By Ty Alhadeff

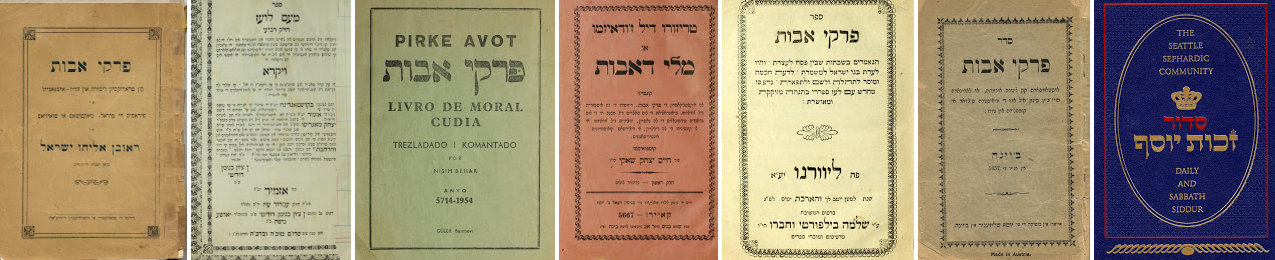

Ladino translations of Pirke Avot from the Sephardic Studies Library at the University of Washington

Si non yo para mi, ken para mi, i kuando yo para mi, mizmo ke yo – i si non agora, kuando?

If I am not for myself, who is for me? And when I am for myself, what am I? And if not now, when?

Se azyen orasyon por la pas de el reyno, ke si non por la temor, kada uno a su kompanyero, bivo se lo englutyera.

Pray for the peace of the government, for were it not for the fear

Non en muestras manos en pas de los malos, i tambyen non de kastigeryo de los djustos.

It is not in our hands that the wicked should be at peace nor that the just should be punished.

Se akonantán en pas de todo ombre, i se koda a los leones, i non seas kavesa a los rapozos.

Be the first to greet everyone, be the tail of lions, and do not be the head of foxes.

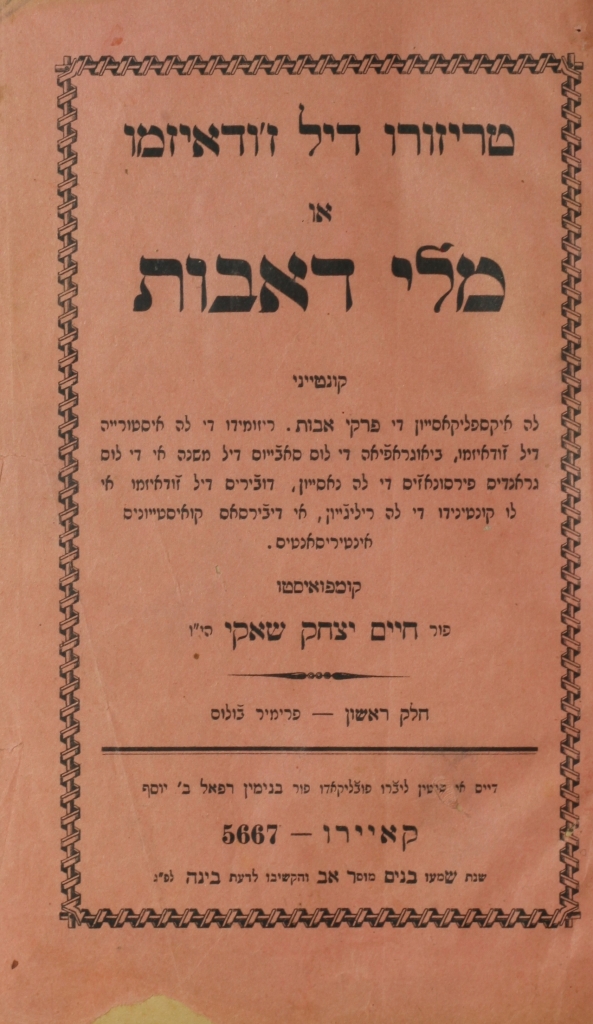

Rabbi Haim Shaki’s Trezoro de Djudaizmo (Treasure of Judaism) published in Cairo, 1907. The first part of the book focuses on an “la eksplikasion de Pirke Avot” (explication of Pirke Avot, a translation and interpretation of this classic text) (From the library of Albert Adatto; courtesy of his son, Richard Adatto)

