This Megillah (scroll) of the book of Esther is from the Ottoman Empire and features a crescent moon ornamentation. Courtesy of Al DeJaen.

Every spring, Jews around the world celebrate the holiday of Purim, which commemorates the victory of the Jewish queen Esther and her uncle Mordechai over the wicked Haman, who attempted to annihilate the Jews of the Persian Empire. As written in the biblical scroll (megillah) of Esther, after Haman is stopped, the Jews rest and rejoice:

“Komo los dias ke olgaron en eyos los djudios de sus enemigos i el mez ke fue boltado a eyos de ansya a alegriya i de limunyo a dia bueno, para azer a eyos dias de kombite i alegria, i enbiamiento de prezentes kada uno a su kompanyero, i dadivas a los dezeozos.”

“The days wherein the Jews had relief from their enemies, and the month which was turned for them from one of sorrow to gladness, and from mourning into a good day: that they should observe them as days of feasting and joy, and for sending gifts to one another and offerings to those in need” (Esther 9:22).

Jewish customs on Purim include listening to the reading of the megillah, eating signature foods, giving charity and gifts to friends, drinking, and making rowdy noise during the reading to blot out the name of Haman (traditionally pronounced Aman among the Sepharadim). We know about some of the traditions and customs of Sephardic Jews in Seattle through items in our collection and personal recollections from first-generation Seattle Sephardim whose families came to the United States from the Ottoman Empire—today’s Turkey and Rhodes—during the early twentieth century.

In a recorded oral history, Elazar Behar fondly recalls a lost custom among the Jews of Rhodes living in Seattle in the 1930s: “A unique custom we had, and that has long been discontinued, but the second night the women would all come to the synagogue in addition to the men. My dad

Platters of Treats

Biscochos are one of the tasty pastries traditionally eaten on Purim.

Behar also recalls the custom of women sending large silver trays of gifts to friends (in the custom mishloach manot) full of biskochos, boulukouniu (sesame with honey), and Hershey’s Kisses. He remembers his mother, Buena Leah Behar, also knitting newborn caps and including one on the tray for a new baby.

“We’d fight which of us kids could take the tray up,” recalls Behar in the interview. “Whenever we deliver the tray, then the woman would give us ten cents or a nickel, which was good money in those days. Kids would be walking up and down the streets early in the evening, Purim evening, and taking these trays back and forth. That’s why we used to fight to take the tray. If I was carrying a tray, my brother would want to go with me because he could get a nickel out of the deal, too.”

Afterwards, they went home to eat borekas and a special dish called huevos de Haman or foulares, a hard-boiled egg wrapped in dough representing Haman in a jail cell.

In his book The Beauty of Sephardic Life, Sam Bension Maimon wrote that after the Megillah the children “used to go to Behor Condioty’s store to buy sweets, such as mavlatches, halva de susam, soujouk, pitas de susam, pitas de kaymak, loucoum, and other candies that only Mr. Condioty knew how to make. All this, so we could go home and greet our families with a hearty ‘Purim alegre y dulce’ (happy and sweet Purim)” (p. 77).*

Another well-known practice on Purim is the custom of drinking alcohol liberally. As the sixteenth century sage Rabbi Joseph Caro indicated in his famous Code of Jewish Law, the Shulhan Aruch, which he composed in the Ottoman city of Safed (present-day Tsfat in Israel): “On Purim a person should drink until he doesn’t know the difference between ‘Cursed be Haman’ and ‘Blessed be Mordechai’” (Orah Hayim, p.695).

And what is a drinking party without drinking songs?

