Haggadot collection from the Sephardic Studies Library at the University of Washington

As is said in the Passover haggadah (or aggadá as pronounced among Sepharadim): “En kada generansio i generansio es ovligado el ombre por amostrar a si mesmo komo si el saliera de Ayifto” (In each generation, everyone is obliged to behave as though he personally went out of Egypt.)

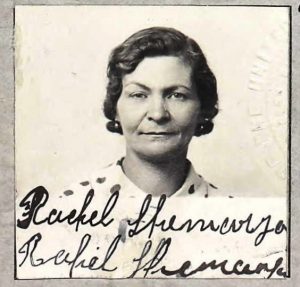

For Rachel Shemarya (née Capelouto), a native of the Island of Rhodes, Passover provided an opportunity not only to share her delicious holiday recipes but also to transmit the Passover story and Sephardic songs in her native language, Ladino, to her family right here in the Pacific Northwest. While most of the Shemarya relatives who remained in Rhodes tragically perished in Auschwitz, those who came to the United States carried the tunes to their new home as documented here in a 1971 recording.

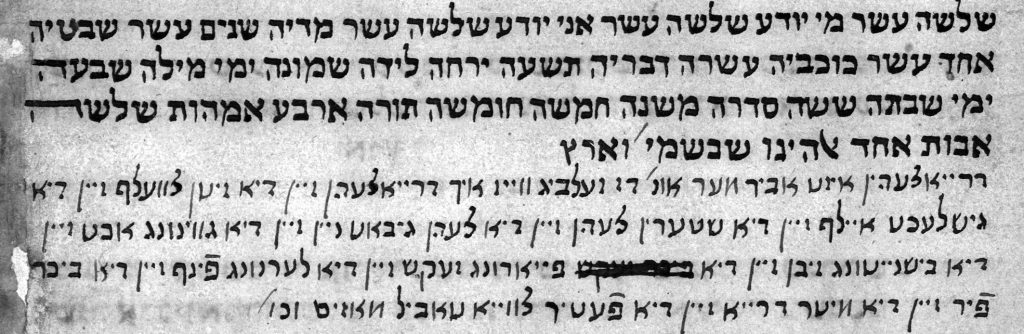

Among the songs included in the Passover seder is “Ehad Mi Yodea” (Who knows one), a cumulative song that enumerates thirteen Jewish motifs and ideas, from belief in one God to the thirteen attributes of God’s mercy with references to the biblical matriarchs and patriarchs, foundational Jewish texts, and lifecycle events along the way. Scholars surmise that this song was added to the concluding section of the Passover seder, along with songs such as “Had Gadya” (In Ladino: Un kavretiko), as a way to keep the attention of children while imparting Jewish knowledge to them. The manuscript of the Prague Haggadah (1526), the earliest complete illustrated, or illuminated, haggadah, seems to be one of the first known appearances of both of these songs. But according to Encyclopedia Judaica, a definitive reference book of Jewish knowledge, Ehad Mi Yodea exists only in the “Ashkenazi rite.” So if this were true, why is Rachel Shemarya and her Sephardic family chanting the song—and in Ladino no less?

The 13th stanza of Ehad Mi Yodea in Hebrew and Yiddish from the Prague Haggadah manuscript, 1526. Courtesy of the National Library of Israel

The omission from the Encyclopedia Judaica of Ehad Mi Yodea in the Sephardic tradition is certainly one of innumerable examples of the Sephardic experience being excluded from mainstream Jewish narratives. But a comprehensive review of Sephardic haggadot reveals that most do not contain the text of Ehad Mi Yodea either in Ladino translation or in the original Hebrew, not even the haggadah included in the famous Ladino biblical commentary, Me’am Lo’ez. Of the roughly thirty editions of Sephardic haggadot accounted for—ten from places like Livorno, Vienna, Salonica, Istanbul, and New York all housed in our Sephardic Studies Collection and more than twenty cataloged by scholars Ora Rodrigue-Schwarzwald and Aaron Maman—less than a third include Ehad Mi Yodea in Hebrew. Only two include it in the Ladino translation, known as Ken Supiense.

