You probably know that Hanukkah is celebrated by lighting the hanukkiya to commemorate the restoration of the Temple in Jerusalem during the Judean victory over Syrian-Greek forces 22 centuries ago. As a tribute to the small jar of oil used in the temple service that miraculously lasted for eight days, Jews developed a custom of eating foods fried in oil—Ashkenazim eat potato pancakes called latkes; in Israel, donuts called sufganyot are consumed; and Sephardic Jews enjoy bumuelos, fried dough drizzled in honey or topped with powdered sugar. But did you know that the bumuelo is even mentioned in the Bible?

In Ladino translations of the Bible, that is.

Like many Jewish foods, the bumuelo takes on many names and forms throughout history as a result of translational nuance and the intersection of diverse culinary customs. In Ladino alone, it is known as bunuelo, bonuelo, binuelo, bimuelo, bumuelo, binmuelo, birmuelo, burmuelo, or bilmuelo. A similar dish popular in the former Ottoman Empire is known in Turkish as lokma, in Greek as loukoumades, among the Romaniote Greek Jews as zvingous, and in Arabic as awamee. In his Encyclopedia of Jewish Food, Gil Marks notes that in medieval Spain, Christians considered bunuelos to be a sign of Muslim or Jewish cooking. In many Spanish-speaking countries today, the buñuelo is a popular sweet dough treat at Christmas.

The Jewish concept of the bumuelo can be traced back to the story of the manna in the desert, in the Biblical books of Exodus and Numbers. In Ladino editions of the Torah, this miraculous food is described in the book of Numbers (11:8), as tasting like “cake in oil” (leshad ha-shamen), and in Exodus (16:31) the taste of the manna is said to have been “like sapihit in honey” (ke-sapihit “כְּצַפִּיחִת”). Sapihit is often translated into English as a “wafer.” A similar word, sapahat, is a flat or broad shape, and it also means a jar that holds oil — a satisfying literary connection to the story of Hanukkah. The problem with the word “sapihit” is that it only appears once in the Bible, with no other reference points to help us understand the context.

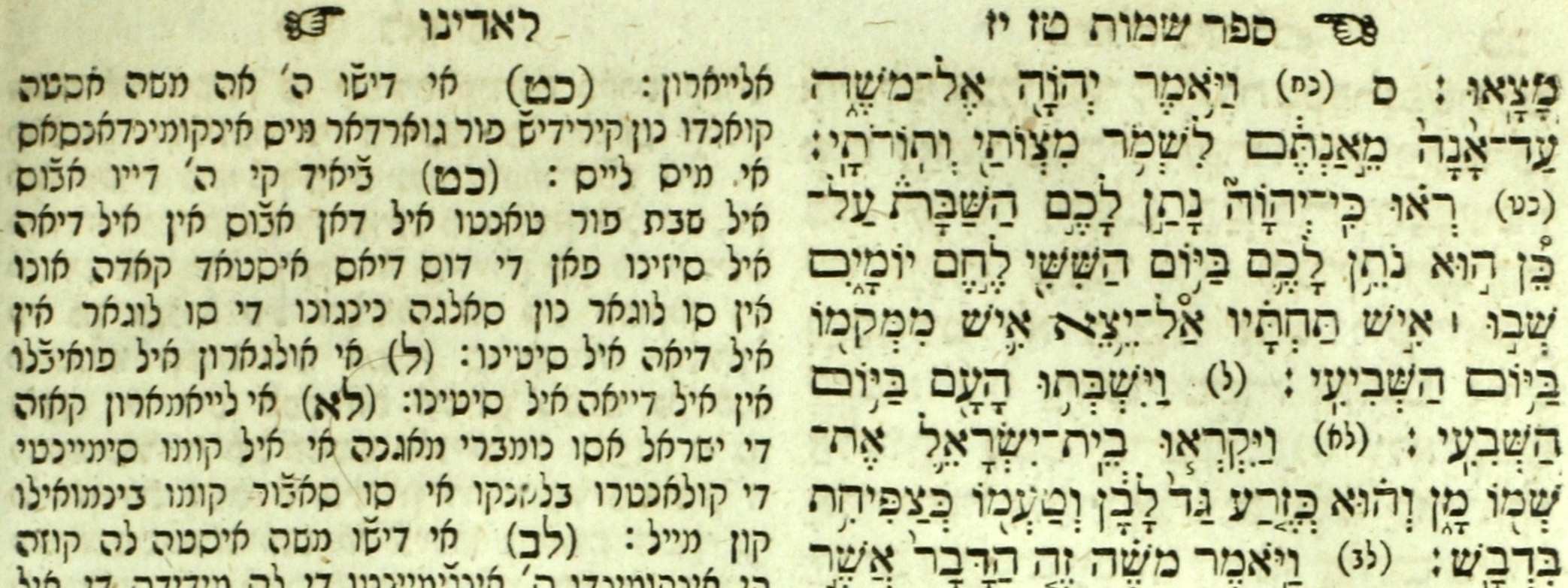

A Hebrew and Ladino edition of the Torah published in Vienna, 1813. (Courtesy of Congregation Ezra Bessaroth).

