Dia de Shabat resivyeron los djudios a ley de la mano de el Dyo,

A sesh de Sivan el mes tresero, ke Yisrael de Mitsrayim salyo.

En anyo de dos mil i kuatrosyentos i kuarenta i ocho, ke el mundo se krio.

On the Sabbath day, the Jews received the Law

On the sixth of Sivan, the third month, when Israel fled from Egypt,

In the year 2448 from the creation of the world.

–La Ketubah de la Ley

On the holiday of Shavuot, Jews commemorate the giving of the Ten Commandments at Mount Sinai by customarily studying Torah long into the night (a practice called velada, meaning to guard or watch, in Ladino) and celebrating the next day with a festive meal of dairy foods. Jews across the world recite the Book of Ruth in synagogues during the afternoon services. Many Sephardic communities precede this reading by singing the famous azharot, a poetical enumeration of the 613 commandments (mitzvoth). Ladino-speaking Jews also included translations of this liturgy and added a unique Ladino song known as La Ketubah de la Ley, the marriage contract of the law, or Torah.

The traditional connection between Shavuot and the Book of Ruth is one of conversion. The events at Sinai were seen as a moment of collective conversion, while the story of Ruth was interpreted as the archetype for an individual proselyte who desired to join the people of Israel. As Ruth said, as indicated in the Ladino translation: ke en lo ke anduvyeres andare, i en lo ke durmyeres durmere, tu puevlo mi puevlo, i tu Dyo mi Dyo. “For wherever you go, I will go; and where you lodge, I will lodge, your people shall be my people and your God my God.”

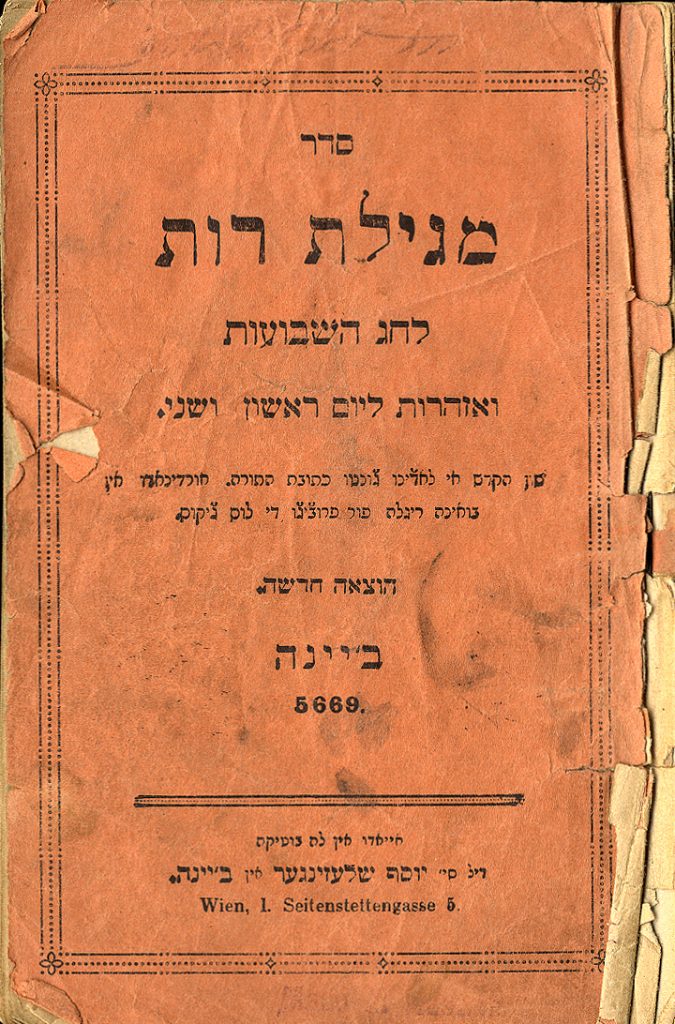

Seder Megilat Rut le-hag ha-Shavuot, courtesy of Elazar Behar.

