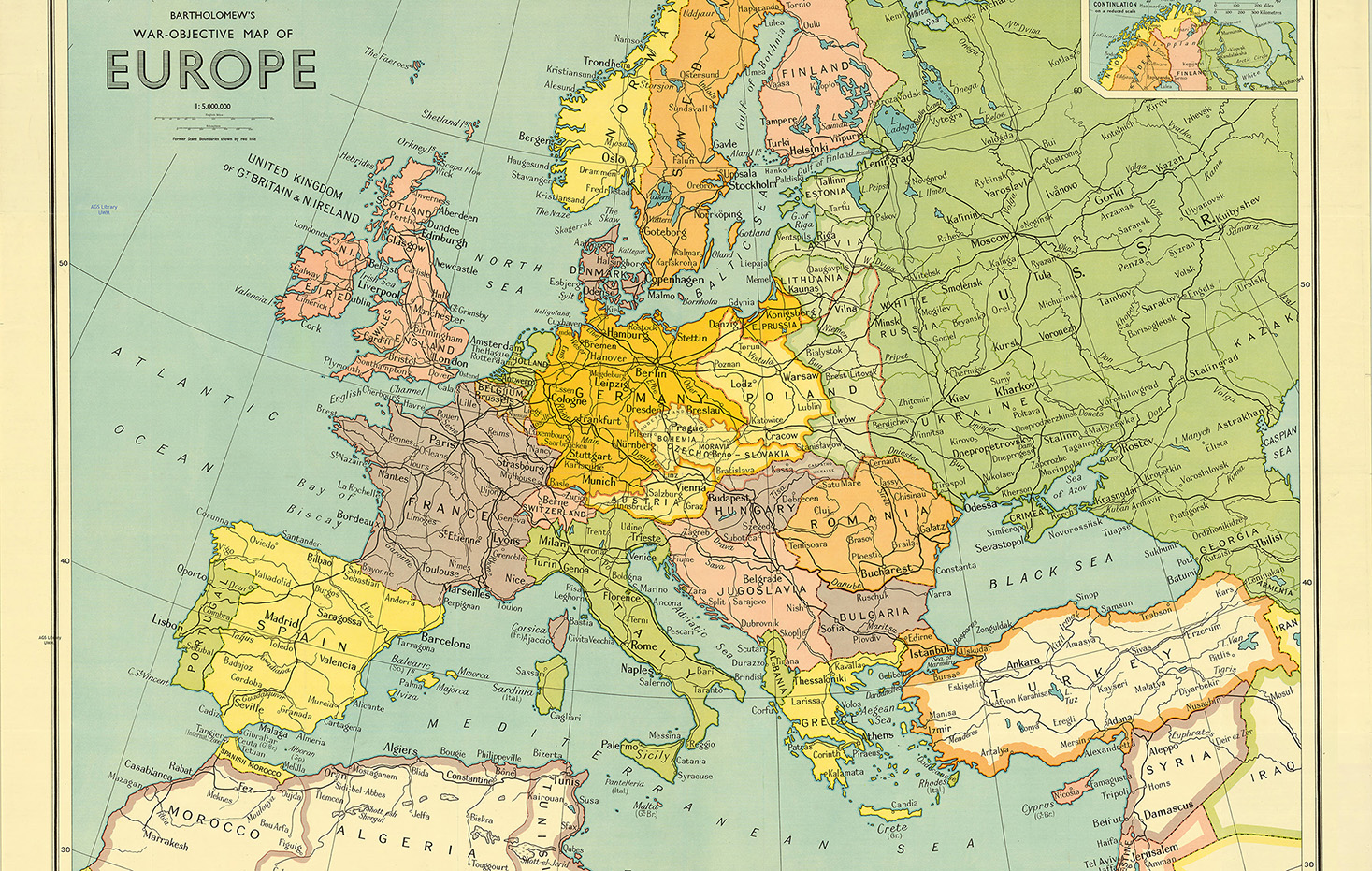

Bartholomew’s map of Europe, 1940. Via the University of Wisconsin Milwaukee Libraries.

By Joana Bürger

In the summer of 2022, I spent some weeks in Jerusalem conducting research at the Central Archives of the History of the Jewish People, an important archive on the campus of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem that houses a cache of documents from global Jewish communities. While the scorching sun was burning outside, I crouched over files from the Jewish communities of Turkey, looking for traces of central European Jewish refugees who fled to the region around the Aegean Sea (in present-day Greece and Turkey) due to the Nazis’ rise to power in Germany in 1933.