These popular Ladino sayings come from an ancient collection of Jewish teachings known as Pirke Avot, one of the most popular rabbinic compositions of all time that gained a special place in Sephardic tradition. Based on sections of the Mishna, the first major compilation of Jewish oral tradition, Pirke Avot includes mottos of the leading rabbis of antiquity that emphasize profound yet concise ideas about God and humanity, good and evil, reward and punishment, love and hate, law and anarchy. The accessible language and universal themes of these ethical maxims have resonated with Jews across the generations and resulted in their inclusion in standard prayer books and their translation into many languages—including more than fifty separate editions in Ladino alone!

Sephardic Jews carried the messages of Pirke Avot from Spain to the Ottoman Empire right here to our doorsteps in Seattle. The Sephardic Studies Digital Library at the University of Washington includes eight editions—including several never before documented—that demonstrate the centrality of Pirke Avot to Sephardic tradition that continues into the twenty-first century.

La Vara newspaper advertisement for a Vienna edition of Pirke Avot in Ladino, May 1, 1931.

The inclusion of Pirke Avot in Jewish liturgy and study has a long history. During the Geonic era (600 to 1000 CE), Babylonian Jews developed the tradition of chanting Pirke Avot on the Sabbaths between the holidays of Passover and Shavuot. Sephardic synagogues maintain the custom today. Commentators explain that the custom of studying Pirke Avot during the spring stems from a recognition that the season brings with it increased socialization that may entice people to stray from moral behavior. The “ethics of our fathers” therefore guides the faithful back to the proper path, especially in anticipation of the holiday of Shavuot, which celebrates God giving the Torah to the Jewish people.

The importance of Pirke Avot led Maimonides and many other Sephardic rabbis to compose commentaries on the text over the generations. The famous Isaac Abravanel (Abarbanel), who served as the financier to Queen Isabella at the time of expulsion from Spain in 1492, composed his own commentary on Pirke Avot that was published in Istanbul, the capital of the Ottoman Empire, in 1505. Scholars suggest that the expulsion from Spain inspired rabbis to write more ethical texts, including commentaries on Pirke Avot, than ever before as a way to cope with the trauma of dislocation and to ensure that Sephardic Jews found comfort, consolation, and direction in the ancient teachings of the sages.

From 1553 to 2002, over fifty different translations of Pirke Avot into Ladino were published in eighteen different locations across the Sephardic world: the first in Ferrara, Italy, and more recently, right here in Seattle, Washington. According to a study by Israeli scholar Ora Rodrigue Schwarzwald, eleven Ladino editions came out of Salonica; nine from Amsterdam (in Latin letters); eight from Livorno; seven from Venice; and three each from Belgrade and Vienna. Other Ladino translations of Pirke Avot appeared within the famous Ladino work, Me’am Lo’ez, an encyclopedic commentary on the Hebrew Bible. The fact that so many translations were published is further evidence of the popularity of Pirke Avot and the desire of Sephardic Jews to be able to comprehend its teachings in their own language, Ladino.

As would be expected, the different Ladino translations of Pirke Avot reveal interesting variations in regional Ladino dialects. One of the pioneers of Sephardic Studies in the United States, David Barocas, compared the text and commentary of Pirke Avot found in the Me’am Loez editions from the Ottoman Empire with ones from Livorno, and noted the following differences in vocabulary, particularly the reliance on terms derived from Turkish in the editions published in the Ottoman Empire:

