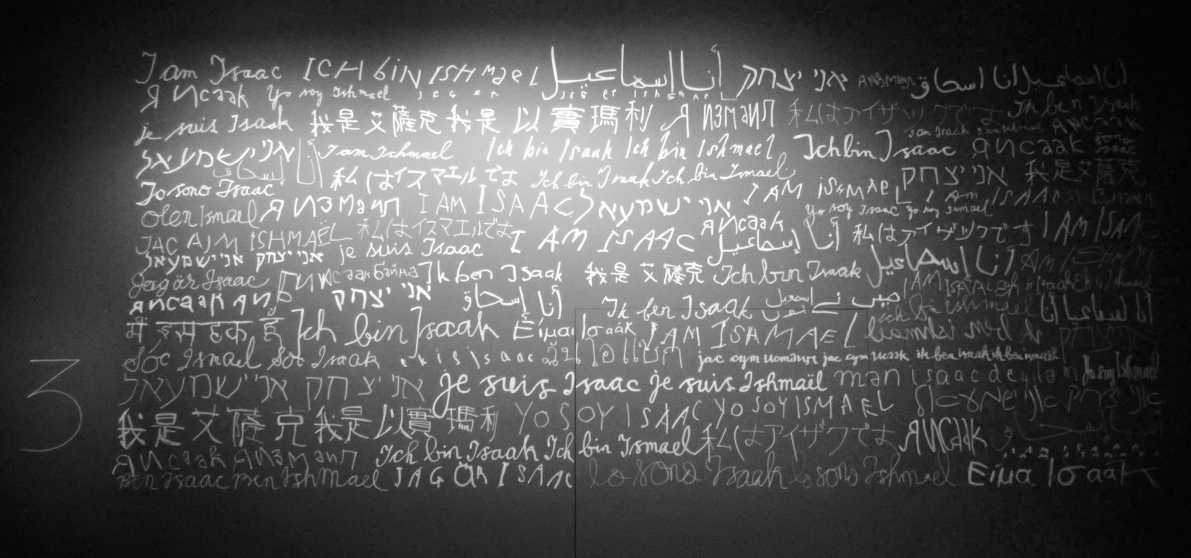

At the “Obedience” exhibit at the Jewish Museum Berlin, this inscribed wall accompanyies the Saskia Boddeke video installation. All photos by Katja Schatte.

Religion, Art, and History

“Some time later God tested Abraham. He said to him, ‘Abraham!’

‘Here I am,’ he replied.

He said, ‘Take your son, your only son Isaac, whom you love, and go the land of Mori’ah, and offer him there as a burnt offering upon on of the mountains of which I shall tell you.’” —Genesis 22:1-2

Saskia Boddeke and Peter Greenaway’s exhibition “Obedience” (“Gehorsam” in German) at the Jewish Museum Berlin does not just come with a poster; it comes with a trailer giving potential visitors a first impression of the multimedia installation. In the Book of Genesis, the initial interaction between Abraham and God leads to the event at the heart of both the biblical narrative and this exhibition, which launched in May and runs through November 15th: Abraham’s obedience.

Abraham’s will to obey eventually suffices as proof of his fear of God; Isaac’s life is saved and a ram sacrificed instead. However, the story of a father’s willingness to sacrifice his son is as drastic as it is central to all three monotheistic world religions—Judaism, Christianity, and Islam (where the story focuses on Ishmael, Abraham’s firstborn son with the slave Hagar). In their exploration of the religious narrative’s contemporary significance, Boddeke and Greenaway want to encourage visitors to go beyond a purely intellectual engagement.

The exhibition is about “feeling first, then thinking,” Greenaway summarizes in an interview for “Aus der jüdischen Welt” (“From the Jewish World”), a Jewish radio program on German public radio. To create this kind of experience, Boddeke and Greenaway have included art from different time periods and of different kinds, including visual, mixed media, film, and sound. The result is an exhibition, which allows visitors to explore the content and significance of the story not only by watching, reading, and listening, but also through touch, smell, and participation.