Suddenly, my gaze fell on a curious document. I was holding a typed letter in my hands sent by Alfons Eskenasy from Munich, Germany, to the chief rabbi of Istanbul, Turkey, in 1942. Writing in a mix of broken Ladino (Judeo-Spanish) and fluent French, Eskenasy was asking the chief rabbi for help in regaining his former status as a Turkish citizen.

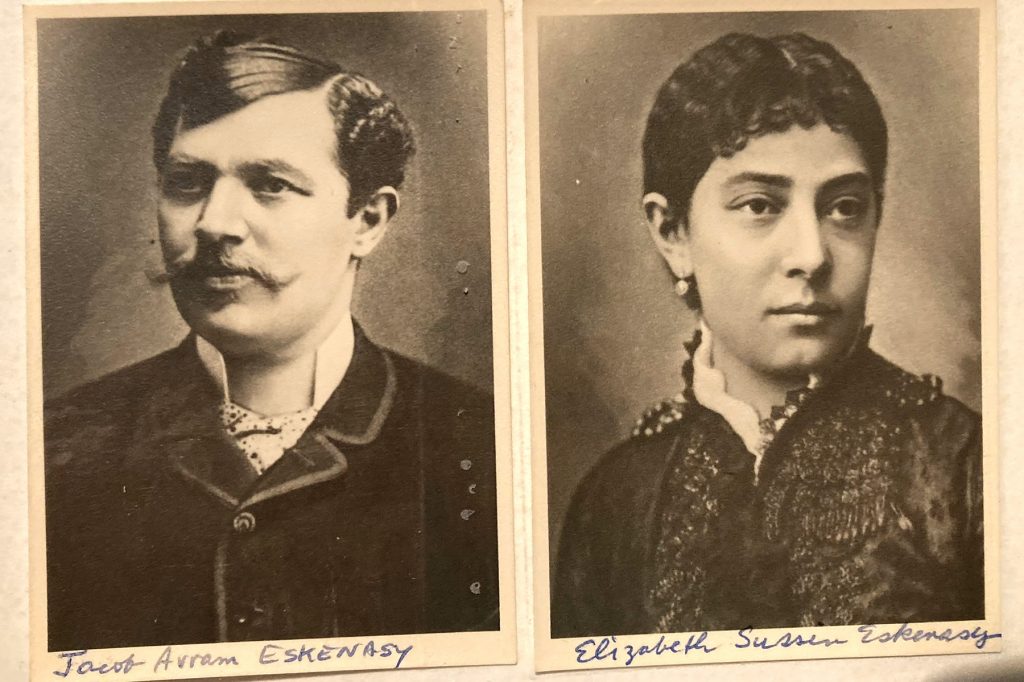

In the letter, Eskenasy explained that he had been born in Vienna (in present-day Austria) in 1881 to a family of Sephardi Jewish immigrants from the Ottoman Empire, and that he had moved to Munich in 1909. Despite this connection to the Ottoman world, the Turkish consulate in Berlin had renounced his status as Turkish citizen in 1936, after he tried to apply for a Turkish passport to leave Nazi Germany with his wife and his two daughters.

Alfons’ parents, Jacob Avram Eskenasy and Elizabeth Sussin Eskenasy.

I was intrigued by the fact that this letter had been sent from a Sephardi Jew living in Nazi Germany to Istanbul at the height of the Holocaust. Scholarship on the lives of Ottoman Sephardi immigrants in central Europe and their fate during the Holocaust is very limited. Nonetheless, the story of Eskenasy losing his Turkish citizenship was not unique.

Ottoman minorities, the loss of Turkish citizenship, and the vulnerability of stateless Jews

The Ottoman Empire, which controlled the region of the eastern Mediterranean for many centuries until it collapsed as a result of World War I, was characterized by social segregation along religious lines (the millet system). While it was a Muslim empire, Christians and Jews enjoyed certain protections as “people of the book” (followers of other Abrahamic religions).

