Why did the Baruchs and friends play Turkish records?

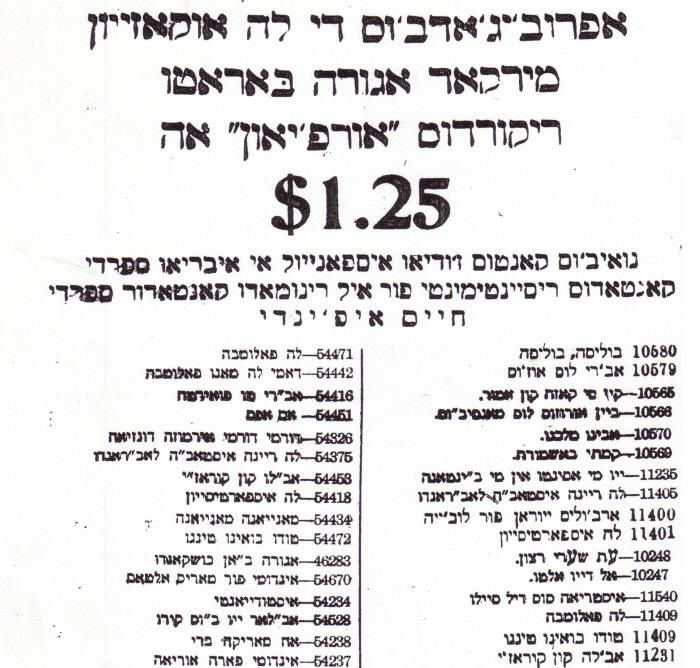

Advertisement from the New York Ladino newspaper La Amerika (November 3, 1922). The ad features popular Ladino songs such as Dame la mano palomba (“Give me your hand, dove”) and the lullaby Durme durme (“Sleep, sleep”). Source: Collection of Joel Bresler, sephardicmusic.org.

Sam and Dona Baruchs’ records feature mostly Turkish songs. Renowned twentieth century Turkish singer, Safiye Ayla, for example, sings “Saatlerce Baş Başa” (Together for Hours). A Turkish contemporary of hers, Mahmure Şenses, sings “Usandım Erkeklerden” (I’m Sick of Men), and Mary Vartanian, an Ottoman-Armenian immigrant to New York City, offers up “Elmas Yüzük Parmakta” (A Diamond Ring on the Finger). Out of ten 2-sided records only one is in Ladino – “Mis Penserios Gazel” (My Thoughts) and “Un Anio Ay” (It’s Been a Year) by the Ottoman-Jewish immigrant to New York City, the vocalist and oud player, Victoria Hazan.

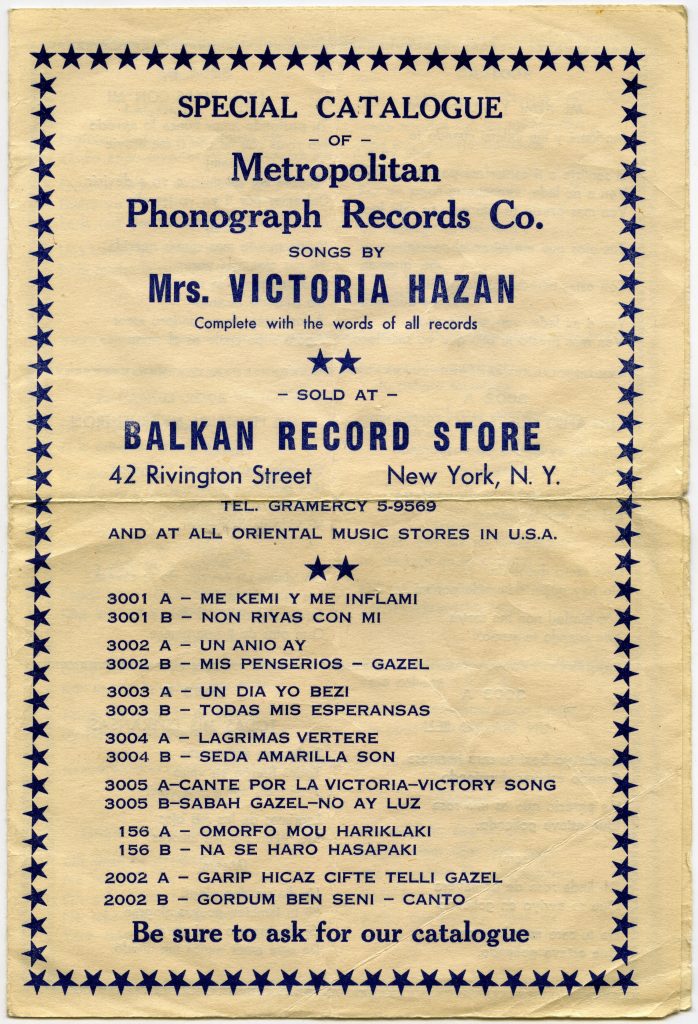

Why so many Turkish language tunes? Why not more Ladino songs, given that many Ottoman Jewish singers like Isak Algazi and Haim Efendi, recording in the late Ottoman empire and early Turkish Republic, produced Ladino song records? Immigrant singers like Victoria Hazan also recorded in Ladino (as well as in Turkish and Greek) in the 1940s. And Ladino newspapers like La Vara and La Amerika ran ads listing Ladino and Hebrew songs on offer from various record labels and singers.

