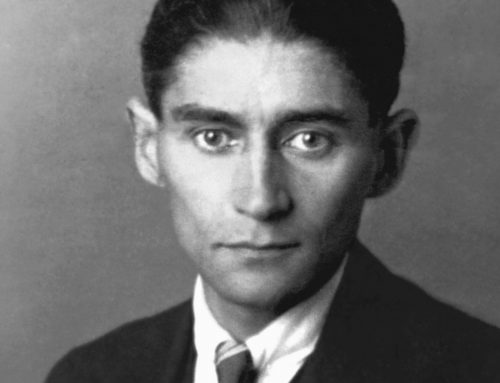

A tale of two Talmud scholars: Uriel Scholnik (Lior Ashkenazi) and Eliezer Scholnik (Shlomo Bar-Aba) in Joseph Cedar’s “Footnote” (2011).

I recently watched the Israeli film “Footnote” (He’arat Shulayim), directed by Joseph Cedar. One of Israel’s prestige movies on the international scene last year, “Footnote” was Israel’s Oscar nominee for the Best Foreign Language Film and was awarded best screenplay at the 2011 Cannes Film Festival. It stars Lior Ashkenazi, whom you might remember as the protagonist of the great post-Holocaust drama “Walk on Water” (Lalekhet Al Hamayim) from a few years back. Playing Professor Uriel Scholnik, Ashkenazi appears as the object of Extreme Makeover: Talmud Scholar. Instead of the leather jacket and designer jeans of a secular Israeli leading man, he sports a yarmulke (skull-cap), beard, and a bit of a paunche. Ok, a serious paunche.

The movie’s plot is a perfect Freudian knot: father and son, engaged in the same academic field but with vastly different levels of success, forever locked in unspoken battles. The elder Scholnik, Eliezer, has worked for decades in relative obscurity. Played with fierce intensity by Shlomo Bar-Aba, he sees himself as the paragon of scholarly purity: one who seeks scientific essence and truth, even if it means settling for an inglorious life of minor discoveries. His son Uriel, on the other hand, has parlayed his research and natural charisma into a career as a public intellectual. A Professor of Talmud at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, Uriel writes popular books about the ancient world and is rewarded by induction into the Israeli Academy of Sciences. The world seems to be his (kosher) oyster.

Cedar’s film has a lot to say–about academia and its sometimes-strange rituals; about parenting and being a child; about the small lives lived in the eternal city of Jerusalem. I recommend viewing the film if only for one brilliant and much commented-upon scene, wherein Uriel faces down a prize selection committee in an impossibly tiny room in the Education Ministry. As a metaphor for the claustrophobic nature of a tiny country wherein everyone is in everyone else’s face all the time, this farcical scene veers towards tragic truth.

However, the point on which I want to focus is the film’s title, which literally translates into “marginal note.” Eliezer’s primary academic achievement, to which he clings with all his might, is his status as the sole living scholar to have been mentioned in a footnote in a foundational work by Talmudic master J.N. Feinstein. This footnote is a point of pride which has turned, in some ways, into Eliezer’s raison d’être. Fueling his pride, his appearance in that long-ago footnote motivates Eliezer to continue his thankless research project, despite having been essentially scooped by a rival scholar years before.

Eliezer’s identity depends upon appearing in someone else’s marginalia; he is defined by being peripherally present in another man’s book. That this book became central to the field of Talmudic scholarship enhances Eliezer’s outsized pride in his footnoted status. Through the twists and turns of the plot, the filmmaker exposes both the ridiculousness and the bitterness of this situation. As viewers, we cringe at Eliezer’s behavior, but at the same time, we are provoked to recall a time when we too might have been overly pleased at the acknowledgment offered by a senior colleague, teacher, or boss. Who among us has not enjoyed being singled out by someone whose respect we desire? Yet Eliezer takes this moment of flattery to its emotional extreme, elevating that long-ago mention into something much more meaningful than Feinstein probably intended.

Cedar’s film got me thinking about the function of footnotes and the role they play in our writing and reading. I recently completed a manuscript with a few hundred footnotes. Some were more perfunctory than others, conveying publication information or basic historical context. Others were labors of love involving translation from foreign languages or philological research, checking into Tanakh (Hebrew bible), concordances, or dictionaries for the semantic history of a Hebrew phrase. Some of these footnotes were mini-essays unto themselves, tracing related topics through multiple authors. The numerical total of footnotes matters less than what they collectively represent: a chorus of gathered materials supporting the arguments I was making in the space above.

Yet my relationship with footnotes has been somewhat fraught. In my early research papers for graduate school, my advisor repeatedly urged me not to bury my opinions in the notes. My papers were well-written, but I tended to highlight other scholars’ work in the body of the discussion while hiding some of my best observations in the margins. Looking back on it, this tendency is understandable: as an apprentice in training mode, I felt it important to demonstrate my grasp of the field rather than trumpet my own arguments.

The resonance with Cedar’s movie is striking. Professor Eliezer Scholnik is content to stay frozen in Feinstein’s footnote like a fly trapped in amber, a fact which (the director suggests) dooms him to a life of drudgery in the darkest corners of the Hebrew University library. I was stuck, too: footnoting myself away from the main action, placing my voice in the margins of my own research.

Part of the process of finding my identity as a scholar has been learning how to acknowledge those who came before me, while exercising authority as an expert in my own right. As those early seminar papers morphed into a dissertation, I gradually shifted the balance. My discussion centered squarely on my arguments, and I marshaled the necessary sources to support me via the footnotes. As the saying goes, we all stand on the shoulders of giants. I had to learn how to let those giants be part of the story I needed to tell, rather than the whole story.

One of the great insights of “Footnote” is that we are negotiating that tricky balance all the time–between being central or marginal, the quoter or the quoted, the teacher or the student, the parent or the child. This theme is going to occupy my thoughts as the new school year, and new Jewish year, get underway.

![Muestros Artistas [Our Artists]: Bringing Sephardic Art and Community Together at the UW](https://jewishstudies.washington.edu/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/UWJS_Muestros-Artistas-cropped-500x383.jpg)

Leave A Comment