Much of the Ladino liturgy for the holiday of Shavuot is now available online at the Sephardic Studies Digital Museum. Most notably, we have two copies of Seder Megilat Rut le-hag a-Shavuot: ve-Azharot le-yom rishon ve-sheni. Lashon a-Kodesh i Ladino djunto Ketubat a-Tora. Ordenado en buena regla por provecho de los chikos (The Scroll of Ruth for the festival of Shavuot: and Azharot for the first and second days. [In] the holy tongue [Hebrew] and Ladino together with the marriage contract of the law. Well-ordered for the benefit of children). As the title indicates, this book was published in order to educate children, los chikos.

The well–known Vienna publisher, Joseph Schlesinger, printed this 64-page booklet in 1908/1909. One of the most active publishers of Jewish liturgical texts for consumption by Jews in the Ottoman Empire and beyond, Schlesinger had already published a more extensive collection of Sephardic liturgy for Shavuot twenty years earlier: Bikurim: Minha hadasha kolel seder hag a-Shavu’ot, which includes all of the materials found in his Seder Megilat Rut but also features works appealing to Jews in North Africa such as Sa’adia ben Yosef al-Fayyumi’s Judeo-Arabic translation of the Ten Commandments and another popular version of azharot written by Rabbi Isaac b. Reuven al-Bargeloni.

The Sephardic Studies Program is fortunate to have received four copies in three different colors of the bilingual Hebrew-Ladino Seder Megilat Rut le-hag a-Shavuot. Grace Azose has generously donated one copy that features a soft faded grey cover (UW#858) while Elazar Behar, Gabbai Emeritus of Congregation Ezra Bessaroth, provided us with an identical copy bound together with an orange cover (UW #232).

The Scroll of Ruth for the festival of Shavuot contains both the original Hebrew text and an interlinear Ladino translation. The Hebrew text is printed in meruba (block) script and the Ladino translation in the semi-cursive Hebrew font known as rashi. Both languages include diacritical signs, or nekudot, to help facilitate reading for children and beginners.

Schlesinger’s book also includes a Hebrew text and a Ladino translation of the famous poem azharot, enumerating the 613 commandments found throughout the Torah, by the great medieval Spanish poet and philosopher Solomon Ibn Gabirol (1021-1058). On the first day of Shavuot, the 248 positive commandments are read, and the 365 negative commandments on the second day. (Later codifiers of Jewish law, such as Moses Maimonides, criticized the various versions of azharot, arguing that the task of categorizing the biblical laws should be left to experts in Talmudic jurisprudence rather than poets who may sacrifice legal accuracy for the sake of poetic meter and form.)

Another important Ladino song included in Schlesinger’s booklet is the previously-mentioned Ketubah de la Ley, a famous eighteenth-century kompla (a rhymed Ladino poem) by Rabbi Judah Leon Kalai. The author’s name is spelled out in an acrostic in the verses of this poem, “Ani Yeuda bar Leon Kalai Z”L.” Kalai found inspiration for this kompla in an earlier, similarly titled Hebrew text, Ketubat a-Torah, meaning the marriage contract of the Torah, written by another famous Sephardic poet, the prominent rabbi of Gaza, Israel ben Moshe Nadjara (active 1580-1625). Both songs describe the covenant made at Sinai metaphorically as a marriage made between Israel and the Torah.

The Ladino poem begins (notice the rhymes):

Es razon de alavar a el Dio alto i poderoso,

It is fitting to praise the God of greatness and of might.

Yevo kon eya la ashugar ke trusho de kaza de su padre,

Sheshentos i treje mitsvot para ke se afirmen manyana i tadre,

Para ke el novio las aga, i las guadre.

She carried with her the dowry that she brought from her father’s house,

613 commandments shall be affirmed day and night,

for the groom to fulfill and to keep.