Popular Drinking Ditties for Purim

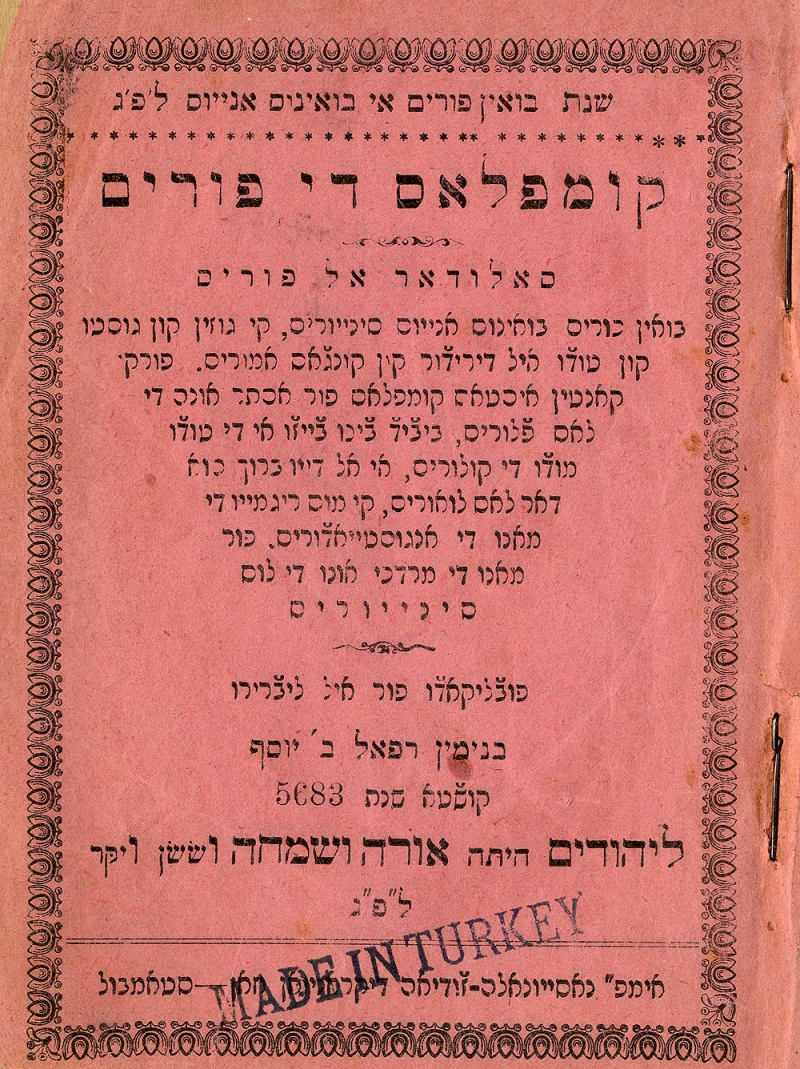

Cover, Komplas de Purim Saludar el Purim. Printed in Istanbul in the Hebrew year 5683 (1922 or 1923). Published by Benjamin Raphael ben Yosef.

Such songs formed part of an extensive corpus of rhymed, Ladino poems known as koplas (or komplas) developed by Sephardic Jews in the Ottoman Empire. Arranged in stanzas, often with refrains, sometimes as acrostics, and intended to be memorized and sung in groups during moments of recreation and celebration, mourning and lamentation, koplas dealt with myriad Jewish themes, including holidays, faith, history, morality, life cycle events, religious practices, folkways, hopes and fears, and politics and satire. Initially composed by rabbis, who sought to make traditional Jewish knowledge more accessible to the Jewish masses in their spoken language, and later by popular authors, koplas served as a foundation of Sephardic Jewish culture for generations.

Perhaps the most famous genre of koplas dealt with the holiday of Purim. Several forgotten drinking songs for Purim are preserved in two books in our Sephardic Studies collection. Notably, several copies of each of the two books have surfaced—a testament to how widespread these koplas once were.