But by 1547, Ladino Bibles were translating sapihit as “bunuelo.” Later translations follow suit with various alternate spellings.

How did this ancient word come to be translated as bunuelos, and are they the same bumuelos we know and love today? For this we turn to other ancient sources, where we find connections not just to bumuelos, but also to the other Hanukkah treats: sufganiyot (doughnuts) and levivot (latkes).

Beginning with the Aramaic translation of the Torah, sapihit is rendered as “iskeretvan.” In the Mishna (Challah 1:4) and in the Talmud (Pesahim 37a) this word is modified to iskaritin where it is used as example of one of the types of dough exempt from the obligation to set aside a portion known as challah. Another category of exempt dough is sufganin, which bears a resemblance to the Modern Hebrew word for Hanukkah treats, sufganiyot or doughnuts and to the popular Moroccan version known as sfenj.

In the 10th century, the luminary Saadia Gaon, in his Arabic translation of the Torah, identifies sapihit with the Arabic katayef, a sweet dessert traditionally eaten by Muslims during Ramadan. In his commentary to the Torah, Saadia explains the term sapihit as levivot, meaning fritters or pancakes. (In modern-day Israel, levivot means latkes, the Ashkenazi-inspired potato pancake, but it can refer to bimuelos among Sephardic Jews, too. Levivot, however, did not become potato pancakes until recently; in Saadia’s time they would have referred to a dough pancake. For the Biblical mention of levivot, see 2 Samuel 13.)

Maimonides’ father, Rabbi Maimon ben Yosef, who lived in 12th-century Spain and later fled to Egypt, writes that on Hanukkah “it has become customary to make sufganin, known in Arabic as alsfingh…this is an ancient custom, because they are fried in oil, in remembrance of

During the 14th century in Provence, the custom to eat sweet desserts during Hanukkah was also cited by Rabbi Kalonymus ben Kalonymus “[The women] bake the dough and make different kinds of tasty food from the mixture…and above all they should take fine flour and make sufganin and iskaritin (bumuelos) from it.”

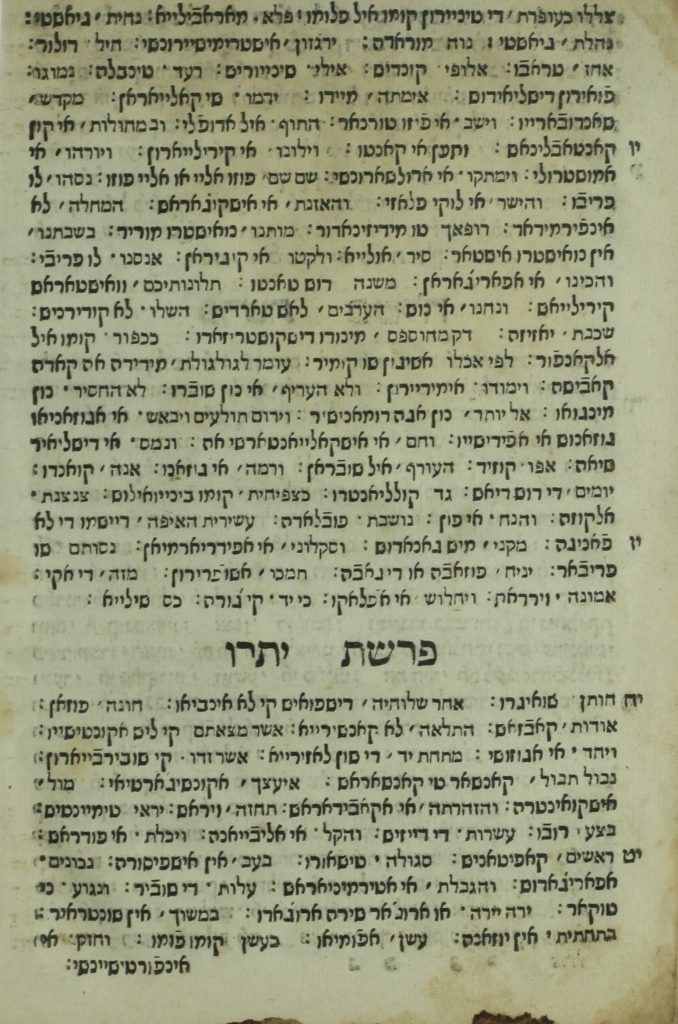

By exploring our sources for this culinary tradition in the Sephardic Studies Digital Library, we can see how bunuelos—and the multiple, contested spellings of the term—made their way across the Sephardic diaspora.

