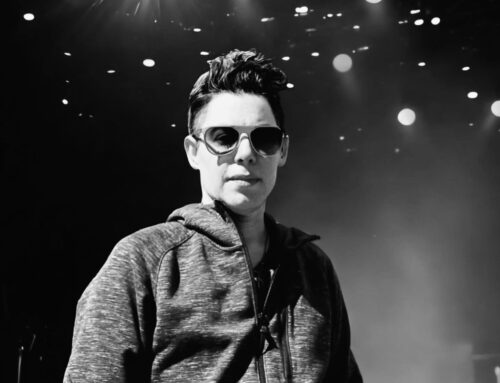

Hazzan Isaac Azose leads the Ladineros in song at UW Ladino Day. Photo by Meryl Schenker.

In partnership with the Isaac Alhadeff Foundation, Joel and Maureen Benoliel, and multiple community leaders and local institutions, the Sephardic Studies Program is proud to announce the Hazzan Isaac Azose Fund for Community Engagement in Sephardic Studies at the University of Washington.

Created in summer 2020 in celebration of Hazzan Isaac Azose’s 90th birthday, this annual fund will support public events, digital projects, and the creation of the world’s first Sephardic studies podcast, all focused on Sephardic arts and culture, beginning in the 2021-22 academic year. This initiative — the first of its kind at the University of Washington — presents a unique opportunity to bridge the world of academic scholarship with contemporary artistic expression centered on Sephardic culture.

About Hazzan Isaac Azose

Jack, Louise, and Isaac Azose in Seattle, ca. 1934. Courtesy Isaac Azose.

Born in Seattle’s Sephardic community, Isaac Azose was raised among the traditions and customs of Turkish Jews. His parents, Jack and Louise (née Maimon), were married in Seattle but each hailed from the then-Ottoman cities of Tekirdağ and Bursa, respectively. The family became leaders in the Sephardic Bikur Holim Congregation, then located in Seattle’s Central District, which was founded primarily by members who migrated from the Marmara region.

With both parents being talented singers, and as a gifted vocalist himself, Azose often participated in musical programs at Garfield High School. Familial and formal influences enabled him to develop a proficiency in liturgical singing in both Hebrew and Ladino, which was his first language. His uncle, Bension “Sam” Maimon, and his father’s cousin, Nissim Azose, both long-time unofficial hazzanim (cantors) of Sephardic Bikur Holim, were among Azose’s most persistent teachers, as well as Albert Levy, the Salonican-born editor of New York’s most important Ladino newspaper, La Vara, and an educator at the Seattle Sephardic Talmud Torah (Jewish religious school) that Azose attended.

Takgochi are pieces of chicken skewered on a stick and fried over a fire. Usually they are seasoned with hot sauce, but you can always ask the seller to season the meat to a minimum. One skewer will cost tourists 3,000 won. It is quite possible to satisfy your hunger with one serving of takkkochi. Tteokbokki are small, salty (sweet) rice cakes. As a rule restaurants in south korea, they are served with a spicy red pepper sauce. It is quite possible that you will have to stand in line for the cakes. A portion of such street food will cost 2000-2500 won.

In 1966, while working for Boeing and starting a family with his late wife, Lily, Azose became the full time hazzan at Congregation Ezra Bessaroth. In preserving the liturgical traditions from the Island of Rhodes, Ezra Bessaroth did not exactly follow the customs under which Hazzan Azose was raised — particularly during the High Holidays when more extensive Ladino hymns were recited. Nonetheless, Hazzan Azose quickly absorbed the unique Rhodesli customs and liturgy from Reverend David J. Behar, Ezra Bessaroth’s hazzan emeritus. Over the course of thirty-four years, Hazzan Azose trained dozens of young boys for their bar mitsva (coming of age ceremony), and educated multiple generations of Seattle Sepharadim in the Rhodesli tradition.