Isaac Azose, Hazzan Emeritus of Congregation Ezra Bessaroth, shared with us Komplas de Purim: Saludar el Purim, printed in Istanbul in the Hebrew year 5683 (1922 or 1923). Published by Benjamin Raphael ben Yosef, one the most prolific printers of religious and secular books in Ladino and Hebrew in the Ottoman Empire during the early twentieth century, Komplas de Purim, with its bright pink cover, introduces readers to its contents in an equally colorful manner:

Saludar al Purim

Buen Purim, buenos anyos sinyores, ke gozen kon gusto

kon todo el deredor kon kondjas amores. Porke

kanten estas komplas por Ester una de

las flores, beved vino viejo i de todo

modo de kolores, i al dio baruh u

dar las loares, ke mos regmio de

mano de angustiadores, por

mano de Mordehai uno de los

sinyores

Purim Greetings

Happy Purim, good year, sirs, may you delight with gusto,

Together with those all around, with flower buds of love.

Sing these komplas for Esther, one of the flowers.

Drink old wine of all varieties, and to God, blessed be He,

give praise, for He redeemed us from

the hands of our persecutors, through

the hand of Mordechai, one of the

men

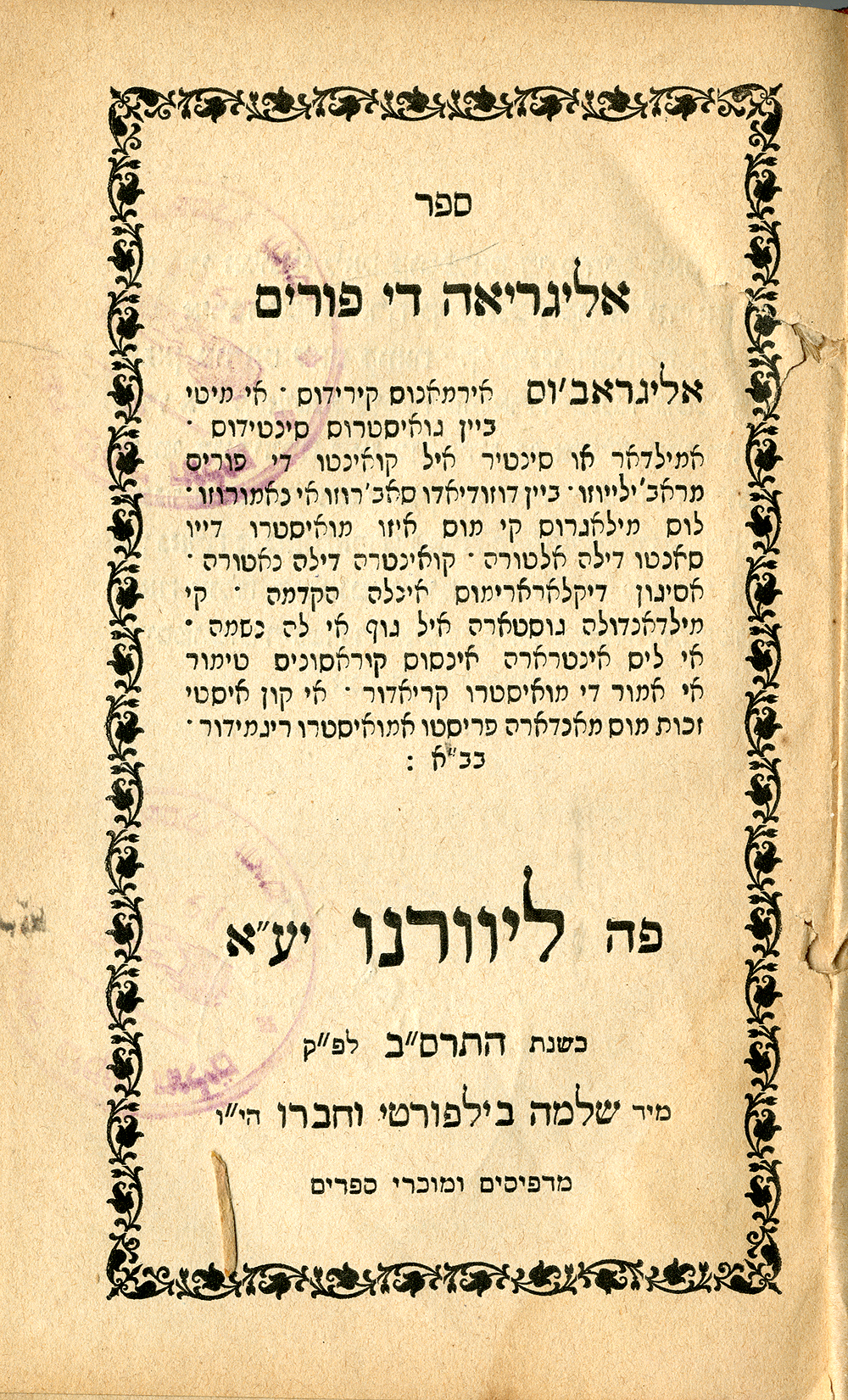

Title page, Sefer Alegria de Purim, published in Livorno in 1902 by Solomon Belforte.

The Sephardic Studies Digital Library also has several copies of Sefer Alegria de Purim, published in Livorno in 1902 by the well-known printing house established in the nineteenth century by Solomon Belforte (1806-1869). That such a book was published in Italy demonstrates that cultural links tied together Sephardic Jews in Italy and the Ottoman Empire during the early twentieth century.

Rabbi Solomon Maimon of Congregation Sephardic Bikur Holim donated one copy of Sefer Alegria de Purim whereas another comes from the library of the late Sam Bension Maimon. An inscription in the latter book reads, “The material, poems, and prose-like compositions here were authored mostly by a certain Ribi Ya’akov Uziel and by Ribi Yom Tov Magula and others.” Uziel and Magula numbered among the most famous composers of koplas in the Ottoman Empire in the eighteenth century and their verses continued to accompany the celebration of Purim into the twentieth century. The full text of both of these songbooks are now available online as part of the Sephardic Studies Digital Library and Museum at the University of Washington.