In the 1920s, the new Turkish state — which succeeded the Ottoman Empire and was established in the region of Anatolia — started to replace the Ottoman identity papers of former Ottoman citizens living abroad with modern nationality certificates. With the goal of creating a religiously and ethnically homogeneous group of citizens, Turkish officials used this process to slowly strip non-Muslim Ottomans of their status as Turkish citizens — a common process in nationalist movements in this era. While initially affecting all religious minorities, by the 1930s this policy of revoking citizenship increasingly targeted Turkish Jews.

While reading this letter, I also knew from the literature that most stateless Jews in Nazi Germany — those without confirmed citizenship in any other country — were among the first people to be deported to concentration camps. Hence, after finding this letter, I assumed that the Eskenasy family did not survive the Holocaust. But the database of Yad Vashem, the world Holocaust Remembrance Center in Jerusalem, revealed that Alfons Eskenasy and his two grown-up daughters had been deported to Theresienstadt Ghetto — located in modern-day Czechia, close to the eastern border of Germany — in January of 1945. And against all odds, they survived!

Searching for the Eskenasy family in the United States

My detective spirit roused, I continued looking for traces of the Eskenasy family after the war and eventually discovered that they had moved to New York City in the United States in 1947. And not only that, Louise Eskenasy – Alfons’ older daughter – fell in love with an American soldier who was stationed in Munich after the war. This soldier, Lloyd James McGaughey, was originally from the town of Leavenworth, Washington. After arriving in the United States, Louise moved to Leavenworth to marry Lloyd, and she brought her daughter, Inez — who was born in Nazi Germany in 1938 — with her.

Through some Internet digging, I found a phone number. The eighty-five year-old Inez McGregor, granddaughter of Alfons Eskenasy, whose letter I had found in Jerusalem, lived in a small town only an hour drive away from Seattle, where I was sitting at my laptop doing research. I couldn’t believe the coincidence! So one day, full of excitement and not at all sure that I had found the right person, I picked up the phone and called Inez. And indeed, I spoke to Alfons’ granddaughter.

Inez shows Turkish flags contained in the suitcase of Eskenasy family history

Not only did she invite me to lunch, but she also literally opened up her past in front of me. After we ate, drank and talked, her husband brought out an old trunk. The family had used this suitcase when they were immigrating to the United States almost 76 years ago. Inside, Inez kept a family photo album with pictures going back to her great-grandparents, who had moved from the Ottoman Empire to Vienna; the yellow star that her mother had been forced to wear; and old family documents. From the documents and Inez’s account, I pieced together the story of the family’s survival.

A cosmopolitan, multicultural family in 20th-century Munich

Alfons Eskenasy had moved to Munich in 1909 to work as an opera singer. There, he married Louise Lea Hafner, a Catholic German woman, and they had two daughters, Louise (born in 1911) and Carmen (born in 1923). Besides singing at the opera, Alfons was a talented photographer with his own studio, and he took pictures of famous German singers and actors during the period between World War I and World War II.

Louise (left), her young daughter Inez (middle), mother/grandmother Louise Lea (middle), and Carmen (right), 1938.

The family’s photo album exhibits his great sense of humor and his talent for capturing intimate family moments. Through these pictures, I gained a glimpse into the pre-Nazi life of an extraordinary, cosmopolitan, open-minded family. While they celebrated Christmas and decided to baptize their children, they also organized a bat mitzvah for their oldest daughter. While German language and music filled their home, they also had a portrait of the Turkish revolutionary hero Atatürk and Turkish flags hanging in their living room.

Following Hitler’s rise to power, Alfons was deported to the concentration camp in Dachau, close to Munich, because of his Jewish background. According to the Nazis’ racial laws, which came into effect in 1935, a person was considered Jewish and lost their political rights if they had at least three Jewish grandparents. Shortly after his incarceration, however, Alfons was released, probably due to his marriage to a non-Jewish German woman. (Initially, the Nazis hesitated to deport members of mixed families because they were afraid to cause an uproar in German society.)

Attempted escape, forced labor, and deportation to a concentration camp

After his release, Alfons tried to get his family out of Nazi Germany, but the Turkish state refused him a Turkish passport. So the family bought tickets to travel by boat to Tangier in Morocco instead, but before they could embark to safety, World War II broke out.

Despite being baptized, the Nazis considered Louise and Carmen as half Jewish and forced them to work at a battery factory in Munich. Their mother, who refused to divorce her Jewish husband, was also forced into hard labor. During their time at the factory, Louise and Carmen engaged in clandestine resistance activities, providing imprisoned forced laborers from Ukraine with extra food and even helping an English prisoner of war to escape.

