Illustration of a father and son preparing to search for hamets from a Ladino hagada. (ST01235, courtesy Ike Baruch via Ty Alhadeff)

By Makena Mezistrano

Using artifacts from the Sephardic Studies Digital Collection, ‘From the Collection’ introduces the people, places, customs, and ideas that shaped the experiences of Ladino-speaking Sephardic Jews in the Ottoman Empire, the United States, and beyond. Keep up with ‘From the Collection’ by subscribing to the Sephardic Studies Program newsletter.

1930s ad for Albert Levy as editor of La Vara. (ST00691, courtesy Isaac Azose)

Salonican-born Albert Levy is perhaps best known as the editor of La Vara (1922-1948), New York’s longest running Ladino newspaper. His most impactful articles focused on the challenges facing Ladino-speaking Sephardic Jews across the world. But for many in Seattle, Levy is also remembered as a talented Jewish educator: there are still some Sepharadim today who recall classes at the Seattle Sephardic Talmud Torah taught by Levy in the 1930s.

The Jewish holidays were an opportunity for Levy to showcase his pedagogical creativity beyond the classroom on the pages of his paper; throughout the year he crafted special editions of La Vara to get readers in the spirit for upcoming Jewish festivals. These themed issues were capacious in content and style: pieces ran the gamut from scholarly to satirical, literary to poetic, and Levy penned most of the issue himself. Among the most extensive of these festive editions were those for Pesah — the spring holiday of Passover commemorating the Israelites’ Exodus from Egypt.

Levy’s articles in La Vara, and in the many other Ladino periodicals to which he contributed, indicate that he had high hopes for his readers. His writings served to cultivate a Sephardic community that was current with international affairs, educated in Jewish tradition, and composed of upstanding individuals. The holiday editions of his paper were the ideal platform for Levy to deliver all of these educational goals in a digest fit for his contemporary Sephardic audience.

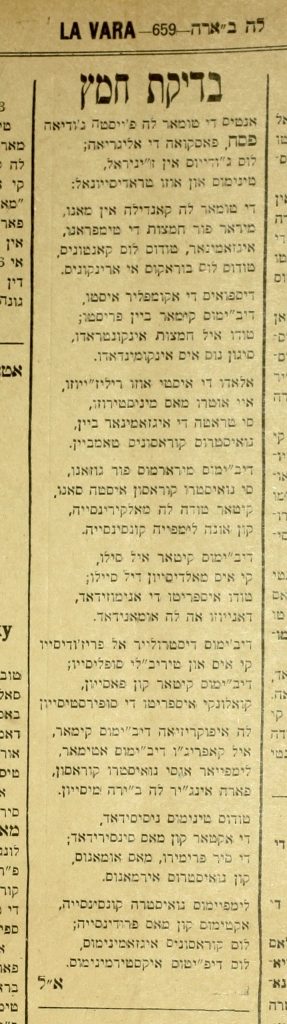

Levy’s Ladino poem from the April 12, 1935 issue of La Vara. (ST01113, courtesy Richard Adatto)

In the April 12, 1935 issue of La Vara — the first of a double feature that year that ran Pesah content — Levy published a poem that exemplifies the ingenuity with which he conveyed Jewish traditions to his readers. Titled “Bedikat Hamets” (literally meaning “checking for leaven”), the ten-verse poem describes the ritual of cleaning one’s home on the night before Passover begins. The poem is also a clear example of Levy’s language ideology: His Ladino is highly Castilianized and devoid of any Turkish- or Greek-origin words — strategies that he deployed in his attempt to “purify” Ladino.

Not only does Jewish law prohibit eating hamets during the week-long Passover holiday, but owning hamets is traditionally forbidden as well. It is thus customary for Jewish people to purge their homes of all leavened products in preparation for Passover.

By the time bedikat hamets takes place, usually within twenty-four hours of the onset of the holiday, homes have already been thoroughly inspected. Families will therefore “plant” hamets throughout the house in order to fulfill the commandment of bedikat hamets. The search is prefaced by a blessing and conducted by candlelight — a scene that Levy portrays in his poem. The ritual culminates the following morning when all the hamets is burned — a process known as bi’ur hamets (literally meaning “burning leaven”) — symbolizing the ultimate elimination of leaven before the holiday.

The majority of Levy’s poem focuses on the symbolic aspect of bedikat hamets. Rabbinic literature equates hamets to the evil inclination (known in Hebrew as the yetser ha-ra) and other harmful character traits, such as haughtiness. Jewish people are not only supposed to be searching their home for leavened products but are also taking a sort of spiritual inventory in order to identify and banish (burn) any undesirable qualities.

Levy’s poem is undoubtedly inspired by this rabbinic teaching: he calls on readers to “destroy prejudice” and “burn hypocrisy,” connecting the physical “spring cleaning” with the spiritual. Though the poem is framed within a Jewish ritual, the message is universal, and Levy employs terminology easily understood by a wide audience. While readers familiar with rabbinic literature would have certainly appreciated Levy’s poem, it was accessible to all. This perfectly illustrates Levy’s ingenuity: “Bedikat Hamets” is just one example of how Levy’s Ladino writings imbued ancient Jewish rituals with contemporary relevance for his Sephardic readers.

| Transliteration:

Antes de tomar la fiesta djudia De tomar la kandela en mano, Despues de akumplir esto, Alado de este uzo relijiozo, Devemos miramos por guzano, Devemos kitar el selo, Devemos destruyir al prejudisio, La ipokrizea devemos kemar, Todos tenemos nesesidad, Limpiamos nuestra konsensia, A”L |

Translation:

Before having the Jewish festival To take a candle in hand, After completing this, Alongside this religious practice, We must carefully inspect, We must remove jealousy, We must destroy prejudice We must burn hypocrisy, All of us have the need, [May] we cleanse our conscience, Albert Levy |

Stay up-to-date with new digital content from the Sephardic Studies Program. Subscribe to our quarterly e-newsletter.

Hi, I was wondering if there is a translation of the transliterated text?

Hi Kathryn – if you viewed the article on your mobile phone then the translation might not have been visible – try on your computer/ipad and it should show up side by side next to the transliteration 🙂

Lindo artículo…muy buen poema…