Here is a little ditty from Alegria de Purim titled “Este Noche de Purim.“ Gladys Pimiento recorded a wonderful rendition of this song also known as “El Testamento de Aman,” available here.

La vizindad adjuntavos,

Beve i enborachavos,

A baylar alevantavos

Ke ansina es el dever.

[Refrain:]

Biva el rey,

Biva yo,

Bivan todos los djudios,

Biva la reyna Esther,

Ke tanto plazer mos dyo

Beve el vino a okas,

Munchos biskochos i roskas,

Ke no esten kedas las bokas,

De komer i de bever.

[Refrain]

No bevesh vino aguado,

Preto, puro i kolorado

i blanko muy alavado

No lo deshesh de bever.

[Refrain]

Los Frankos uzan pedrizes,

Buen tabako de narizes

De afera bilibizes,

Ke es meze para bever

Translation:

Get the neighborhood together,

Drink and get drunk,

Get up to dance,

For thus is our duty.

Refrain:

Long live the king,

Long live I,

Long live all the Jews,

Long live Esther the queen,

That she gave us so much pleasure.

Drink the wine by the gallons,

Many cookies and pastries,

That the mouths should not be still,

From eating and drinking

Don’t drink diluted wine.

Dark, pure and red

And white are praiseworthy.

Don’t stop drinking.

The Europeans make partridges,

Good snuff

To enjoy dried chickpeas,

Which is an appetizer for drinking.

Too Much Noisemaking?

Some rabbinical authorities discourage heavy drinking on the grounds that it is not befitting the Jewish community. Interestingly, in the past another popular custom that continues to this day was highly discouraged: excessive noise making during the megillah reading over Haman’s name. While today children and adults use noisemakers and horns in addition to stomping and pounding, in nineteenth century Rhodes, chief rabbi Rahamim Yeuda Israel condemned the practice. Rabbi Israel tried to put a stop to the ruckus, claiming that it degraded the Divine Presence, stoked enmity with Christian neighbors and the Ottoman government, made a mockery of the Jewish people, violated the commandment of avoiding needless waste, and prevented others from hearing the megillah.

