Photo Credit: Garzon

By Denise Grollmus

Type “death of the humanities” into Google and you get a long list of dreary titles: “The Morbid Fascination with the Death of the Humanities” from The Atlantic, “On The Slow Death of the Humanities” from Counterpunch, “The Liberal Arts Are Dead; Long Live STEM” from The Federalist.

It’s no secret that humanities scholars have spent the past few decades forced to justify their value, particularly in the face of significant funding cuts to higher education. The problem is that the humanistic value they offer is incredibly difficult to quantify, though researchers have tried.

In an age where big data and calculable returns on investment have become privileged forms of information, the humanities have found themselves on the wrong side of the contemporary values continuum—even if data means very little without the necessary tools of analysis and critical thinking that the humanities provide and sharpen.

But that was all before the Age of Trump. Which is not to say that the humanities have suddenly found themselves flush with funding. Of course, Trump and his Secretary of Education plan to do just the opposite. Not even STEM appears to be safe. However, the Trump administration’s attack on public education rings differently from the previously steady stream of budget slashes that have plagued the American education system.

Not only is resistance to this administration’s policies some of the fiercest we’ve seen in American history, but, in many ways, the rise of Trump speaks both to what happens when a nation devalues education—especially the teaching of critical reading practices—and to the increasing public demand for the expertise that the humanities produce. In many ways, Trump has made higher education—particularly the humanities and social sciences—valuable again.

Take the case of Jewish Studies. Ever since the election, Jewish Studies scholars have found themselves increasingly called upon by major media outlets to weigh in on everything from the rise of Trump and the dramatic increase in anti-Semitic incidents to the ascent of ethnonationalism and racial hatred across the West.

Less than a week after Trump’s election, more than 240 Jewish Studies scholars specializing in Holocaust history signed a public statement condemning Trump’s hateful and inflammatory threats against minorities. The statement, originally published in Jewish Journal, went viral. Two months later, Jewish Studies scholars once again made headlines when they sent a letter, signed by over 200 academics, to Congress, urging members to block Trump’s Muslim Ban. And if anyone hadn’t heard of Timothy Snyder before Trump’s election, then they surely knew his name after his Facebook post, “Twenty ways to recognize tyranny—and fight it,” went viral in November and led to the publication of his most recent book, On Tyranny: Twenty Lessons from the Twentieth Century, which became a #1 New York Times bestseller.

Even Hannah Arendt is enjoying a sudden spike in sales. Her formidable 500-page tome of dense political philosophy, The Origins of Totalitarianism, has been selling sixteen times its average rate since the election.

If it was unclear what good the humanities and social sciences served before the Age of Trump, it has become abundantly clear how eager the public is for the knowledge that these fields produce, and how important the university’s role is in serving that public interest. As David Myers, a professor of Jewish History at UCLA, wrote in Jewish Journal just a month after the election, “The university, in particular, must become a key site of vigilance, resistance and critical thinking in American civil society in the age of Trump. This is not a violation of its historic function but consistent with the Humboldtian ideal of the university as an institution in the service of society. Not as a tool of the state, but in the service of society at large!”

It was with that spirit that Zoë Roth (Durham University) and Jonathan Freedman (University of Michigan—Ann Arbor)—both literary scholars and critics who work in the field of Jewish Studies—organized a two-day symposium at the University of London entitled “World Literatures and the New Totalitarianism.” They invited eleven literary scholars and critics, and one historian, to give papers that would consider how literature has responded to—and can help us think through—the political move to the far right not only in the US, but in the UK, mainland Europe, and the postcolonial world as well.

Of the many questions and concerns raised in their call for papers, the organizers asked, “What is the role of the humanities in resisting totalizing forces?” What is particularly compelling about this question is how it reflects a dramatic shift in the conversation about the socio-political role of literary scholars and critics. No longer were we asking whether we should have a larger social role or whether we, in fact, did. In the new political era, there is no doubt that those of us who teach people how to read and think critically about the act of reading and interpretation should explicitly consider the social and political implications of our work beyond the ivory tower.

