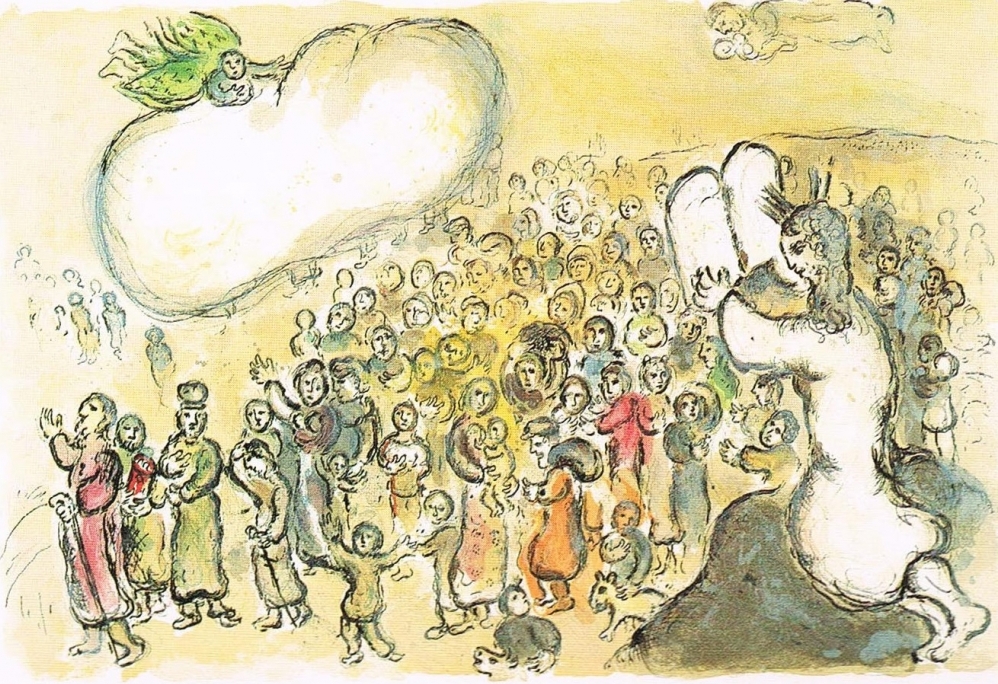

Marc Chagall’s “The Story of Exodus” (1966).

“You Also Were Strangers”

Is the global refugee crisis a Jewish issue? What does the Torah and Jewish history teach us about migrants, refugees, and others?

The earliest biblical story begins with a fall, a forced migration from Eden to unknown lands, and the stories of wandering of peoples have not ceased since.

Abraham, the forefather to the major monotheistic faiths, was a pious man in search of home. He left his home in Ur, modern Iraq, to follow a divine command to find the promised land.

But even before biblical stories and before history, our earliest human ancestors roamed the world, wandering in bands of hunters and gatherers, leaving out of Africa and spreading over the continents of the globe.

The story of humanity is a story of wandering peoples. And the story of the Israelites and the Jews may exemplify this best.

“You shall not oppress a stranger, since you yourselves know the feelings of a stranger, for you also were strangers in the land of Egypt” (Exodus 23:9).

How apt these words seem now, when the news describes refugees being turned away from every border and every country from South America to North America, from Africa to the Middle East, from the Middle East to Europe, from South Asia to East Asia?

Genesis tells us that Jacob’s sons ventured down to Egypt in a time of famine. Things were good until fears of the stranger led to the oppression of the Israelites. The descendants of the hero Joseph escaped Egypt as refugees, wandering in the desert, attacked by others, thirsty and hungry, until with divine sanction, they fought to enter the land of milk and honey.

The Israelite tribes in time gave rise to a famous monarchy, the Davidic kingdom, but it was not fated to last. In 722 BCE, the Assyrian empire conquered the northern kingdom of Israel and deported the tribes living there, leading to the myth of the lost ten tribes.

In 586 BCE, the Babylonians conquered the remaining kingdom of Judah, deporting the elite Jewish community of Jerusalem to Babylon. They were only allowed to return by benevolent Persian rulers seventy years later. Some returned, some remained in Babylonia, supporting the Jewish province from afar.