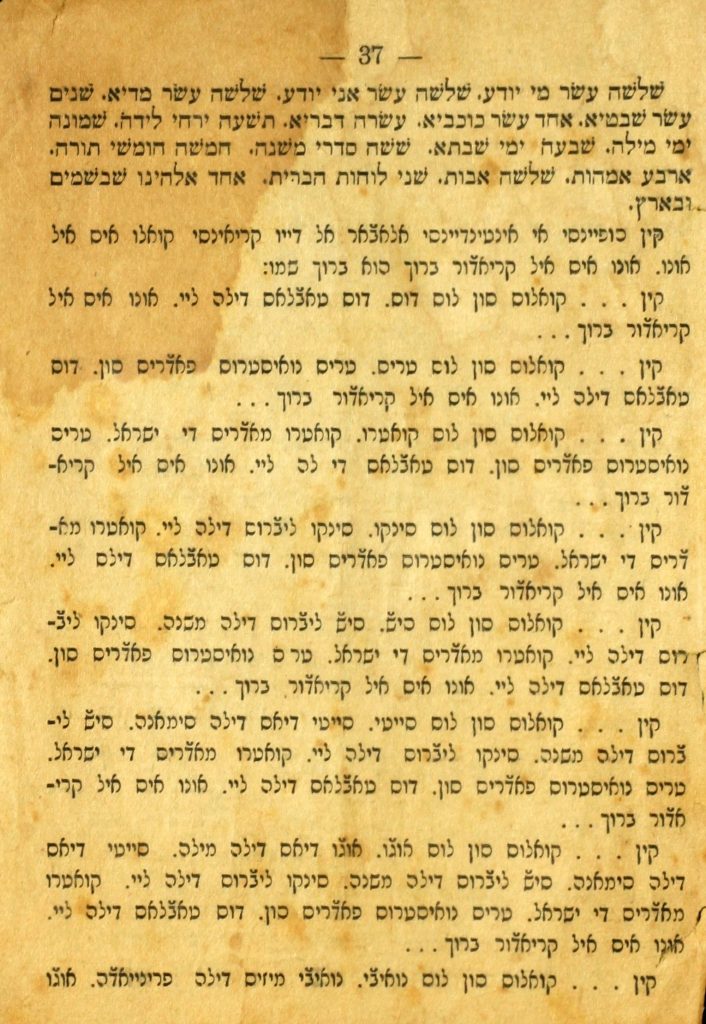

Schwarzwald and Maman identified one haggadah from Turkey that included Ken Supiense published in Latin characters—a sign that it was printed after the 1920s, when the new Republic of Turkey instituted a modernizing alphabet reform. The other one, from our collection at the University of Washington, was printed in Hebrew characters (specifically rashi script), a sign that it is older. That version of Ken Supiense is a faithful translation of the original Hebrew and is found in an unknown Ladino haggadah (UW 779) from the collection of the late Mr. Leo Azose, a Seattle resident and leader of the local Sephardic community. This haggadah is “unknown” insofar as the cover and title page are missing as are any clues to its place or date of publication. Based on the font and paper quality, we can assume that it was published in the late 19th or early 20th centuries, but more research would be required to confirm this hypothesis.

