By Michael A. Rosenthal

War is a frightening and terrible experience for those who have to endure it. However, in the autumn of 1914, when the First World War began, many Germans, perhaps naively, embraced it with enthusiasm, because they believed that society would be transformed through the experience of struggle. A majority of German Jews, businessmen and intellectuals alike, shared these sentiments, at least at the beginning of the war.

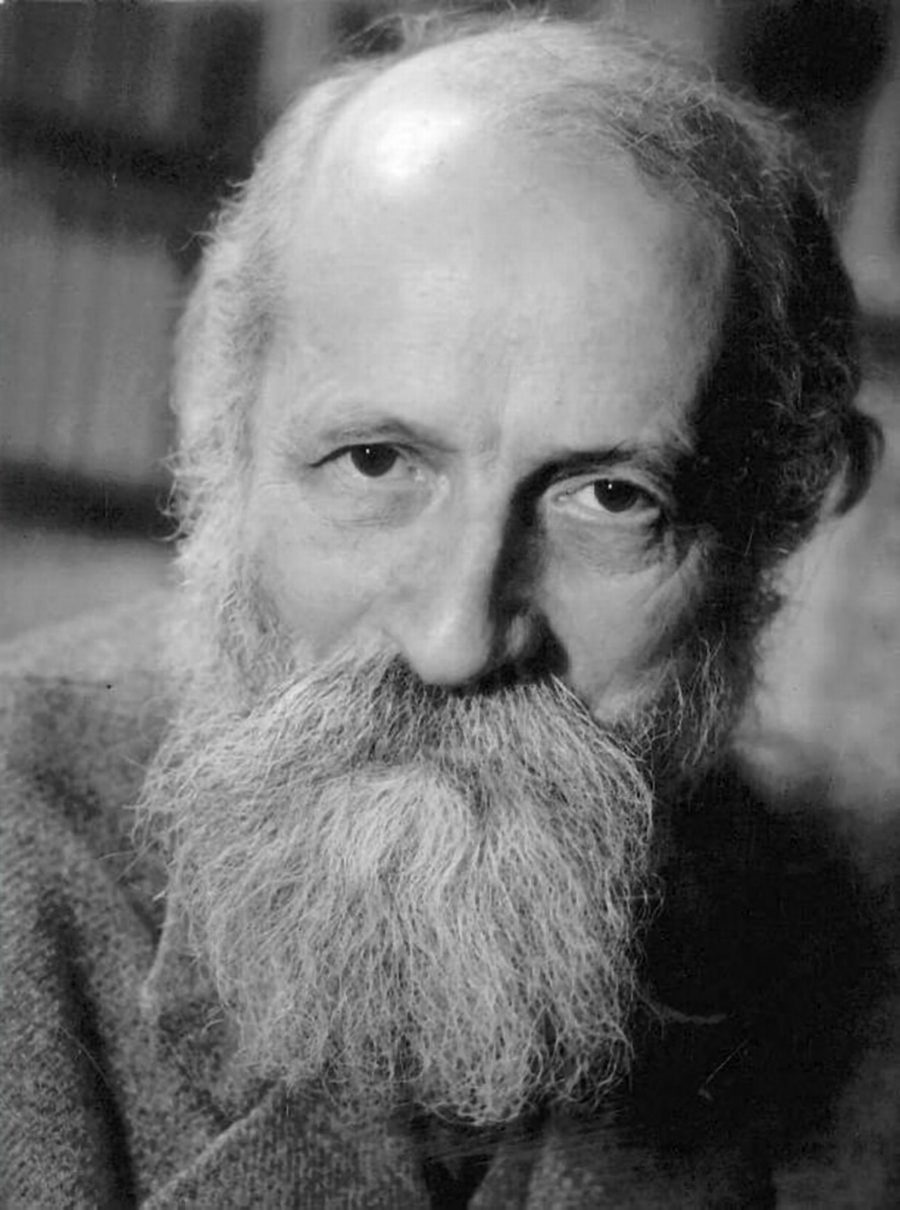

The Jewish philosopher Hermann Cohen, 1842-1918.

In the midst of the war, Hermann Cohen (1842-1918), the most prominent Jewish philosopher in Germany, launched into a series of published disputes over the nature of Biblical prophecy. It began with a strident critique of the seventeenth-century philosopher Spinoza, and extended to arguments with his contemporaries, the protestant theologian Ernst Troeltsch, and the renowned thinker Martin Buber.

It might seem that these debates were scholarly and far removed from the urgent struggles on the battlefield. However, Cohen was ultimately concerned with a pressing existential issue: the debate over the nature of prophecy actually addresses whether it was possible for Jews to be citizens in the new German state, which would result from the war.

In 1915 Cohen published a vigorous attack upon the philosophy of Spinoza, who had been banned from the Sephardic community in Amsterdam on account of his “monstrous heresies.” He accused the seventeenth-century philosopher, whose ideas were enjoying a renewed popularity centuries after his death, of having attacked the fundamental principles of Judaism and betrayed the Jewish community for the sake of revenge.

Nowhere was Cohen’s critique more pointed than on Spinoza’s idea of prophecy. Spinoza challenged two of the dominant, though conflicting, views of prophecy in the Jewish tradition: some claimed that it was fundamentally rational, others that it had authority over and above reason. Spinoza argued that the prophets like Isaiah, Elijah, and Ezekiel were not philosophers, but rather gifted speakers animated by the good of their community. He also argued that Scripture was not an authority in itself but an invention of human beings for moral and political purposes.