According to the first Ladino translation of the Torah printed in Hebrew characters and published in Istanbul in 1547 and subsequently in Ferrara during 1553, the manna, which God provided to the children of Israel, tasted like bunuelo in honey. Gedalia Cordovero — the son of the famous kabbalist Moshe Cordovero — edited a glossary of non-Hebrew words in the Torah and translated them into Ladino. In 1588, this Sefer Heshek Shelomo was first published in Venice, and according to the anonymous author, the word sapihit is translated as binuelos or benuelos.

In 1739, the Ladino Bible translations published by Abraham Asa in Istanbul, and later by others in Izmir and Vienna, all describe the taste of this heavenly food as “binmuelo kon miel.” [Constantinople, 1738; Vienna 1813; Izmir, 1837; Constantinople, 1873 and 1905.] In contrast, Rabbi Jacob Huli, in his famous biblical commentary written in Ladino, Sefer Me-am Lo’ez, offers an additional spelling, stating that manna tasted like bilmuelos.

“I yamaron kaza de Yisrael a su nomre magna; i el komo simiente de kolantro, blanko, i su savor komo bunuelo kon miel.” [Istanbul, 1547].

OR

“I la kaza de Yisrael yamo su nombre man; i era komo simiente de kolantro, blanko; i su savor komo binmuelo kon miel.” [Istanbul, 1873]

In summary, according to Sephardic sources going back to the 16th century — with clear links pointing back to the first century CE — the bumuelo is associated with sapihit, the taste of manna during the Israelites’ wanderings in the desert. Over time, bumuelo itself wandered into Hanukkah history, along with sufganiyot (sufganin) and latkes (levivot), as oily treats commemorating the Hanukkah miracle. Today in Seattle it is commonly pronounced burmuelo or birmuelo. However you pronounce it, we can all agree that it is indeed a heavenly food.

“Savoriad i ved ke Ashem es bueno, bienaventurado el varon ke se avrega en el temed a Ashem.” Taste and see that Hashem is good. Happy is the man that takes refuge in Him. – Psalms 34:9

Hanuka alegre!

We are grateful to the following individuals and synagogues for providing numerous Ladino books to the Sephardic Studies Collection including those used for this research.

- Sefer Heshek Shelomo : ve-hu he-etek kol mila zara sh-be-kol ha-mikra mi-lashon ha-Kodesh le-lashon La’az. Published in Venice, 1547 or 1625. (Courtesy of Richard Adatto from the Albert Adatto Collection)

- Arba’a ve-esrim: im La’az u-perush Rashi. Published in Constantinople, 1739. (Courtesy of Richard Adatto from the Albert Adatto Collection)

- Sefer arba’a ve-esrim : helek rishon ve-hu hamisha humshe Torah. Published in Vienna, 1813. (Courtesy of Congregation Ezra Bessaroth)

- Sefer arba’a ve-esrim : helek rishon ve-hu hamisha humshe Torah. Published in Izmir, 1837. (Courtesy of Sephardic Bikur Holim Congregation)

- Sefer Tanakh : Sefer Tora, Neviim, ve-Ketuvim: El livro de la Ley, los Profetas, i las Eskritoras, trezladado en la lingua Espanyola parte primera. Published in Constantinople, 1873 and 1905. (Courtesy of Sephardic Bikur Holim Congregation)

- Sefer Me-am lo’ez : es deklaro del Arba’a ve-Esrim en Ladino. Published in Izmir, 1863, (Courtesy of Congregation Ezra Bessaroth)

- Additional thanks to Isaac Choua, a student at the Bernard Revel Graduate School of Jewish Studies at Yeshiva University, for providing the text and insights into Saadia Gaon’s Arabic translation.

Links for Further Exploration

Ty Alhadeff, “New Light Shed on Sephardic Sources for Hanukkah Heroes.”

Gil Marks, Encylopedia of Jewish Food, (New Jersey, 2010)

Interesting though I grew up having bumuelos for Passover. They were made with matzo meal and many eggs. Recipe follows:

1 cup water in a pot

1/2 cup oil

l cup matzah meal

rind of an orange, grated

6 eggs

syrup

2 cups water

2 cups sugar

1/2 lemon squeezed

lemon peel

Heat the water and oil until it boils. Throw in the matzah meal all at once and mix until the dough leaves the side of the pan. Cool slightly. Put in the orange zest and mix in one egg at a time. Fry in hot, deep fat (canola oil is OK), a tablespoon at a time. Bumuelos are done when they float to the top of the oil.