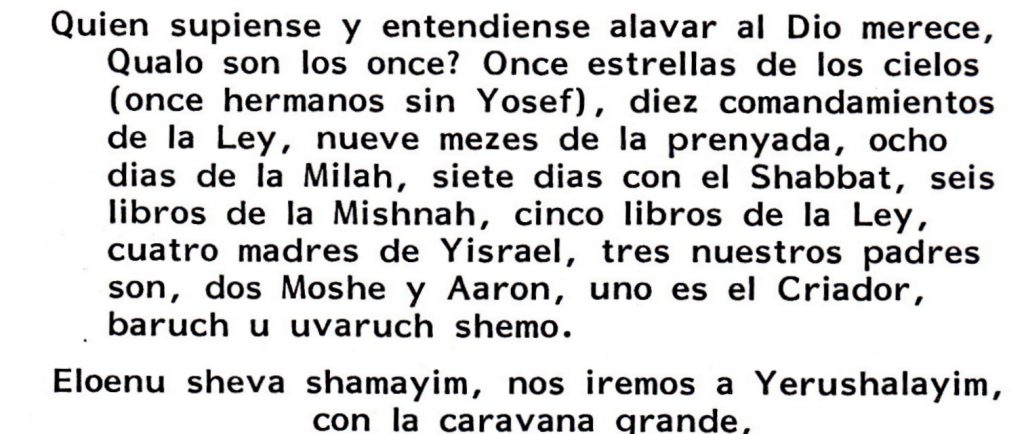

Ken Supiense from an unknown Ladino Haggadah (UW 779). From the collection of Leo Azose, courtesy of his grandson Larry Azose.

Regardless of the precise path through which Ken Supiense entered the Sephardic Passover canon, and as equally remarkable as the limited representation of Ken Supiense in printed Sephardic haggadot, is the extent to which the wording of the oral recording from Rachel Shemarya—which she sang from memory—differs from the printed text. Not only that, but an exploration of other audio recordings of Ken Supiense—not only from Rhodes but also from other locales in the former Ottoman Empire, including Salonica and present-day Turkey, and recorded in Seattle and in Israel—reveals a wide variety of differences in the wording of the song and the melody.

All versions of Ehad Mi Yodea, whether in Hebrew or in Yiddish or Ladino translation, agree that, among the thirteen Jewish references enumerated in the song, one always refer to one God and five always refers to the five books of the Torah. But there are some major variations among the Ladino versions. For example, in oral recordings based on the Salonica and Rhodes traditions, the song includes a kind of redemptive, rhyming preamble half in Hebrew and half in Ladino: “Eleonu she-ba-shamayim, nos iremos a Yerushalayim, kon la karavana grande” (Our God in Heaven, we will go to Jerusalem with a great caravan

Other variations abound. According to the Hebrew text, the number two represents the two tablets of the covenant that Moses received at Sinai, yet we find that most Sephardic communities replaced the reference to the tablets with the names of two of the great leaders in the Passover story, Moshe and Aaron. In Rhodes and Salonica, the names of the Patriarchs Abraham, Yitzhak and Yaakov are added, as are the names of Matriarchs Sara, Rivka, Lea, Rahel (the latter of which conveniently rhymes with “madres de Yisrael”).

Perhaps one of the most intriguing differences can be discerned in the varied references in the final, thirteenth stanza of Ken Supiense. The Rhodesli and Turkish versions do not refer to the thirteen attributes of God’s mercy as the original Hebrew text does, but rather to renowned medieval Spanish sage Rabbi Moses Maimonides’ Thirteen Principles of Faith that he outlined in his famed commentary on the Mishna, and which are popularly known today from Sabbath songs like “Yigdal” and “Adon Olam.”

The specific importance of these thirteen principles from the Sephardic perspective is reflected in the Ladino saying: está en sus treje (He is standing on his thirteen), meaning that one is holding strong to his faith. According to Sam Bension Maimon in The Beauty of Sephardic Life, popular legend has it that this expression goes back to the days of the Spanish Inquisition when an inquisitor would ask someone suspected of practicing Judaism in secret: “Está en su treje?” meaning: would this person abandon or stay steadfast to his belief in the Thirteen Principles of Faith?

The Azose family singing “Ken Supiense” according to the Turkish tradition in the film Song of the Sephardi

Regardless of the fanciful link to the Inquisition, Ken Supiense refers explicitly to one of Maimonides key concepts and signifies the transformation of a song of Ashkenazi origin into one with fundamentally Sephardic allusions. The reference also demonstrates that high ideas expressed in writing by Sephardic sages like Maimonides penetrated the collective consciousness of the Sephardic masses through oral tradition—evidence of the importance of taking into account written and oral traditions together.