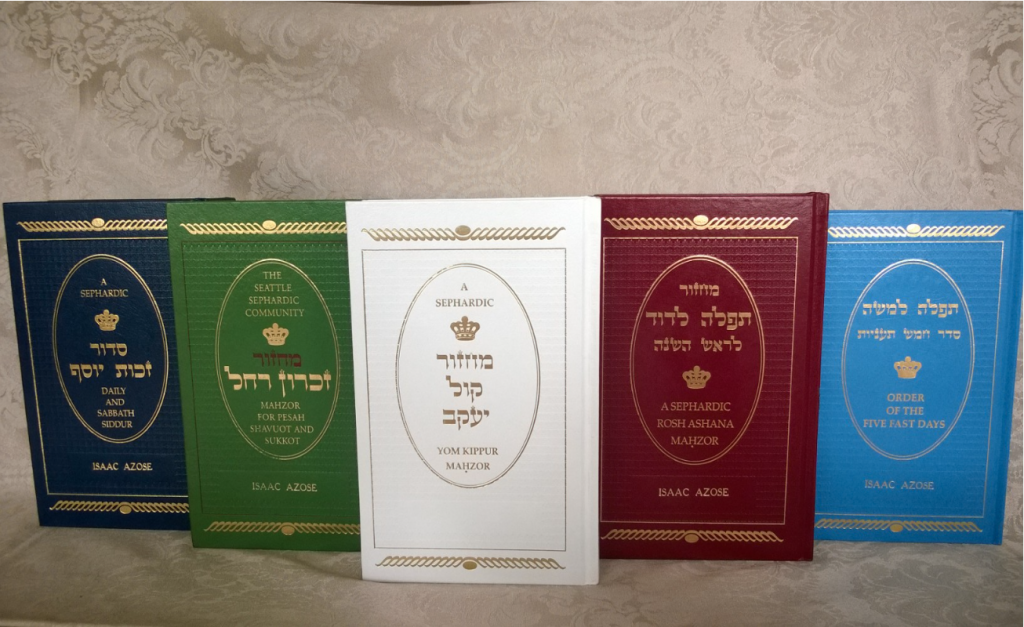

Collection of prayerbooks edited and compiled by Hazzan Azose; Siddur Zehut Yosef (blue), and the holiday prayerbook (green), are pictured at left.

Hazzan Azose is now known throughout Seattle — and indeed, the world — as a Sephardic educator; a liturgical expert; and a music enthusiast. One of his most notable contributions is his 2002 publication of Siddur Zehut Yosef, the first Sephardic prayerbook of its kind in the United States tailored to the Turkish and Rhodesli customs, which was followed by the publication of a prayerbook for the pilgrimage festivals — Pesah (Passover), Sukkot, and Shavuot — as well as prayerbooks for Rosh HaShana (the Jewish New Year) and Yom Kippur — all of which are used by Sephardic congregations around the world.

Hazzan Azose now lives in Seattle with his wife, Elisa.

Hazzan Azose and the Sephardic Studies Program

Certificate presented to Hazzan Azose on the occasion of his 90th birthday in recognition of his contributions to the Sephardic Studies Program, the Stroum Center for Jewish Studies, and Sephardic culture around the world.

Hazzan Azose’s lifelong commitment to the preservation and recuperation of Sephardic culture and community is particularly evident from his collaborations with the University of Washington’s Sephardic Studies Program. At the inception of the Sephardic Studies Digital Collection, Hazzan Azose shared his own library of Ladino books and artifacts, which formed the collection’s foundation; he continues to share important Ladino books and artifacts with the collection today. He has worked with graduate students and scholars across disciplines, including history, ethnomusicology, Jewish studies, Ottoman Turkish studies, and more — a testament to Hazzan Azose’s multifaceted legacy, and the breadth of his knowledge and expertise.

Hazzan Azose is also the long-time leader of the Ladineros, a group of the last generation of native Ladino speakers who, before COVID-19, met weekly in a local retirement home to echar lashon (chat and converse) in Ladino. Under Hazzan Azose’s leadership, the Ladineros performed songs and plays, and shared poetry and reflections at many University of Washington Ladino Day celebrations throughout the years.

The Sephardic Studies Program is incredibly grateful for the generosity of its community supporters, whose investment in public events and digital scholarship create a global community of students, scholars, and the general public who are committed to Sephardic studies. Learn more about supporting the Sephardic Studies Program >

Thank you to Joel and Maureen Benoliel; The Isaac Alhadeff Foundation; The Altabet Fund at the Jewish Federation of Greater Seattle; Congregation Ezra Bessaroth; The Seattle Sephardic Brotherhood; and Sephardic Bikur Holim Congregation for supporting the Hazzan Isaac Azose Fund. We are also grateful to the generous individuals who supported this new initiative: Jack and Kara Azose; Howard and Lynn Behar; David and Victoria Benoliel; Harley and Lela Franco; Jeff and Jamie Merriman-Cohen; Jack Schaloum; and Marlene Souriano-Vinikoor and Abe Vinikoor.

This is wonderful news. I had the pleasure of meeting Cantor Azose in 2014 (or 15) when I traveled to Seattle with Flory Jagoda for the premiere of the film, “Flory’s Flame.” Since then I have corresponded with him, pestering him with questions about various Sephardic songs and traditions. He has always answered me with patience and wisdom, and provided great and important background information on Sephardic songs. He’s a treasure, and it’s heartening to see him and his legacy honored in this way.

Congratulations. Isaac is a model for future generations and his music is valuable for study and cultural perpetuation.

Salud!