Turkish Livorno

- Presona persona person

- Para, gerush dinero money

- Apros dineros money

- Puerpo cuerpo body

- Topar allar find

- Atimo fin end

- Hatir pavor favor

- Kolay fasil easy

- Pako kovdo cubit

- Kaluf forma form, mold

- Haslak forma rough, raw

- Hazino infermo sick

Of the over fifty editions of Pirke Avot in Ladino, the University of Washington Sephardic Studies Collection holds twenty-five copies, ten of which have already been digitized. But perhaps more importantly, our collection also boasts four versions not previously accounted for, including a version contained in an edition of Me’am Lo’ez (Izmir, 1856); Rabbi Haim Shaki’s Trezoro de Djudaizmo (Cairo, 1907); the last chief rabbi of Rhodes Reuven Eliyahu Israel’s Pirke Avot: kon traduksion libera en Djudeo-Espanyol (Izmir, 1924), which is special because of the liberty with which Israel undertook the translation, preferring to capture or emphasize certain ideas rather than the literal words of the original; Nisim Behar’s Pirke Avot: livro de moral Cudia, printed in Latin letters (Istanbul, 1954); and Isaac Azose’s version in his prayer book Zehut Yosef (Seattle, 2002). There may very well be others yet to be discovered.

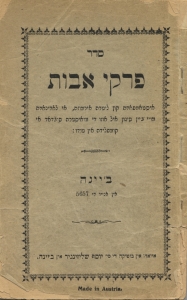

Title page of Seder Pirke Avot, published in Vienna, 1897. (Courtesy of Isaac Azose.)

The nearly half century separating the Seattle version from that which came before it is only one of the features that distinguishes the Ladino text of Pirke Avot published by Isaac Azose. It is also one of the few published in the New World. Perhaps most significantly, Azose based his version on an 1897 Ladino translation of Pirke Avot printed by the famous Schlesinger publishing house in Vienna, once home to a small but flourishing Sephardic community that also played a role in popularizing the Ladino version of the Passover song, Had Gadya.

Isaac Azose recalled that when he became the hazzan of Congregation Ezra Bessaroth in Seattle in 1966, he noticed that the custom of that synagogue and at the Sephardic Bikur Holim, also in Seattle, was to chant the Pirke Avot during the Omer based on the text from Schlesinger’s Vienna edition. Notably, even though Jews from Rhodes founded Congregation Ezra Bessaroth, they did not institute the more freely translated edition created by the chief rabbi of Rhodes, Reuven Eliyahu Israel, but rather seemed to prefer the more literal, word-for-word translation as preserved in the Vienna edition.

Given the popularity in Seattle of Schlesinger’s Seder Pirke Avot: Estampada kon letra ermoza i ladinada muy bien sigun el uzo de muestra sivdad i kumplida en todo, it is not surprising that it has been one of the most common Ladino books made available to the UW Sephardic Studies Collection. Immigrants from the former Ottoman Empire may have brought copies of this bilingual Hebrew-Ladino booklet with them to the Pacific Northwest. But it is also possible that many of the copies were purchased once the immigrants arrived in America. La Vara, a major Ladino newspaper published in New York from 1922 to 1948, regularly advertised the Ladino editions of Pirke Avot from Vienna. Subscribers to the newspaper who lived in Seattle very well could have ordered copies for themselves from La Vara’s New York office.

Even though the title of Schlesinger’s Pirke Avot indicates that the text is “according to the custom of our city” (sigun el uzo de muestra sivdad), referring to the small but important Sephardic community in Vienna, clearly it was adopted by other communities as well—including here in Seattle. Such a factor demonstrates that the traditions and practices of different Sephardic communities influenced each other.