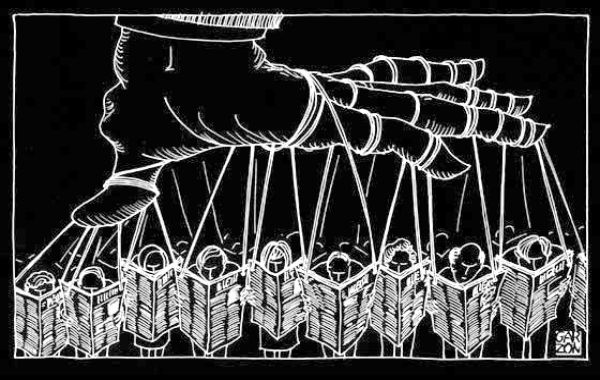

For one thing, the speed at which the new political paradigm assaults our senses with troubling breaking news disallows the old model of trickle down intellectualism. In fact, speed, itself, became one of the many themes to emerge across the variety of papers that were delivered on May 15 and 16 in London. Whether it was the alacrity with which the Trump administration was purging the government of anyone who—and any norms that—stood in its way or the pace and breadth with which fake news is now effectively propagated through social media, everyone concurred that one of the greatest challenges posed for resistance was what Arendt refers to in The Origins of Totalitarianism as “the perpetual motion mania of totalitarian movements which can remain in power only so long as they keep moving and set everything in motion.”

Many of us commented that we found ourselves continually updating our papers to reflect the most current political situation—whether it was revising references to James Comey as the “former” director of the FBI, or deleting closing questions about how the future might unfold—questions that were often swiftly and violently answered by yet another breaking news alert (hint: the answers given were often beyond our wildest imaginations).

It was a surreal experience for a group of people who tend to write and think over very long periods of time about objects which, materially, don’t change all that much, or, at least, aren’t completely transformed by one breaking news alert. In many ways, it seemed as though literary analysis may be an impractical, inefficient tool to respond to the swiftness of the current political moment.

However, in her paper, “Forms of Totalitarianism and the Totality of Form: Arendt, Aesthetics, and the State of Emergency,” Zoë Roth suggested that, in fact, the plodding process of literary criticism is exactly what we need to launch an effective resistance against the acceleration of totalitarian forms. Roth began her paper by first unpacking the formal qualities of totalitarianism through a reading of Arendt that pointed to the ways in which we could understand our current political situation—one which emerged rapidly and, for some, shockingly, and has made the world incoherent in the way that it inverts established logics, largely through a never-ending discourse of lies.

The problem with resisting this political form, Professor Roth contends, is that we become complicit in it vis-à-vis its temporality when we respond to it as the state of emergency. One of the ways we can resist reproducing the swiftness of totalitarian forms is by stepping outside the state of emergency. For example, the most effective resistance against Trump thus far has, in many ways, been the crawling pace at which the liberal institutions that Trump seeks to destroy (but also needs in order to destroy them) tend to move.

But also, it’s critical that we, in the public sphere, disallow the speed of the Twitter-driven news cycle from keeping us in a state of crisis, as well. Part of this, Roth argues, can be done through the critical engagement with art that the humanities cultivates and fosters and can be used to build political communities capable of robust resistance. That is, our resistance to Trump and the larger far right political forces throughout the West must be informed not by a resistance to the content of their politics, but to their form, including their temporalities.

In my own paper, “Illiberal Readers and the Crisis of Free Speech: Blood Libel, Pizzagate, and the Rise of Ethnonationalism,” I also considered the role that speed has played in the rise of the far right, particularly through the incredible rate at which fake news, such as Pizzagate, is disseminated and reinforced online.

