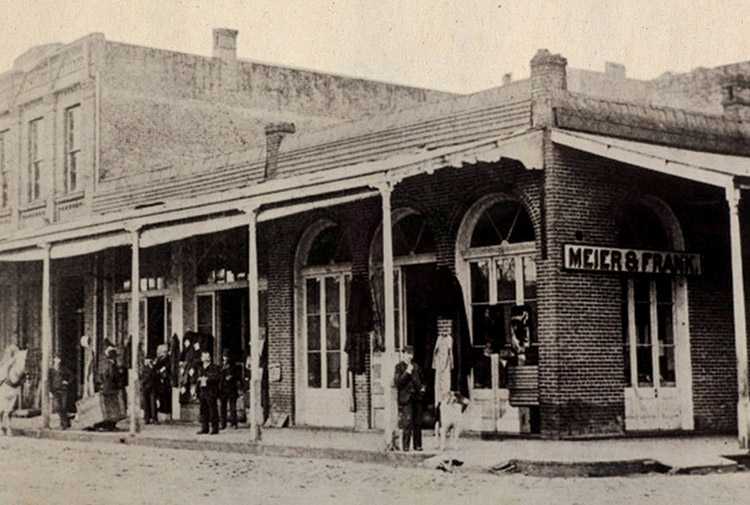

Jewish-owned Meier & Frank general store. Photo from “Jews on the Frontier: Religion and Mobility in Nineteenth-Century America” by Shari Rabin.

By Shari Rabin

For most people, American Jewish history is the story of immigration to a few major urban centers like New York City in the years between 1880 and 1924. This is not the whole story, however.

The first mass migration of Jews to the United States occurred between roughly 1820 and 1880. These Jews — a majority of whom were from German-speaking lands and most of whom were young men — fled the economic challenges and political struggles of their home countries, arriving in a new nation in the throes of westward expansion.

Seen by the government not as Jews but as, in the language of the 1790 U.S. Naturalization Act, “free white people” who were capable of becoming citizens, many American Jews quickly headed westward, many of them working as peddlers who sold goods door-to-door, relocating repeatedly in search of a secure and profitable place to settle.

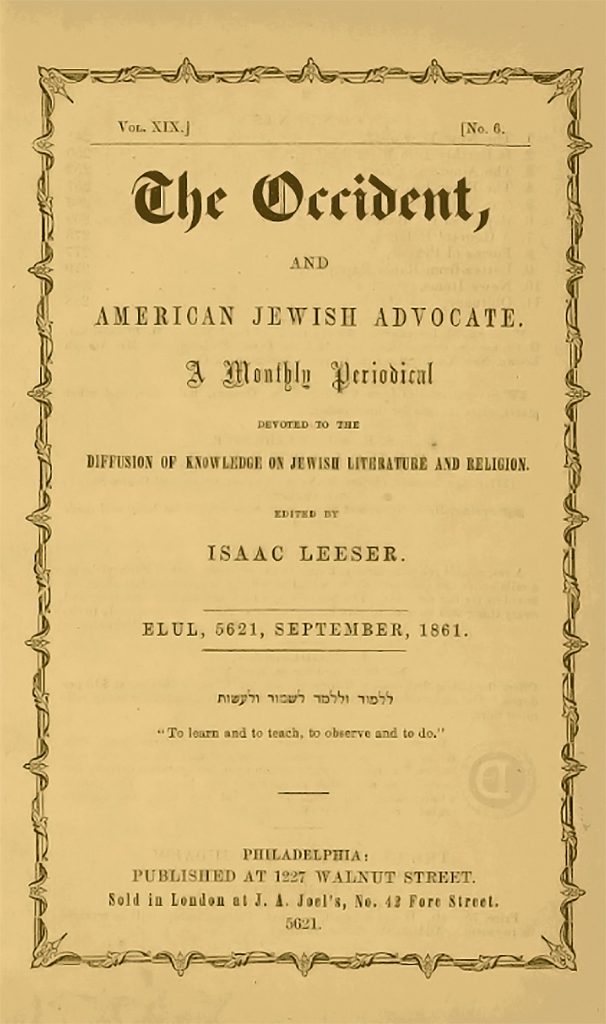

September 1861 edition of the Occident & American Jewish Advocate. Via the National Library of Israel.

Jews could soon be found in towns and cities throughout the American continent. According to historian Rudolf Glanz, before the Civil War Jews could be found in 1,000 different towns and cities in the United States, including many places in the American West. For instance, in 1855, Jewish settler Moses Abram wrote to Philadelphia’s Occident and American Jewish Advocate from Portland, Oregon, to report, “in this place are about 25 Jews 2 families we are trying to get a Jewish burying ground.”