“…on Purim during the reading of the Megilla at night and in the day, when they bang incessantly, as this was the custom in our city for many years to bring slabs and sticks of wood to the synagogue while the children come, each one with his hammer. They practically split the ground with the sound they make during the Megilla reading so that just about a majority of the congregants cannot hear the Megilla reading, as is necessary. Even the adults’ ‘feet run to commit evil’ when they bang with all their might” (from Rabbi Yossi Azose’s translation of Rabbi Israel’s teshuva forbidding the custom of noisemaking, found at this link on the website of Congregation Ezra Bessaroth).

Apparently, Rabbi Israel didn’t win this battle, but Seattle Sephardim don’t cause nearly this much damage — perhaps because they’ve done away with “drinking wine by the gallons”? Whatever the causes for a happy Purim celebration, we wish you:

Buen Purim, buenos anyos

Bueno ke tengamos

Todos los anyos

Happy Purim, good years,

May we have joy

Every year!

* We have done our best to find out what these Turkish candies were. If you know more, please let us know in the comments!

Halva de susam: sesame candy

Loucoum: Turkish Delight (gel, starch, sugar, chopped dates and nuts)

Pitas de susam: sesame in filo

Pitas de kaymak: some type of cream puff? Kaymak means cream, but it may also mean “delicious” or “tasty.” According to Hazzan Isaac Azose, the word pita has nothing to do with pita bread, but rather it’s kind of like a crust, white and hollow inside, in the shape of a round triangle that comes to a point, made with lots of sugar.

Lovely posting, Ty! Congratulations! It’s so informative. Is the Megillah of the Saragossi Purim? We have one in our family and so I was curious. And I’m dying for one of those rozkitas! My aunt Mathilde used to make them to die for!

Happy Purim!

Rina

Great comments. I try to follow what you put on facebook. Thanks for all you do to keep Sephardim going for all the younger generations.

Nice article. One thing though, Sephardic jews do not pronounce Haman as Aman. That is just the result of the modern hebrew Israel accent. I myself as a Sephardic Jew pronounce it Haman as well as everyone I know. There is a He there, you can’t just not pronounce it.

[…] at the Storm Center for Jewish Studies at the University of Washington. It is entitled “Sephardic Purim Customs from the Old World to the Pacific Northwest”. The second is an article from Ynet by Matilda Koen-Sarano with her recollections of Purim. I hope […]

lovely reminds me of my mom.she use to make biskochikos de purim also that pita but it wasn’t sweet it was with KASHKAVAL.

I sure miss Grandma’s biscochos. Also her boyos and bureccas. These days I make do with Trader Joe’s spanakopita, make believe they’re Grandma’s boyos.

This comment is primarily for mc’s comment on February 16th

Dear MC,

I also am a Sepharadi. I was born in Seattle in 1930. At the time I was born, Seattle had a huge population of Sephardic Jews from both Turkey and Rhodes. I’m happy that I was born then, because I was able to grow up listening to all those pioneers, listening to their Ladino, my first language, and listening to them praying in the synagogue. And, as I grew up, I heard them making a beraha and saying ‘Elo’enu Melech A’olam. When I would say a beraha, I would pronounce it exactly as I heard it from my father, alav ashalom, the hazzanim and everyone else. As I grew up, before I became interested in dikduk (grammar), I recognized that there were three letters in the Hebrew alphabet that were not pronounced, other than the nikud that acompanied the letter: the aleph, the ayin and the ‘eh’ (the 5th letter of the Hebrew alphabet). However, as those pioneers passed on, and the children growing up were going to Ashkenazic schools, they were taught that the 5th letter of the Hebrew alphabet was pronounced as an ‘h’, i.e. ‘he’. I was distressed when I kept hearing it pronounced that way, but there was nothing I, personally, could do about it. I could find nothing in writing that could confirm what I had grown up with. That is, until I was given a copy of a book of dikduk, published in Vienna in 1897 by someone by the name of David Moskona. He called his book of dikduk, Magen David. (For your information, Vienna had a huge Ladino-speaking Sephardic community in the 1800’s). After a three page introduction in Ladino in Rashi characters, the very first lessons were: Formas de las ‘A’ (Forms of the sound of ‘Ah’). The letters shown were the Aleph, Ayin and Eh, with the following nekudot (vowels): kamets, patach and sheva patach. Formas de las ‘E’ (Forms of the sound of ‘Eh’). The letters shown were the Aleph, Ayin and Eh, with the following nekudot: tsereh, segol and sheva segol , etc. I think you must get the idea. I finally had something in my hand that substantiated what I had been doing for years.