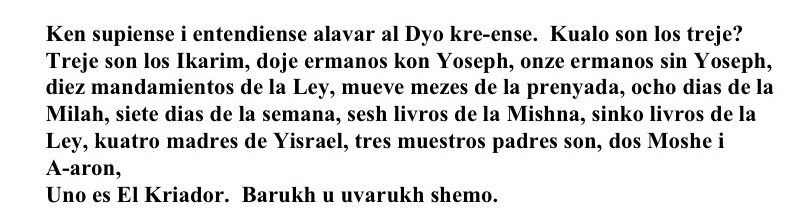

The 13th stanza of Ken Supiense according to the Turkish custom, from Isaac Azose’s Agada De Pesah, Seattle, WA 2011.

The case of Salonica includes a completely different reference for the number thirteen in Ken Supiense. (See the Salonican version of Ehad Mi Yodea recorded in 1982 by Dr. Susana Welch-Shahak, available here [beginning at minute 39:00], from the National Library of Israel). Rather than evoke the thirteen attributes of God’s mercy or Maimonides’ Thirteen Principles of Faith, the Salonican version departs considerably from the original Hebrew text and refers to “ermanos kon Dina”: Joseph and his eleven brothers who initiate the twelve tribes of Israel, plus their sister Dina.

At this point, we can only speculate as to why Dina is included here. Could her inclusion be interpreted as a kind of feminist gesture that says that women ought to count? Or perhaps, as described in the Me’am Lo’ez, the most important Ladino biblical commentary, the significance of the story of Dina (who, according to Genesis 34, is the victim of rape) is to reinforce patriarchy and remind men—fathers and brothers—that it is their responsibility to protect their women. Or perhaps, as also explained in the Me’am Lo’ez, the significance of Dina lies in her ability—and by extension, the power of each woman—to improve the morality and behavior of her husband. The Me’am Lo’ez deduces this conclusion from Dina’s later marriage to Job, who not only becomes an Israelite but also a holy figure—a transformation the Me’am Loez attributes to Dina’s positive influence.

Whichever interpretation one goes with–and there are likely many others–the variations among the different versions of Ken Supiense not only ought to entertain the children at the conclusion of the Passover seder, but also provoke a thoughtful discussion among the adults regarding the meanings and messages embedded in the numerous Ladino versions of the song.

The variations in the lyrics are also matched by variations in the song’s melody—additional signs not only of the internal diversity and richness of Sephardic traditions, which varied from one community to another, but also of the extent to which these songs likely survived through oral transmission, from one generation to the next. Mrs. Shemarya’s version, for example, is slower and more of a dirge than the upbeat tempo of the Turkish and Salonican versions.

Photograph from Rachel (Rahil) Shemarya’s Petition for Naturalization, November 1941, courtesy of Ancestry.com

Her version reflects not only the lyrical tradition from Rhodes, but if you listen closely you will hear the distinguishing features of the Rhodes’ dialect of Ladino, which is characterized by what linguists refer to as “vowel raising”: “e” becomes “i” and “o” becomes “u”. You can hear these nuances in Mrs. Shemarya’s recording as she refers to “kuatru” instead of “kuatro,” “simana” instead of “semana,” “Mushe” instead of “Moshe,” “onzi” instead of “onze,” “sieti” instead of “siete,” “muevi” instead of “mueve,” “muestrus” instead of “muestros,” and “intendiense” as well as “entendiensi” instead of “entendiense.”

The differences in wording, pronunciation, and melody become clear when considering the various versions of the song together. Compare Mrs. Shemarya’s rendering to that presented in the 1978 film documentary film Song of the Sephardi, which features a performance of the song by Seattle’s Hazzan Isaac Azose and his family. Years later Azose also recorded the song on his double disc CD “The Liturgy of Ezra Bessaorth.”

Some of the leaders of Seattle’s Sephardic Bikur Holim, namely Sam Bension Maimon, Reverend Samuel Benaroya, Rabbi Solomon Maimon, and Leo Azose recorded a similar version on the 1980 cassette recording “The Sephardic Ladino Tradition: Judeo-Spanish religious songs and liturgical chants: according to the Turkish Balkan tradition.” What’s remarkable here is that even though Leo Azose had access to the direct, word-for-word Ladino translation of Ehad mi-Yodea, the version in the recording follows the Turkish oral tradition.