With the arrival of Alexander the Great’s armies in the region in 333 BCE, Jews enlisted as mercenaries in the famous general’s army, some venturing to Egypt and settling in the new city of Alexandria, and others moving on to other ports in the Mediterranean, including ancient Salonica (Thessaloniki).

Most Jews believe the diaspora began with the Roman destruction of the Temple in 70 CE, but in fact, Jews lived in communities throughout the Mediterranean long before then. And the exigencies of history have driven them to keep moving.

The Arab and Islamic conquest of the Near East liberated Jews from an uneasy existence under the Byzantine Empire. Only the Christian Crusades of the 1100s forced Jews left in Palestine to seek refuge in Egypt. Some of their prayerbooks and their stories have been preserved for us in the Cairo Genizah.

From Egypt, some of those Jews crossed the Mediterranean to Italy and continued North to France, to the region that would become known as Ashkenaz, or west to Spain, to what became known as Sepharad. The Jews gave familiar biblical names to their new homelands.

Alfred Stieglitz’s famous photograph “The Steerage” was taken in 1907.

The Expulsion from Spain drove Jews from Western Europe to Eastern Europe, where they were welcomed warmly by some kingdoms for a time. As in Egypt, success bred resentment and bred persecution.

Within every century and every region, Jews were always on the move, and they weren’t alone. Peoples have always roamed between empires, seeking a peaceful home.

The rise of nation states is a modern and recent development of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, which has given rise to the (wrong) impression that stable borders are natural and inevitable. Borders are not natural or inevitable.

It was the invention of states for nations of people that gave rise to the so-called Jewish problem in the early twentieth century. Where did the Jews belong?

The Holocaust was Nazi Germany’s answer to the Jewish question. And we must not forget that the United States and Great Britain turned away thousands of Jewish refugees fleeing concentration camps and death camps. Boatloads of Jewish refugees almost made it to the shores of Palestine only to be turned away and sent back to certain death.

The refugees from Syria and from Eritrea are now facing a similar fate.

“You shall not oppress a stranger, since you yourselves know the feelings of a stranger, for you also were strangers in the land of Egypt” (Exodus 23:9).

We were also strangers in the land of Europe not so long ago.

Jewish values compel us to think seriously about this issue–both as an international crisis and one that we may unknowingly support with our lifestyles and America’s foreign, economic, and environmental policies.

If we are not advocating for the strangers, we are strengthening their oppressors. And as diaspora Jews especially, we know better and we must do more.

“’The stranger who resides with you shall be to you as the native among you, and you shall love him as yourself, for you were strangers in the land of Egypt; I am the LORD your God’” (Leviticus 19:34).

To Help:

- https://www.hias.org/ (HIAS was originally the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society, now expanded in mission to protect and assist refugees of all faiths and ethnicities)

- https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/europe/5-practical-ways-you-can-help-refugees-trying-to-find-safety-in-europe-10482902.html

- https://www.pri.org/stories/2015-09-03/5-groups-doing-important-work-help-refugees-you-may-not-have-heard

- https://action.sumofus.org/a/help-refugees

Mika Ahuvia is the Althea Stroum Endowed Chair in Jewish Studies and the Marsha and Jay Glazer Endowed Chair in Jewish Studies at the University of Washington. An Israeli-American, Mika was born in Kibbutz Beit Hashita in northern Israel and grew up in Florida. While completing her PhD at Princeton, she researched the formative history of Jewish and Christian communities in the ancient Mediterranean world. Her dissertation, “Israel Among the Angels,” investigates Jewish conceptions of angels in late antiquity.

Mika Ahuvia is the Althea Stroum Endowed Chair in Jewish Studies and the Marsha and Jay Glazer Endowed Chair in Jewish Studies at the University of Washington. An Israeli-American, Mika was born in Kibbutz Beit Hashita in northern Israel and grew up in Florida. While completing her PhD at Princeton, she researched the formative history of Jewish and Christian communities in the ancient Mediterranean world. Her dissertation, “Israel Among the Angels,” investigates Jewish conceptions of angels in late antiquity.

Leave A Comment