Moreover, in a 1992 ‘search for my roots’ trip to Turkey, I found a siddur, Sefer Avodat Ashana, that was being used in one of the Istanbul synagogues. In the Table of Contents, they used transliterated Turkish in Roman characters rather than Hebrew. The Table of Contents made reference to the following: Eloai Neshama (not Elohai), Shir Ashirim, Birkat Amazon, Avdala, Allel and Birkat Alevana. I also found a copy of the book that we read at the Pesach seder. It was titled, in English letters, AGADA (not Haggadah). This validated everything I had ever heard, and it validated the book of dikduk I referenced earlier, Magen David. I have published a series of siddurim and mahzorim for our Seattle community, which have been purchased by Turkish and Rhodes communities throughout the U.S. and in South Africa. In all of the series, wherever there is transliterated Hebrew, you will never find the ‘h’ taking the place of the letter ‘eh’. The books were purchased because the communities involved wanted to remain true to the original customs and traditions of the Levantine Sepharadim.

I realize that it is a losing battle, because all of the ‘younger’ members of both synagogues in Seattle, as well as the vast majority of Sephardim like yourself, pronounce the fifth letter of the Hebrew alphabet as ‘He’. If you require proof of what I have written, I will be happy to send you the first few pages of Magen David, The Table of Contents of Siddur Avodat Ashana and the cover page of the Agada from Turkey.

Hazzan Isaac Azose, Seattle (iazose@aol.com)

I have very fond memories of growing up in Portland, OR, in a tight-knit community of Sephardics from Istanbul, Salonika and Rhodos. I adopted Aunty Ogen used to make the best biscochos and soutlach. And the best almond paste dessert! Thanks for the memories, Ty!

My family lived in Jerusalem after leaving turky in 1934. My mother Rebecca used to do all the above mentioned pastries and specially sweet burekitas filled with nuts and dipped in sugar sirop while singing

Purim Purim lanu

Pessah en la Mano

Ya vino enverano

Para yir al campo

We all have such special memories of our Sephardic homes. We cherish them with lot of happiness.

I enjoyed this article very much… loved reading the ladino and the comment regarding Haman’s name which is pronounced Aman. In Castilian the H is silent. You can write Haman but is pronounced Aman

Asi vivas tu largos anios, prezioso artícolo

There is another custom to give the children “purimelik,” which means money, to every child in the family by the adults.

My grandparents on both sides were from Istanbul . I was slways given purimelik as a chilf. I can also remember my grandmother making ‘diblas’ for Purim. It was sweet puff pastry with walnuts, cloves and orange.

Does anyone have the recipe for ‘boyos’.

Such a lovely interesting article. Thank you.

Wonderful article, and tempting photos of the lovely baked goods. Because we are Sephardic on my Dads’ side (marranos in Seville until the 1800s), I chanted my 2 chapters (IV and V) with the Sephardic trope. And because my wife’s family is from Mosul (previously Nineveh), I did it in an Iraqi accent. (בפורים כמו בפורים).

I enjoyed your article very much. I am in search of the Megillat Esther in Ladino in either Hebrew or Latin script. Is such a publication or scan of a publication available for purchase?

Hi, we do have a Ladino-language megillat Esther available in our Sephardic Digital Collection.

You can view it online now: Megilat Ester : im targum ladino be-otiot merubaot