Cohen defended the philosophical conception of prophecy against Spinoza’s attack. According to Cohen, the prophetic voice of revelation was fundamentally rational. He agreed with Spinoza that the purpose of the revelation was moral rather than metaphysical. But he thought that Spinoza had sold morality short as a system of practical guidance and advice in a world bereft of God’s guidance.

Instead, following Immanuel Kant, Cohen argued that the moral voice of the prophets was in the form of a “categorical imperative”: a command to act, understood through reason to be binding on myself and all other human beings. Thus, Cohen’s idea that the prophetic voice of Judaism was moral dovetailed with the ideals of the German Enlightenment. It also solved a pressing political problem, one that became more urgent to Cohen as the war effort faltered and more extremist elements reared their head, often against the Jews.

A Biblical Basis for Citizenship

An 1894 German edition of fairy tales by the brothers Grimm.

Cohen had always looked for a source of German political identity that could include the Jews. When the Germans became a state in 1871, they drew on a variety of sources to forge a national identity. One was cultural ideal exemplified in either folkways—like the stories collected by the brothers Grimm—or high art—such as the exemplary German genius, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. Another was the claim of a common blood rooted in the quasi-mystical past of those Germanic tribes who had resisted the Roman conquerors in the Teutonic forests. Finally there was the moral ideal propagated by the Church or the Enlightenment philosophers, such as Kant.

Obviously Jews were excluded from citizenship based on bloodlines traced back to a past that by definition omitted them. However, they had a chance at the other two criteria. Many Jews in Germany became followers and propagators of the cult of Bildung, the idea of cultural education culminating in self-transformation. They also could claim a direct link to the source of Christian morality through the prophetic tradition of the “Old Testament,” which had inspired not only thousands of years of Jewish life but also the Protestant Reformation in Germany. It was the aspirational ideal of a life lived according to the prophetic sources that Cohen believed could unify all Germans, whether Jew or Christian, in a new political dispensation.

Cohen had to contend not only with Spinozists who undermined the philosophical basis of this ideal, but also with Protestants who believed that the testament of the life and death of Jesus Christ had superseded the prophets. This old theological doctrine—called “supersessionism”—also had its philosophical dimension. Cohen had to argue against his own primary philosophical inspiration, Immanuel Kant, who had denigrated Judaism and claimed that only a purified Christianity could approach the moral ideal.

This discussion had undergone a curious transformation in the early twentieth century and was renewed during the crisis of the war. Max Weber was one of the founders of modern sociology in Germany. He published a series of articles from 1917 to 1919 on “Ancient Judaism,” in which he applied the tools of modern social science to the Bible. But it was the theologian Ernst Troeltsch who mostly preoccupied Cohen. Influenced by Weber, Troeltsch claimed that the Hebrew prophets belonged to a rural culture, while Jesus represented a more urban phase of social development. So, because Germany was in the process of industrializing, the relevance of the Jews who clung to rural ideas had been superseded by urban Christianity. As long as they clung to their archaic faith, Troeltsch’s argument went, the Jews were not morally fit for citizenship.

Cohen did everything that he could to combat this modern notion of supersession based on social science. He and his protégés argued that the sociological approach entirely missed the moral content of prophecy, which remained as powerful as ever, both for Jews and Christians.

Buber’s Zionism versus Cohen’s German Liberal Nationalism

The philosopher Martin Buber, 1878-1965, was influential in Zionism and existential philosophy.

If these Protestants weren’t difficult enough, Cohen also had to contest with another political tendency within the Jewish community, which also claimed inspiration from the prophets. Martin Buber was an ardent Zionist, who believed that the possibility of Jewish cultural renewal depended upon political independence. Though he did not emigrate to Palestine until 1938, when he became a professor at the Hebrew University, Buber was skeptical about the possibility of a meaningful cultural and political life for Jews within Germany. During the First World War, he believed in a quasi-mystical idea of re-experiencing the prophetic ethos by establishing and inhabiting a Jewish homeland.

In a heated exchange, Cohen dismissed Buber’s ideas as unduly pessimistic and confused. Cohen believed that Jews had transformed their sense of morality and nationhood through their interaction with German culture and the nascent modern state. In his view, the prophetic vision led to the call for a socialist democracy. With its capital in Berlin, Germany would be a beacon for all people, including Jews.

As the tide of war turned against Germany, so too did sentiment against the Jewish population. Right-wing figures in the Ministry of War circulated the rumor that Jews were shirking their patriotic duty. They organized a census of the German Jewish population to see how their rate of service in the war compared to their compatriots. The census achieved its propagandistic goal—to circulate the idea that Jews were unpatriotic—even though its results proved otherwise.

Hermann Cohen had suffered the indignities of anti-Semitism before and, even in his senescence, he again rose to the occasion. As his critique of Spinoza and the exchanges with Buber and Troeltsch show, he vigorously defended to the end the prophetic vision of a just state in which all could participate as equals.

Cohen died in 1918 just before the Weimar Republic was founded. The corrupt German empire was transformed into a parliamentary democracy in which, at least in the beginning, Jews enjoyed unprecedented prominence and success. But the very nationalist forces that Cohen had embraced at the beginning of the war were poisoned through defeat and economic collapse. The Weimar Republic became increasingly weak and was ultimately overthrown by the Nazis. The prophetic legacy that Cohen worked so hard to articulate and defend remained unfulfilled.

For Further Exploration

- Event page for the Conference on “Spinoza and Modern Jewish Philosophy,” organized by Prof. Michael Rosenthal, which will take place at the UW in May 2017

Leave A Comment