I was intrigued by the exhibition’s variety of historical, artistic, and religious components and by the intellectual—and emotional—challenges for the visitor. Considering I am a graduate student in history with a keen interest in museum work, this fascination may not come as a surprise. But it was more than that. Even though I am not religious, I believe that religious texts provide important food for thought. They challenge us to consider the historical context in which they were written, while at the same time providing a way of thinking more thoroughly about the challenges of our own time.

Saskia Boddeke and Peter Greenaway’s exhibition presents its visitors with an opportunity for this kind reflection. At the same time, the exhibition is not simply a “tool” for visitors to explore their own realities. A wide variety of additional and mostly free events surrounding the exhibition allow visitors from different walks of life to engage with the story of Abraham and Isaac/Ishmael from a religious, artistic, and art historical perspective.

15 Rooms and Several Perspectives on Abraham

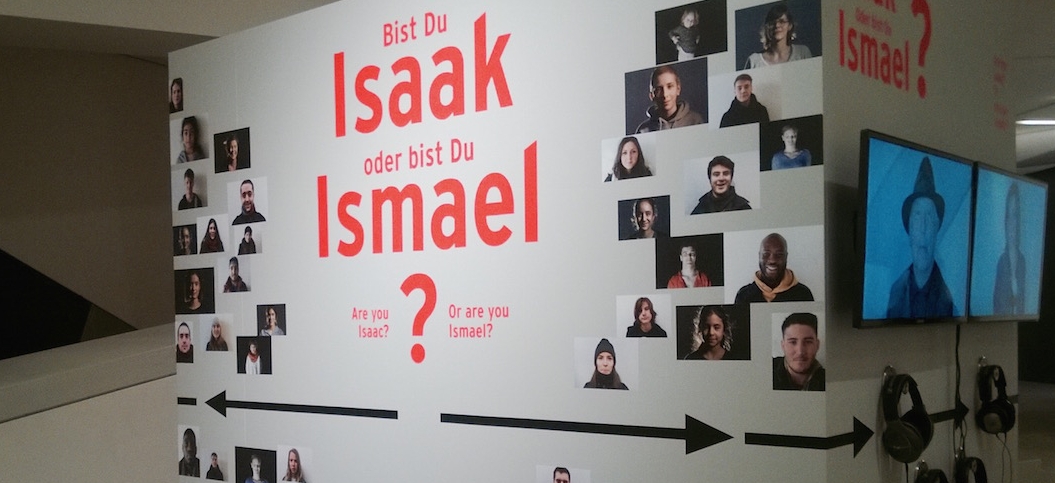

“Obedience” consists of fifteen rooms. In line with the artists’ goal to engage visitors on a personal level, it begins and ends with the question of identification: Are you Isaac or Ishmael? Or are you Abraham? What does it mean to be either? Between these two choices, there is the exhibition. As they make their way through it, visitors see historical documents, some artwork specifically produced for the exhibition, including another film by Saskia Boddeke, and many examples of artistic engagement with the biblical story over the centuries.

It takes work, on the part of the viewer, to understand the ways in which Boddeke, Greenaway, and the featured artists associate the story of Abraham and Isaac/Ishmael with issues of their own times. And because the artwork on display is so varied in its period of origin, medium, and perspective, visitors are constantly being challenged to engage and reflect.

In the videos at this station, participants explain in their native languages whether they are Isaac or Ishmael.

Upon entering the exhibition and reading God’s call upon Abraham, visitors hear the voice of Isaac/Ishmael from the mouths of young people in the next room. In a video installation by Saskia Boddeke, children, teenagers, and young adults from different parts of the world proclaim “I’m Isaac” or “I’m Ishmael” in their native language. For her installation, Boddeke sent out a video call for participation prior to the inauguration of the exhibition, asking young people to record themselves. In the video message she writes:

Do you feel you are an Isaac or an Ishmael?

That you have the right to be protected!

That you deserve a future in a world without wars!

In the religious narratives, Isaac/Ishmael survives, as visitors are reminded in the three rooms dedicated to religious interpretations in Islam, Christianity, and Judaism. Room number nine is dedicated to Judaism and explores the Akedah (as the near-sacrifice of Isaac is known in Hebrew). Visitors hear a child’s voice reading from the 613 commandments and see a scene from Boddeke’s film in which Sarah proclaims that it will be up to God to save Isaac. Along the walls, visitors can find historical Jewish objects and texts. The ninth room of the exhibition thus becomes in itself an example of the interdisciplinary approach of the entire exhibition, bringing together religious, historical, and artistic elements.