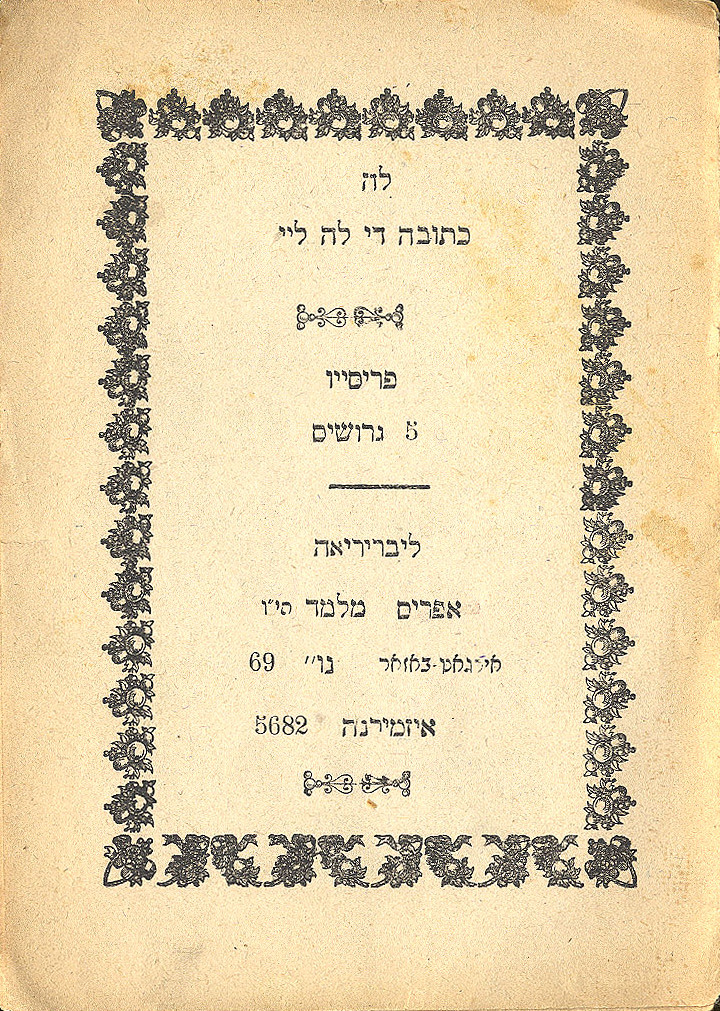

Title page of La Kettubah de la Ley, published in Izmir by Ephraim Melamed. Courtesy of Elazar Behar.

Apparently this poem was so popular that it was even published as a separate booklet. One such example is Ephraim Melamed’s La Ketubah de la Ley, containing only six pages. Printed in Izmir in 1921/1922 (5682) and sold for the modest price of 5 grushim (Turkish kuruş), Melamed’s edition lacks vowels signs. Interestingly, Melamed used the space on the back cover to advertise other valuable items for sale in his library including ritual objects such as tefilin (phylacteries), tallitot de sida (silk prayer shawls) and mezzuzot. Additionally, the Libreria Ephraim Melamed offered school supplies such as ink pens, lead pencils and schoolbooks in Hebrew, Ladino and French. Thanks to Elazar Behar, this little booklet is now online at the Sephardic Studies Digital Library here.

The Book of Ruth, the azharot, and the Ketuba de la Ley provide the key liturgical texts around which Sephardic Jews developed a number of other customs to celebrate Shavuot.

In a recently translated and published Ladino language memoir, the well-known nineteenth century journalist, publisher, and musician Sa’adi Besalel a-Levi describes the scene in Salonika during the last century of the Ottoman Empire (Aron Rodrigue and Sarah Abrevaya Stein, eds., trans. by Isaac Jerusalmi, A Jewish Voice from Ottoman Salonica, The Ladino Memoir of Sa’adi Besalel a-Levi, 6-7):

“My father was an observant Jew…. One Shavu’oth eve, he went after dinner to attend a study session according to the custom of all the Jews when they all went to their synagogues and no one stayed home. That time of the year, nights were shorter, dawn broke early around six thirty, some people would come back home to eat the enchusa, cheese pies, with some rice pudding, sotlach, then go to sleep until 1 or 2 p.m. Others went touring the parks, while lower-class people with wicker baskets filled with cheese pies, rice pudding, raki, and hard-boiled eggs went with their families to parks on the outskirts of the city to eat, get drunk, and fall asleep on the grass. Most of them returned home sick.”