Our question extends beyond Seattle: In other regions of the United States researchers and collectors observe similar purchasing patterns to those of the Baruchs. Turkish songs dominate most record collections of first generation Sephardic immigrants, echoing the popularity of Turkish music performed in homes, cafés, music halls, and streets on both sides of the Atlantic in the first decades of the twentieth century.

1942 catalog of Ladino and Turkish songs by Victoria Hazan sold on New York’s Lower East Side (ST01396, courtesy Estelle Ovadia).

To be sure, Ottoman and Turkish Jewry fully engaged with their urban musical cultures as seen in their neighborly and artistic relationships, instrumental arrangements, vocal style, and performance practices across multiple genres. First generation immigrant Ladino speakers, moreover, often had a working knowledge of Turkish and/or Greek – and sometimes other tongues of their region as well as French, the language of an Alliance Israélite Universelle education at schools for Jews around the Mediterranean and Middle East. It’s not surprising, then, that in addition to their extensive Ladino song repertoire, Turkish Jews in Seattle sang and owned records of popular Turkish and sometimes Greek music.

According to 78 rpm collectors, however, first generation record collections of primarily Ladino songs are anomalies. Why not also own recordings of Ladino singers and songs, as beloved and as performed, if not more so, in the community?

A clue lies in how 78 rpm records were used. Recalling their childhoods in Seattle during the 1930s and 1940s, several Sephardic community members remember house parties (nochadas) after Shabbat on Saturday nights. Sitting in the corner of a living room, they watched their parents and neighbors dance in the Turkish style: bailar a la Turka.

“All the relatives would go,” one individual recollects. “Women and men mixed together. They did circle dancing and put money on their foreheads.”

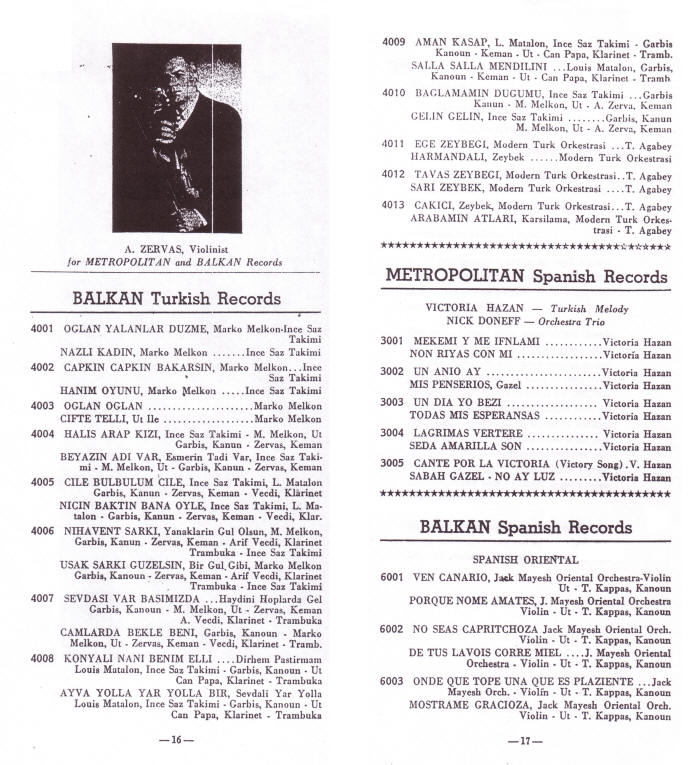

Undated catalogue of Balkan and Metropolitan records, c. 1948. Victoria Hazan

recorded with violinist Athanasios Zervas as well as fellow Ottoman immigrant

musicians to New York City. Collection of Joel Bresler, sephardicmusic.org

Isaac Azose, hazzan (cantor) emeritus of Congregation Ezra Bessaroth whose parents Jack and Louise loved to sing, remembers the modest dance floor of a couple’s living room, only big enough for two or three people at a time. “They would dance together — sometimes two men, sometimes a man and a woman — snapping their fingers, shaking their shoulders.”

Turkish song “Yandım Tokat Yandım” (“I’m burned Tokat I’m burned”), sung by Mary Vartanian in the pan-Middle Eastern çiftetelli rythym (ST01381, courtesy Isaac and Rachel Baruch via Ty Alhadeff).

The host served refreshments like rakı (anise liquor), coffee, and biskotti. “People enjoyed themselves to no end,” another recounts. “If they had problems, they left them outside.”

This is when people played records, according to these children of immigrants. The pleasures of socializing were enlivened by the soundtrack of popular Turkish music. The dancing echoes Greek horas and dances to Mideast rhythms by individuals or couples. The practice of offering money to dancers (pintar) honors them in a way that recalls customary audience appreciation of professional Middle Eastern dancers.

The record player was kept busy on other celebratory occasions as well, where Turkish records accompanied, for example, every stage of the engagement process – frequent occasions, especially after World War II. “Engagement parties were very noisy and energetic,” reflects a guest. “The doors were left open. I’m surprised the neighbors didn’t complain!”

Indeed, among the nine Turkish records in the Baruchs’ collection, at least six songs have dance rhythms, including çiftetelli (pronounced “chiftetelli”), ubiquitous across the Mediterranean, Mideast, and Central Asian regions and wedded to the shoulder-shaking shimmying that Isaac recalls.

Among first generation Seattle Sepharadim, then, popular Turkish records functioned as danceable party music in homes where record players were at the ready to amplify the music and provide the beat. “They worked up a sweat,” the engagement party guest continues, “There was a lot of pounding and stomping. They had rhythm.”