It is precisely this blending of perspectives which brings visitors back to the challenges of our own time as they approach the end of the exhibition. Room fourteen focuses on the sacrifice of the ram. Kyu Seok Oh’s sober installation “Sheep” stands in stark contrast to the documentary scenes on three big screens on the opposite wall. We see children fleeing from war. We hear them talk about difficult, often traumatic experiences of violence, trying to make sense of them as they speak. As I explored the exhibit, it was impossible not to think of the hostility many refugees, just like the children in the film snippets, are experiencing in Germany and Europe: xenophobic protesters chanting “foreigners out” in Dresden, violent attacks on refugees and their accommodations across Germany, a Hungarian journalist tripping and kicking refugees running from a holding camp. These are only some examples of what has been dubbed the “refugee crisis” over the past months, but really seems to be a crisis of humanity.

In the biblical narrative, God is merciful. But are we?

Are You Abraham?

This is precisely the question the artists leave visitors with as they proceed to the final room. Its walls are plastered with newspaper articles in many languages, across them written in large red letters a question: Are you Abraham? Or, as Saskia Boddeke put it in an interview for Blogerim, the official blog of the Jewish Museum: “We sacrifice our youth to have peace and that is what our exhibition is about. The question of obedience to God and his will becomes a question of obedience to society, to the pressure of society to maintain what we have. (…) Would you sacrifice your child? How do you behave when children of others are sacrificed?”

The newspaper articles that fill the walls of the final room remind their readers that the significance of those questions goes beyond moments of local crisis when it becomes impossible to ignore that we are ourselves implicated. The articles cover issues such as the Charlie Hebdo attack, the Greek debt crisis, and French military members’ struggle to be compensated for health damages they suffered while participating in nuclear testing. Visitors may have heard of some or many of the issues covered in the newspaper articles. Depending on the number of languages they speak, they may find coverage of the same event from different perspectives. But there is one perspective that the exhibition adds to the visitor’s reception of all of them: a reminder that all of these stories are about more than politics or ideology; they are about human lives.

An emotionally moving section of the exhibit explores the bond between mothers and children by focusing on the biblical Sarah and Hagar.

What may sound like a trivial observation gains renewed urgency when we bring the German context back in. Current outbursts of xenophobic rhetoric and violent racism do not come out of nowhere; they were preceded by decades of anti-immigrant sentiments and prejudice in both Germanys. And, in recent years, the growing desire on the part of many Germans to draw a “finish line” under German society’s engagement with the Holocaust has further complicated the situation. In Stranger in My Own Country, historian and political scientist Yasha Mounk writes about growing up Jewish in post-reunification Germany and how this experience relates to anti-immigration sentiments: “For all the fashionable rhetoric of including Jews the better to exclude Turks, in reality the current rebellion against pluralism is disastrous for us all.” In this context, Boddeke and Greenaway’s plea to look for our shared humanity seems timelier than ever.

It is certainly not a new plea. But drawing on art, history, and religion in the multi-facetted ways the exhibition does, gives it a new kind of potential to initiate reflection and conversations. What is more, “Obedience” demonstrates that it is possible to create a space featuring all these elements without expecting visitors to have profound background knowledge of any of them. Sensory and interactive features as well as feeling confused and leaving the exhibition with more questions than answer—these are all part of the experience. Emotions and intellect exist side by side.

Thus, when everything has been said, written, and argued, art exhibitions have the potential to provide a space to reflect, revise one’s points of view, and explore ideas free from the pressure to draw final conclusions. They can turn gridlocks into starting points. “Obedience” is a successful example of such a space.

Links for Further Exploration

- Broken Glass and the Berlin Wall by Katja Schatte (Dec. 2, 2014)

- Announcing the 2015-16 Jewish Studies Graduate Fellows! (June 9, 2015)

![Muestros Artistas [Our Artists]: Bringing Sephardic Art and Community Together at the UW](https://jewishstudies.washington.edu/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/UWJS_Muestros-Artistas-cropped-500x383.jpg)