Highlighting the customs in Salonika more than a half-century later, on the eve of World War II, poet Bouena Sarfatty (1916-1997) describes a similar scene of a Salonikan Shavuot (Renée Levine Melammed, An Ode to Salonika, The Ladino Verses of Bouena Sarfatty, 43-44):

Beytsinar eze ouna vouerta grande.

Se kamina kilometros i nounka se ve entera.

Chevouotte debacho el arvole mos asentamos kon la mujer i las kriatouras.

Yivamos Sestos yenos de koumida,

Sin moz oulvidar el sotlatsi i raki Nahmias.

El golf komo Kristal; azemos bagno de mar.

Bevamos a la saloud de Daniel Amar.

Bes Tsinar is a large garden.

One can walk for miles and never see its eternity.

On Shavout we sit under the tree with the wife and the children.

We bring baskets filled with food

Without forgetting the rice pudding dessert and the Nahmias ouzo.

The Gulf [of Salonika] is (clear) like crystal; we take a dip in the sea.

Let us drink to the health of Daniel Amar.

The Salonikan rabbi and historian Michael Molho describes the joyous atmosphere in his native city on Shavuot in his book, Traditions and Customs of the Sephardic Jews of Salonica:

“They would pray and spend the night of the festival in holy readings and songs of joy. They would then arrange to spend some time outside the city, in the middle of green fields under a blue sky. Very early, they would leave the city via one of the gates in the city walls, taking with them a basket full of provisions: cheese pies, hard-boiled eggs, mutton with peas, various salads and above all, the famous sotlach, prepared with goats milk and well-cooked so that the cream pudding takes on a light coffee color and the surface is full of wrinkles like the cheeks of an elderly lady…Naturally there was no shortage of raki.”

Though the customs of the Jews of Salonika tragically came to an end with the Nazi occupation and annihilation of the community, Ladino customs of the holiday live on. Inspired to preserve the memory of those communities destroyed by the Nazis not only in Salonika, but also in Rhodes, descendants of these communities have sought to preserve the spiritual and intellectual accomplishments of their forbearers.

Today, Seattle Sephardic congregations maintain much of the Ladino language of the liturgy for Shavuot. Congregation Ezra Bessaroth’s Hazzan Emeritus Isaac Azose included in his Mahzor Zihron Rahel, according to the Rhodes and Turkish Traditions the entire book of Ruth in English and Hebrew, as well as a transliteration of the Ladino text in Latin characters. In Seattle, both the Ladino and Hebrew verses continue to be read one after the other before the afternoon services preceded by the Ladino poem Ketubah de la Ley.

We are proud to be able to share with the rest of the world two of these very important Hebrew and Ladino texts now available at the Sephardic Studies Digital Library at the University of Washington.

Moadim le-Simha!

[…] Reed more… […]

Ola! Me haber! Ty, vos kero dezir ke me plaze muy muncho De meldar el tu web site. Muy kumplido I enchido d’informacion. Tengo una demand a ke vos kero demandar : ando bushkando kien poueda tener el siduriko ke Se yama : Tefilat kol peh, kon translazion en Djudeo . Yo tengo kopia d’Este siduriko desde la prima odjika fina la numero 138.. por azar, tenesh este livriko? Seria possivle emprimir las kopias ke Me mankan? Oshala Me podash ayoudar. De muevo vos kero kongratular por tu lavoro. Mersi muncho Ty. .!

Ty thank you for this beautiful and informative article….

Hi! Is there a place that I can find the complete Ketuba de la ley in Ladino as well as English? Thank you!

Hi Debby – if you have a query, please email it to sephstud@uw.edu and we will get back to you. Thanks!