for all.

Vivian Mills, Richard M. Willner Memorial Scholar, is a second-year PhD student in Spanish and Portuguese Studies at the University of Washington. She was born in Ecuador and moved to the United States with her family at the age of sixteen. She received a BA in Business Economics and an MA in Spanish from the University of South Florida. Her research focuses on identity and the building of textual authority in the literary works of Jewish, Converso and Morisco writers of late medieval and early-modern Iberia. Her latest research focuses on the works of Shem Tov of Carrion, a medieval poet and rabbi. When not reading poetry, you can find Vivian at work in her garden or spending time with her family.

Vivian Mills, Richard M. Willner Memorial Scholar, is a second-year PhD student in Spanish and Portuguese Studies at the University of Washington. She was born in Ecuador and moved to the United States with her family at the age of sixteen. She received a BA in Business Economics and an MA in Spanish from the University of South Florida. Her research focuses on identity and the building of textual authority in the literary works of Jewish, Converso and Morisco writers of late medieval and early-modern Iberia. Her latest research focuses on the works of Shem Tov of Carrion, a medieval poet and rabbi. When not reading poetry, you can find Vivian at work in her garden or spending time with her family.

Dear Vivían Mills,

Congratulations on your excellent piece of research.

I am Spanish and ashkenazi Jew and I find wonderful people like you so interested in Iberian Jews, the culture, art and history of my people, mostly taken into account the absolute lack of interest for us here in Spain. I really appreciate it personally

Thanks so much for showcasting the world a part of a very significant culture.

I wish you the very best in your career.

FYI my family never left Spain as part of the diáspora, we are not religious and we are the typical western europeans.

Thank you, Ms. Velasco, for your kind words. I am really happy that you found this post interesting. I hope that through my work, I continue to spark the public’s interest in the works of Sepharad.

Best wishes,

VM

Eva, naci en España en 1943 y mi familia se mudó a los EEUU en 1956. Gradué de la Universidad de James Madison Y fui a la Universidad de Virginia donde estudié Literatura Hispánica con una concentración en literatura medieval de Espana haciendo incursiones pequeñas en literatura portugués de esos tiempos. Cuando descubrí comunidades de Sefaradim en el internet, me hice parte de ellas porque adoro su lengua y cultura. Aunque hace ya muchos años que dejé esa parte de mi vida, todavía añoro esos estudios. Me he enamorado del articulo y me interesaria hacerme de Proverbios Morales de Shem Tov si es posible

Estimado Antonio:

Por supuesto. Póngase en contacto conmigo a través de mi correo electrónico para así poder hacerle llegar una copia. Me alegra mucho que le haya gustado el artículo y espero que la lectura de los Proverbios morales le sea de su agrado.

Siempre es un placer comunicarme con un colega amante de la literatura medieval,

Vivian

Dear Antonio,

Of course, If you contact me through my email address I can arrange for a copy to be available to you. I am very glad you liked the blog post and I hope reading the Proverbios morales brings you joy.

It’s always rewarding to get in touch with a colleague who loves medieval literature,

Vivian

Dear Vivian,

Nearly four years ago I was asked by my network to translate into French a review by Adelto Gonçalves* of Matula the latest book of poems by Brazilian poet Moacir Amâncio (São Paulo 2016).

I’m not sure how directly relevant the book itself might be to the theme of your study, but the title of the review might arouse your curiosity:

« Diálogo com a Ibéria hebraica na poesia de Moacir Amâncio ».

Here’s a link to the original article in Portuguese, as I have no reason to think that you would find it more interesting in French :

« http://www.tlaxcala-int.org/article.asp?reference=19553 ».

At the end of the review you will find some biographical elements as well as a list of works by Moacir Amâncio.

*Doutor em Letras na área de Literatura Portuguesa pela Universidade de São Paulo (USP) e mestre em Língua Espanhola e Literaturas Espanhola e Hispano-americana pela USP.

Best regards,

Jacques Boutard, member of Tlaxcala, the international network for linguistic diversity

This is an amazing piece of research. Thank you so much for your work. Shem Tov’s wisdom is timeless and, as you stated, in today’s world its morality carries more weight than ever.

Estimada Vivian,

Qué lindo volver a leer lo que escribiste. Aprendí mucho. De verdad te felicito. Excelente trabajo.