At the same time, Louise was worried for the safety of her four-year-old daughter, Inez. With the help of a French engineer who periodically traveled to Munich to work at the factory, she managed to find a hiding place for her child in a Bavarian village a few hours away from Munich. They brought little Inez to Bad Schliersee, close to the Austrian border, where she stayed with a Mrs. Schneider from 1942 to 1945. In January of 1945, Alfons and his daughters were deported to the Theresienstadt Ghetto. Miraculously, they managed to survive, and upon liberation they returned to Munich, where the family was reunited.

An incredible story, a museum in a trunk: The Eskenasy family’s “mosaic” of experiences

My archival research in Jerusalem, which initially focused on the fate of Jewish refugees in Turkey, revealed a case of the Turkish state refusing former Ottoman Jews Turkish citizenship and thus blocking their way to safety in Turkey. The story of the Eskenasys’ survival exemplifies not only the understudied trajectory of Ottoman Sephardi immigrants in central Europe, but also gives us valuable insights into the fate of stateless Sephardi Jews during the Nazi period.

Furthermore, this research offers glimpses into the pre-war life of a mixed Jewish and non-Jewish couple in Imperial (1871-1918) and Weimar Germany (1918-1933) and shows how they negotiated the different aspects of their identity. For the Eskenasys, being culturally German, affiliated with Judaism and proud of their Turkish origins did not create any contradictions.

The Eskenasy family trajectory links Istanbul to Vienna, Munich, Theresienstadt Ghetto, New York City, and Washington state. The family crossed state borders, switched religious categories, and changed citizenship several times. Born as a Sephardic Jewish Ottoman subject in Vienna, Alfons Eskenasy lived as a Catholic Turkish citizen in Germany – though the Nazi racial laws still counted him as a Jew and the Turkish state pushed him into statelessness – before immigrating to the United States. Eventually, he died as a resident of New York City and was buried in a Jewish cemetery.

Today, an old trunk full of family photographs and documents, which traveled from post-war Germany to Washington state, opens a window into the past of this Sephardi-Catholic-German-Turkish family and their incredible survival during the Holocaust.

The story of the Eskenasy family, which defied any clear national, religious or ethnic categorization, constitutes a mosaic of both the Jewish and non-Jewish experience of political and racial persecution during the Nazi regime.

Joana Bürger is a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of History who studies Jewish refugees in the eastern Mediterranean in the interwar period. After receiving a B.Sc. in Psychology at Potsdam University in Germany, she completed an International Research M.A. in Middle Eastern History at Tel Aviv University in Israel. Her M.A. thesis focused on Greco-Jewish identity formation in early 20th century Corfu and Athens. Joana became familiar with digital approaches to Holocaust remembrance while working as a translator for the oral history project “Memories of the German Occupation in Greece,” conducted by the Freie Universität Berlin and the National Kapodistrias University of Athens. Her research interests are modern Mediterranean Jewish history, migrations in the Eastern Mediterranean in the interwar period and comparative Holocaust memory. For her Ph.D. dissertation, Bürger is researching the Aegean (Greece and Turkey) as a multidirectional transit space for Jewish refugees in the 1930s and 1940s. She is the 2023-24 Mickey and Leo Sreebny Memorial Fellow in Jewish Studies.

Joana Bürger is a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of History who studies Jewish refugees in the eastern Mediterranean in the interwar period. After receiving a B.Sc. in Psychology at Potsdam University in Germany, she completed an International Research M.A. in Middle Eastern History at Tel Aviv University in Israel. Her M.A. thesis focused on Greco-Jewish identity formation in early 20th century Corfu and Athens. Joana became familiar with digital approaches to Holocaust remembrance while working as a translator for the oral history project “Memories of the German Occupation in Greece,” conducted by the Freie Universität Berlin and the National Kapodistrias University of Athens. Her research interests are modern Mediterranean Jewish history, migrations in the Eastern Mediterranean in the interwar period and comparative Holocaust memory. For her Ph.D. dissertation, Bürger is researching the Aegean (Greece and Turkey) as a multidirectional transit space for Jewish refugees in the 1930s and 1940s. She is the 2023-24 Mickey and Leo Sreebny Memorial Fellow in Jewish Studies.