Not only did I consider the ways in which this speed makes engaging in critical reading practices incredibly difficult for even the most astute readers, but I also examined the ways in which the rapid spread of such information itself instigates extreme physical violence. Part of my examination looked at the ways in which the explosion of print culture and the popular press at the turn of the 19th century encouraged the reemergence and juridico-scientific rearticulation of the blood libel myth throughout Europe, as well as how this reemergence ultimately led to hundreds of pogroms even after World War II.

Part of my argument was that similar discourses of lies and hate currently being circulated against minorities cannot be protected by liberal free speech laws when those very laws are predicated on the public’s ability to critically read and interpret texts. Without the cultivation and implementation of those reading practices and in the face of the speed at which misinformation is being spread, history shows us that the only logical outcome of uncritical engagement with such information is extreme physical violence.

But deceleration wasn’t the only tool that we, as literary scholars, critics and pedagogues, felt our field could provide in the resistance to totalizing forces. Nasia Anam (Princeton University), Max Silverstein (University of Leeds), and Sasha Senderovich (who will be joining UW’s Jewish Studies program this fall) offered wildly different papers with complementary messages in regard to the ways in which both literary fiction and film can provide important moments of defamiliarization through which we are encouraged to read our reality in ways that crucially challenge those very assumptions that make resistance so difficult.

For example, Silverman’s paper offered a reading of Chantal Akerman’s 1975 film Jeanne Dielman, 23, quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles as an example of what he calls “concentrationary art,” a movement amongst post-war French filmmakers that Silverman argues sought to create representations of everyday life that would bear out the ways in which life in Nazi concentration camps—particularly the transit camps that existed in France, rather than the death camps in Poland—did not end with the war, but continued on in modern urban life, particularly in post-war modern housing estates, of which we can understand concentration camps as the most intense form.

By defamiliarizing everyday life in order to draw attention to its “concentrationariness,” the viewer engages in the visual experience of what Arendt would describe as the banality of evil, or rather, the way in which we can understand the fundamental ordinariness that played such a crucial role in the ability of Nazi Germany to carry out the Holocaust, as well as the ways in which that ordinariness is capable of masking the extraordinary violence that continues to plague our world.

Though concentrationary art and the eerie applicability of Arendt to our current moment don’t seem immediately inspiring or uplifting, after two days of listening to the ways in which such a wide range of literary scholars are thinking about how their work can inform resistance and how we, as teachers of reading and writing, can help people make better sense of the world in which they live, I have had a wealth to think about and try to implement in my own teaching and scholarship.

I am grateful to the Stroum Center for providing me with the support so that I could take part in this symposium. It reminded me how important the work that we do at the intersection of literary studies and Jewish Studies is, especially in these strange and scary times.

Denise Grollmus is a Ph.D. candidate in the English Department at the University of Washington. She is currently working on her dissertation, which examines the ways in which narratives of addiction employ religious and spiritual discourses to complicate medical models of addiction as well as normative understandings about self-control and self-governance. Denise was also a Stroum Studies Graduate Student Fellow in 2013-14. She has also served as assistant director in UW’s Expository Writing Program.

Denise Grollmus is a Ph.D. candidate in the English Department at the University of Washington. She is currently working on her dissertation, which examines the ways in which narratives of addiction employ religious and spiritual discourses to complicate medical models of addiction as well as normative understandings about self-control and self-governance. Denise was also a Stroum Studies Graduate Student Fellow in 2013-14. She has also served as assistant director in UW’s Expository Writing Program.

For Further Exploration

- Read Denise Grollmus’s interview with author Dana Horn

- Read an interview with Philosophy professor Michael Rosenthal, “Why do Hannah Arendt’s Ideas about Evil and the Holocaust Still Matter?“

- Learn more about Stroum Center Opportunity Grants

- Learn more about the Graduate Fellowship at the Stroum Center for Jewish Studies

- Read more online articles written by Stroum Center Graduate Fellows

![Muestros Artistas [Our Artists]: Bringing Sephardic Art and Community Together at the UW](https://jewishstudies.washington.edu/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/UWJS_Muestros-Artistas-cropped-500x383.jpg)