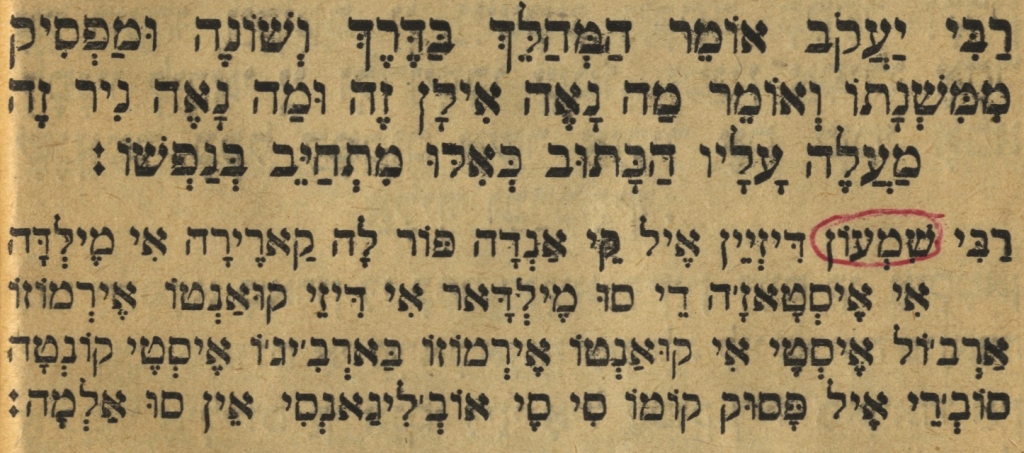

Excerpt from Schlesinger’s Ladino Pirke Avot with a notation by Hazzan Isaac Azose.

Notably, however, Isaac Azose did not duplicate the exact Ladino text of Schlesinger’s Pirke Avot. Rather Azose undertook a tremendous effort to amend, correct, and improve the language, grammar, and spelling of Schlesinger’s edition, and also transliterated it into Latin letters to make it more accessible to an American audience. You can follow the notations in Azose’s own copy of Schlesinger’s Pirke Avot which has been digitized and is now available as part of the UW Sephardic Studies Digital Collection.

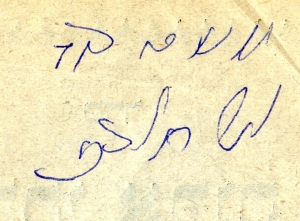

Among the unique discoveries of this particular edition, came upon opening the front cover and finding the signature of the original owner in handwritten Ladino, known as soletreo—none other than my own great-grandfather, Moshe David Alhadeff!

It is both exciting and humbling to know that a book once in my great grandfather’s possession contributed to the perpetuation of a longstanding Sephardic custom of chanting Pirke Avot in Ladino at synagogue between Passover and Shavuot. Knowing that my own family formed a link in the chain of transmission of this tradition imbues it with even greater significance, even though the meaning of the tradition has changed: while initially chanted in Ladino for congregants to understand, now Pirke Avot is chanted in Ladino in Seattle because it forms part of our rich, distinctive Sephardic tradition. It is a particular tradition that has developed from ancient Babylonia to medieval Spain, to the Ottoman Empire, Vienna, and Seattle.

Soletreo signature of Moshe David Alhadeff located on the copy of Schlesinger’s Pirke Avot used by Hazzan Isaac Azose.

(5.28) Trastorna en eya i trastorna en eya, ke lo todo en eya, i en eya veras i envyejesete, i enkanesete en eya, i de eya non te tires – ke non a ti kondisyon buena mas ke eya.

Turn it and turn it for all is in it. Gaze in it, grow old and worn out in it, and do not move from it, for there is nothing better than it.

Hazzan Azose has kindly allowed us to share his performance of the first verses of Pirke Avot from his double disk CD The Liturgy of Ezra Bessaroth at this link.

The lyrics sung by Hazzan Azose are as follows:

Isaac Azose’s Siddur Zehut Yoseph, published by Sephardic Traditions Foundation, Inc., 2002.

Translation: Moses received the Torah from Sinai and he passed it onto Joshua. And Joshua to the Elders, and the Elders to the Prophets, And the Prophets passed it onto the Men of the Great Assembly. They would say three things. Be precise in judgment. And you shall establish many students. And you shall make a fence around the Torah.

For additional resources see:

Schwarzwald, Ora (Rodrigue). The Ladino Translations of Pirke Aboth: Studies in the Translation of Mishnaic Hebrew into Judeo-Spanish. Jerusalem: Magnes Press, 1989.

Magriso, Rabbi Yitzchak (ben Moshe). Avot. 1747. MeAm Lo’ez. Ed. Rabbi Aryeh Kaplan. Trans. David N. Barocas. New York and Jerusalem: Maznaim Publishing Corporation, 1979.

Grossman, Avraham. “Legislation and Responsa Literature.“ The Sephardi Legacy. Ed. Haim Beinart. Vol. 1. Jerusalem: Magnes Press, 1992.

Leave A Comment