In 1995, Hazzan Isaac Azose and Elazar Behar each produced their own editions of the haggadah in English, Hebrew and Ladino, which included the Rhodes and Turkish traditions of Ken Supiense, printed in Latin letters for the benefit of the Seattle Sephardic community, thus ensuring that future generations will “know and understand” the now traditional seder standard, “Ken Supiense.”

The 11th stanza of Ken Supiense according to Rhodes tradition, from Elazar Behar’s Seder ha-Haggadah shel Pesah, Seattle, WA 1995.

From our excavation of the varying versions, styles, and sounds of Ehad Mi Yodea in Ladino, we learn that in order to understand the richness of Sephardic traditions and customs, we must not only study published texts, but also make recourse to the oral tradition. As in traditional Judaism, in general, according to which the Written Law cannot be fully comprehended without reference to the Oral Law, so too must Sephardic traditions be recognized as an ongoing dialogue between the written and oral domains. It is a dialogue that has transmitted key intellectual concepts of Judaism—like Maimonides’ Thirteen Principles—to the masses, and one in which not only men have played leading roles, but also, as evidenced by Mrs. Shemarya’s recording, women, too.

This year, consider singing Ken Supiense in Ladino according to one of various Sephardic traditions at your Passover seder!

Pesah alegre!

For your enjoyment, we have transcribed the 13th stanza according to the Salonican tradition based on Dr. Susana Welch-Shahak’s recording:

Eleonu she-ba-shamayim, nos iremos a Yerushalayim, kon la karavana grande. Kualo son los tredje? Tredje ermanos kon Dina, dodje ermanos kon Yosef, onze ermanos sin Yosef, diez mandamientos de la Ley, mueve mezes de la prenyada, ocho dias de huppa, siete dias de la semana kon Shabbat, sesh dias de la semana sin Shabbat, sinko livros de la Ley, kuatro madres de Yisrael, tres muestros padres son, dos Moshe i Aaron, primero es El Kriador. Baruh u u-baruh Shemo.

For additional resources see:

“Had Gadya: A Sephardic Passover Tradition” by Devin Naar

“A Ladino Haggadah with Woodcuts and Wine Spills” by Hannah Pressman

Ora Rodrigue Schwarzald and Aaron Maman, Milon ha-hagadot shel Pesah be-Ladino (“A dictionary of the Ladino Passover Haggadot) (Jerusalem: Y.L. Magnes, Hebrew University, 2008) (In Hebrew)

Special thanks to Hazzan Isaac Azose for producing this song in film, text, and musical recordings, as well as allowing us to include samples of his work in our research. Thanks to Ralph Maimon for notifying us that Hazzan Isaac Azose’s “Agada de Pesah” was the result of a collaborative effort with Isaac Maimon, Sarah Benezara and support from Morris Piha.

We are grateful to Rachel Shemarya’s son Albert Shemarya not only for his contribution of Ladino texts and recordings but also for his active support to the Sephardic Studies Program where he has presented and sung at all four International Ladino Day Events at the University of Washington.

Additional thanks to PhD Student Molly FitzMorris at the University of Washington’s Linguistic Department for her insights into Rachel Shemarya’s recording of Ken Supiense. Ms. FitzMorris is undertaking an in-depth study of the Rhodes dialect of Ladino and the phenomenon of vowel raising.

Ty, what a beautiful article and so well researched and set forth by you for our reading pleasure and for that of future generations..

Just one correction, the new Sephardic Haggadah that you mention was not only produced by my cousin, Hazzan Azose. It was the brainchild of my father Isaac Maimon (a”h) (when he was requested by and then graciously funded by Morris Piha (a”h). In fact, it was produced as a joint effort among my father, Sarah Benezra (both a”h) and Hazzan Azose. I am sure that the “error” in attribution was a from the erroneous preamble in the Haggadah that implies otherwise. I simply want to set the record straight and give my beloved father the credit he deserves after a life of dedication and service to our entire Seattle Sephardic community.