While freedom of movement was good for Jews’ economic life, it raised real challenges for traditional Judaism. Surrounded by non-Jews, it could be hard for Jews in far-flung places to find the resources needed for traditional Jewish life: nine other Jewish men for a Jewish prayer quorum (or minyan), a skilled kosher meat slaughterer, a prayer book. These things were both hard to find and hard to verify because there were very few religious authorities. The United States only got its first rabbi in 1840, and even after Rabbi Abraham Rice’s arrival, most communities were served by non-ordained hazanim, or religious functionaries.

Furthermore, cities and states throughout the nineteenth century had laws against working on Sunday, which made abstaining from work on Saturday, and observing the Sabbath, almost impossible for many. On the road, and in the absence of established communities, then, Jews often departed from the strictest standards of Jewish law, creating Jewish communities, families, practices and beliefs on their own terms.

Even in communities that had religious leaders — whether they were rabbis or not — there were often disagreements between these leaders and their congregations, and among congregants, who were used to European Jewish institutions that were funded by taxes rather than voluntary contributions.

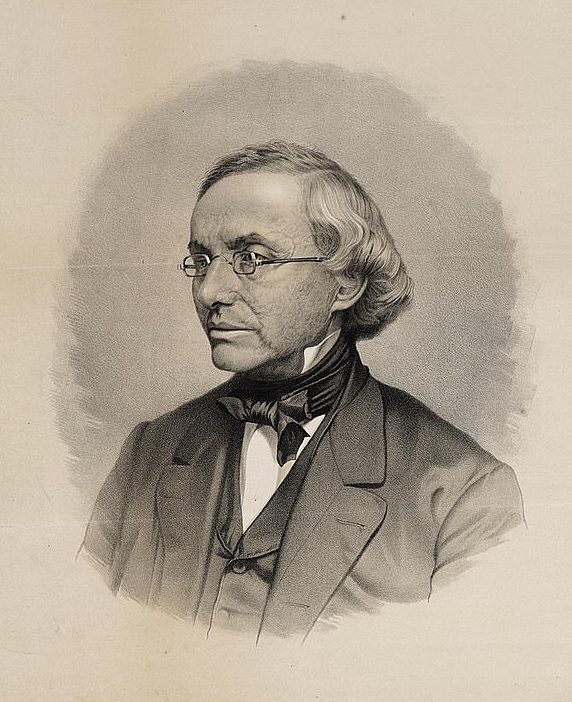

Writer, editor and publisher Isaac Leeser (1806-1868). Via Wikimedia Commons.

For American congregations, rabbis functioned more as paid employees than revered authorities. For instance, in Portland in 1873, hazan Moses May (it is not clear whether or not he was an ordained rabbi) complained that no one seemed sure which minhag, or custom of religious worship, he should follow: “I stand in the midst of chaos of forms…I would beg the worthy cong[regation] to give me a plan of the alterations you have made and how you want your service conducted in the future even if you don’t desire any other minhag than minhag Portland.” In May’s case, conflicts over these issues eventually resulted in a gunfight between the hazan and a congregational leader!

National Jewish leaders like Isaac Leeser and Isaac Mayer Wise looked at the eclecticism and instability of Jewish life in places like Portland and sought to impose order and certainty on them. To that end, they argued for the introduction of a singular minhag, or style of liturgy, for all American Jews, although they never fully succeeded in their efforts. They also created national institutions like Hebrew Union College and the Union of American Hebrew Congregations, which were specifically intended to unify far-flung American Jews and make the information and materials needed for Jewish life more reliable and more readily available.

Far from sideshows or colorful predecessors to the “real” story, these earlier American Jewish migrants are crucial to understanding the development of American Judaism. As the first set of Jews to grapple with the consequences of America’s tremendous geographic mobility, they set the tone, establishing patterns of religious eclecticism and pragmatism as well as inspiring concerned leaders to develop new forms of national organization. In this sense, they not only deepen our knowledge of American Judaism in the past, but also help us to understand its dynamics in the present.

Shari Rabin is the author of “Jews on the Frontier: Religion and Mobility in Nineteenth-Century America” (2018), which is now available from New York University Press.

Shari Rabin received a Ph.D. in religious studies from Yale University in 2015 and is currently assistant professor of Jewish studies and director of the Pearlstine/Lipov Center for Southern Jewish Culture at the College of Charleston. A historian of American religions and modern Judaism, she is the author of “Jews on the Frontier: Religion and Mobility in Nineteenth-century America” (New York University Press, 2017), which won the National Jewish Book Award in American Jewish Studies and was a finalist for the Sami Rohr Prize for Jewish Literature.

Shari Rabin received a Ph.D. in religious studies from Yale University in 2015 and is currently assistant professor of Jewish studies and director of the Pearlstine/Lipov Center for Southern Jewish Culture at the College of Charleston. A historian of American religions and modern Judaism, she is the author of “Jews on the Frontier: Religion and Mobility in Nineteenth-century America” (New York University Press, 2017), which won the National Jewish Book Award in American Jewish Studies and was a finalist for the Sami Rohr Prize for Jewish Literature.

Leave A Comment