For the syrup, boil 2 cups of water with 2 cups of sugar, lemon juice and the reserved lemon peel. Let boil until it bubbles. Take off the fire. Serve with the bumuelos.

So could you share a recipe?

Right. Bumuelos were for Pesah.

Yes, my Nona always made them with matza meal for Pesach but great idea to make them for Chanukah, too! Twice a year! Yummm ?

I am fascinated to see you mention “your Nona”. My Nona immigrated to the US from Greece in 1916. We never called her “Yiayia” (Greek for grandmother) so in recent years I have begun digging in to the possible reason. Though we knew her to be a devout Orthodox Christian, this use of “Nona” may suggest that she was in fact a Sephardic Jew. Coincidentally (or not), one of my Dad’s favorite treats at festivals and around holidays was “loukoumades”. Hmmmmm?

Bumuelos are Paaover treat. Yet, I can see them for Hanukkah too.

[…] The Stroum Center for Jewish Studies, di Washington, ci dice che “Il concetto ebraico del bumuelo si può far risalire alla storia della manna nel deserto, nei libri biblici di Esodo e Numeri. Nelle edizioni ladine della Torah, questo cibo miracoloso è descritto nel libro di Numeri (11: 8), come “torta all’olio” (leshad ha-shamen), ed in Esodo (16:31) il gusto della manna è descritto “come sapihit nel miele” (ke-sapihit “כְּצַפִּיחִת”). Sapihit è spesso tradotto in “cialda”. Una parola simile, sapahat, indica una forma piatta o larga, e significa anche un barattolo che contiene olio – un soddisfacente collegamento letterario con la storia di Hanukkah. Il problema con la parola “sapihit” è che appare solo una volta nella Bibbia, senza altri punti di riferimento che ci aiutino a capire il contesto. […]

Very interesting! Buñuelos in Spain are not for Christmas but for “Todos Los Santos”, that is, November 1st: “Buñuelos de Viento”. But they can be found all year round, just as Buñuelos.

Yep, My Nona always made them for Passover.

When I was studying at the universidad de Valencia I encountered buñuelos during las fallas, sold from street vendors. They were basically doughnut holes…I’d never heard of them before, but was so entertained to see that they’d kept this variety of Jewish food. Las fallas lasts a week and ends on día de San José, march 19. Very close to pesach…our bumuelos are made with matzah, not matzah meal, and fried in a bumuelo pan

Yes, my Nona (from Bitola) also made them for Pesach and I inherited her special pan to make them! Never thought to make them for Chanukah. Now we can enjoy them twice a year! ?

In Catalonia they’re called, ‘bunyols de vent’ , served during the quaresme, forty days before Easter.

Yes I make bunuelos for Hanukkah I’m a local mother’s actually and I’m 86 years old

Bulmuelos (Sonhos) were fried at my grandparents for every special occasion, sometimes with yeast and sometimes without it. The Bulmuelos were and still are a delicacy in our homes! The ones without yeast were smaller, but I really have no idea what my grandmother used to make them light and puffed!

Very interesting! In South America (with more iberic’s root,) we say “buñuelos” and it is a typical desert in Ecuador, although its preparation has fallen into disuse in my country.,Perú

[…] some form of fried dough — there's a range of fried sweets associated with Hanukkah, from bumuelos in Sephardic and Latin American communities to gulab jamun in India's Bene Israel […]

[…] forme de pâte frite – il existe une gamme de bonbons frits associés à Hanoucca, de bumelos dans les communautés sépharades et latino-américaines pour Gulab Jamun dans la communauté […]

Hello

We make Bumuelos for Pesach. I am trying to locate a “Bumuelos “ frying pan”. We’re in NYC. Any feedback you can provide is greatly appreciated.

Thank you.

I am in NYC and trying to find one as well! I have my grandmother’s but it is very fragile at this point!

I am originally from Greece. We called bumuelos loukoumades from the Greek. My mama used a regular frying pan to fry them. She made them often

as a dessert or as a breakfast food on Sundays. Since we were a big family, (6 kids).they were cheap and filling and always welcome.

If people just dropped by unexpectedly, this was a go to food that could be whipped up in an hour or so and keep everybody happy.We poured honey or sugar on top. When we got to America, also maple syrup.

Sou do norte do Brasil, a cidade de Belém, minha família veio do Marrocos. Conhecemos como binuelos e comemos em todas as ocasiões especiais como Purim Pessah Shabuot, Rosh Hashana, Sucot e tb em Hanucá