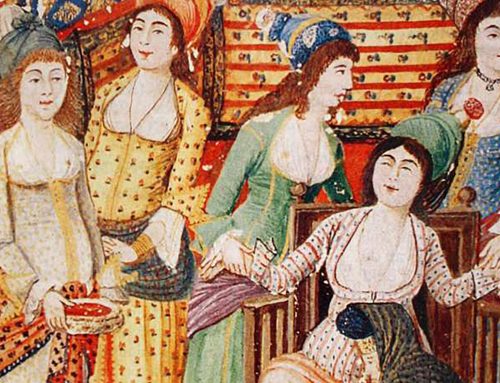

Egyptian Jews. Photo courtesy of Beit Hatfutsot.

By Pablo Jairo Tutillo Maldonado

The experience of the Jewish people is a story with many facets. It is a story of refugees, a story of exile, a story of enlightenment, a story of genocide. It is also a story of political movements, a story of religion, a story of history, and a story of philosophy.

Yet this is not a unique history.

According to a March 2017 Report from the United Nations Refugee Agency, there are more than five million Syrian refugees who have fled their country as a result of government crackdowns and internal civil conflict. In addition, there are also Syrian, Iranian, Iraqi refugees being persecuted for being gay, lesbian, bisexual or transgender. The number of refugees globally is now at a record high.

However, this is not a novelty for the region. After Israel’s independence in 1948, apart from hundreds of thousands of Palestinians who became refugees in that time, approximately 850,000 Jewish refugees fled from their native countries — ranging from Egypt, Algeria, Syria, Tunisia, Morocco and Yemen — amidst accusations of being accomplices and spies at the time of the State of Israel’s independence.

While perhaps refugees from the Middle East gain the most media attention, it is not the only region with a current refugee crisis. From Bangladesh to Darfur, millions of people are moving across territories in search of a safe place. In fact, Latin America, although less talked about, has faced an alarming refugee crisis and displacement of people in Colombia, Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador, where people have fled violent gangs, guerrillas and government crackdowns.

Plane filled with Iraqi Jews, 1951. Photo courtesy of World Jewish Congress.

My own research is on the experience of Jewish refugees from the Arab world in the aftermath of 1948, which will in turn help me understand the causes and conditions — on a global level — that lead to expulsion and exodus.

Analyzing the history of refugees through a comparative regional approach is essential to addressing the contemporary crises around the globe. Moreover, I think it is important to learn how the stories of these refugees have been recorded in history books, how they are preserved in the memory of people and how governments tackle with acknowledging the expulsion of their citizens. Countries like Egypt, Yemen and Algeria have yet to recognize the hardship experienced by the Jewish communities in their countries.

Indeed, failing to recognize particular histories is not unique to these countries. For example, China has had a difficult time in recognizing the crackdown of Tiananmen Square, and Turkey has yet to recognize the Armenian genocide. Japan also maintains a sensitive relationship with Koreans who remember abuses during the imperial era. Israel also has yet to recognize the plight of the Palestinian exodus. Colombia has yet to account for thousands of displaced and disappeared civilians.

Overall, the question for the countries of the Middle East is whether they will recognize the plight of the Jewish communities that thrived and contributed so much to their societies in the Arab world.

Will this history be remembered? And what is at stake? By studying Jewish refugees in the Middle East, I hope to bring to light the conditions that led Jews to flee or be expelled from their countries, so that we may have a better understanding of what happened and what we can do better today to improve the well-being of citizens in their countries, to understand how authoritarian regimes have been affecting the relations with minority religious communities, sexual minorities, women and all human beings. I study this history so we can give all people the dignity of human rights.

Pablo Jairo Tutillo Maldonado is an M.A. student in Middle East Studies at the Henry M. Jackson School of International Studies. Pablo holds a BA from Connecticut College, and has studied at Alexandria University in Egypt and at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem in Israel. Pablo’s work looks at the intersection of history and politics of countries in the Middle East, particularly the political and historical narratives of Jewish refugees from the Arab world. Pablo speaks Arabic, Hebrew, Turkish, and Spanish, and currently holds the Mickey Sreebny Memorial Fellowship in Jewish Studies.

Leave A Comment