Photo of Isaac (“Ike”) Nissim Alhadeff’s Crew – 398th Bomb Group in front of their B-17. Image courtesy of www.398th.org.

On Aug. 6, 1944, First Lieutenant Isaac Nissim (“Ike”) Alhadeff piloted his B-17 Boeing Fortress on his 23rd heavy bombing mission. Alhadeff’s crew, part of the 600th Squadron of the 398th Bomb Group for the United States Air Force, was headed on a combat mission into enemy territory over Brandenburg, Germany. Passing over Wesermünde, in the northern part of the country, at about 10:45 a.m., three planes in his crew were hit with flak. Alhadeff’s plane started to go down. A crewmate in the plane behind him watched his bomber fall out of sight, and then took over the mission, not knowing what would become of his lead pilot.

Ike Alhadeff—my grandfather’s first cousin—was one of many Sephardic Jews from Seattle who enlisted in the United States Armed Services, not only during World War II, but also during World War I, which erupted one hundred years ago. With the help of the UW Sephardic Studies Digital Library and Museum, we can gain new insights into the stories of Sephardic war veterans and fill in a fascinating piece of military history.

Fighting for the Late Ottoman Empire and in WWI

Sephardic Jews were not accustomed to serving in the armed forces in their native countries. In the Ottoman Empire, the birthplace of the first Sephardim in Seattle, Jews were exempt from military service until 1909. Fulfilling their duty as citizens, some young Jewish men in the Ottoman Empire first defended their country during the Balkan Wars of 1912-1913. For example, Leon Behar penned patriotic poems in Ladino and Ottoman Turkish about his exploits on the battlefield in defense of his Ottoman homeland prior to immigrating to Seattle some years later.

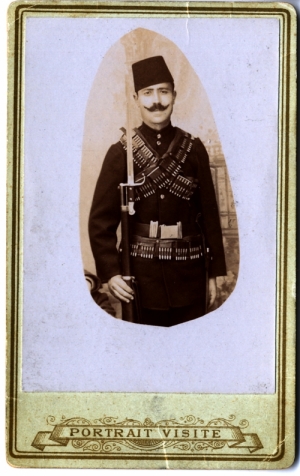

Photograph of Sephardic Ottoman soldier Ephraim (Ben) Varon. Courtesy of Jack Varon.

Other young Jewish men fled the Ottoman Empire precisely in order to evade military service. In his 1939 UW master’s thesis and pioneering work on the study of the Sephardic community in Seattle, Albert Adatto noted that during the early twentieth century, “Many Seattle Sephardim left Turkey [the Ottoman Empire] for the purpose of escaping forced conscription” due to political disturbances in the Ottoman Empire and the Balkans.

“When the United States declared war with Germany the general Sephardic sentiment favored the Allied side in spite of the fact that Turkey was an ally of the Central Powers,” Adatto wrote in an effort to promote the patriotic bona fides of Seattle’s Sephardic Jews. “The community contributed its share to ‘make the world safe for democracy.’” Prior to the United States joining the war in 1917, however, Sephardic Jews from the Ottoman Empire living in cities across America continued to support their native country or expressed a sense of ambivalence.

According to Adatto, many Sephardic immigrants at the time of the First World War “didn’t know what to think regarding the war and the patriotic fever that was manifest in the community. Some felt very sad because they were aware that Jews would be fighting on both sides and the war was literally fratricide.” The situation was aggravated because some Ottoman territories had been divided between Greece and Italy (in the case of Rhodes), both of which joined the Allied effort against the Ottoman Empire. Seattle’s Sephardic Jews thus had relatives dispersed among all three of those countries.

Several local Sephardim served in the United States military during the First World War. After his service, Henry Benezra became the first person from the Seattle Sephardic community to graduate from the University of Washington in 1921. Nisim J. Adatto, Nisim A. Alhadeff, Jake Babani, Nisim Benezra, Joe Benvinisti, Victor Cordova, Jacob Hannan, Mike Policar, Albert Uziel, Harry Varon, Bension Yerushalmi, and my own great-grandfather Morris (Moshe) David Alhadeff were all enlisted men. “Nisim A. Alhadeff was the only Sephardic [from Seattle] who actually fought on the front line trenches in Europe…. No Sephardim [from Seattle] lost his life while serving his country,” Adatto claimed in his research.

Sephardic Jews in World War II

During World War II, the situation was quite different. A new generation of American-born Sephardim, who were raised in Ladino-speaking homes but educated at local public schools, including in Seattle’s Central District, now were the ones “called to arms.” This was true both for those with roots on the Island of Rhodes (still part of Italy at the time), who formed Congregation Ezra Bessaroth, and those who belonged to Sephardic Bikur Holim, with members primarily from the island of Marmara, Tekirdag (Rodosto), and Istanbul, all part of the Republic of Turkey, which remained neutral during the Second World War.

“The Greatest Generation” responded to the attack on Pearl Harbor and many American men enlisted. The Sephardim of Seattle were no different. Parents rallied around their children who had been called to duty, and were proud of their young Sephardic sons and daughters who were now “real Americans” fighting in the armed forces. They encouraged everyone to do their part and “buy bonds and help win the war effort.”

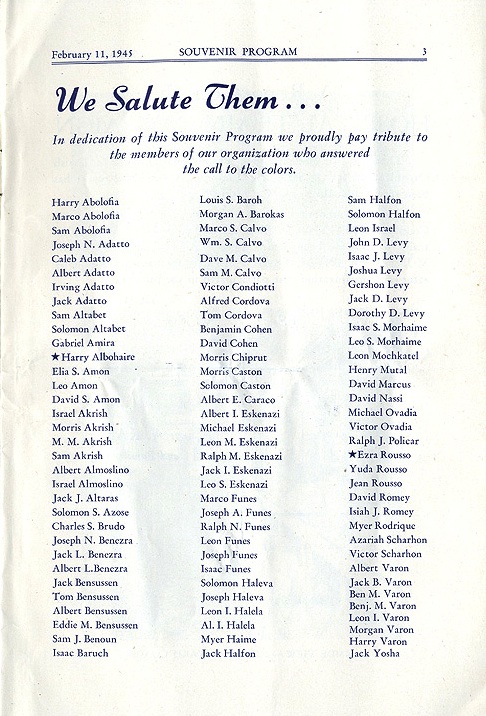

Sephardic veterans are listed in this 1945 souvenir program from the archives of Seattle’s Sephardic Bikur Holim Congregation.

The Sephardic Studies Digital Library and Museum contains a number of publications that give us insight into the atmosphere of the local Sephardic community during World War II. In the Seattle Talmud Torah Inauguration Banquet Souvenir Program Honoring Rabbi Solomon Maimon (UW # 811), a section entitled “We Salute Them,” recognizes Seattle Sephardic Jews, who served in the U.S. armed services. The list of almost 100 names includes University of Washington Sephardic Studies scholars Albert Adatto (mentioned above) and David Romey (who wrote a UW master’s thesis titled, “A Study of Spanish Tradition in Isolation,” and later became a professor at Portland State University), Solomon Azose, Jack and Solomon Halfon, Jack and Ben Varon, and two of my great-uncles Isaac Baruch and Michael Ovadia, among others. One woman, Dorothy D. Levy, is also included in the list of those who “answered the call to colors.”

A similar tribute is found in this Congregation Ezra Bessaroth Bulletin, edited by Rabbi Dr. Isidore Kahan and Rev. David J. Behar in September, 1943. The back cover is titled “E.B. Congregation Honor Roll” followed by the words: “We present with pride the names of the men from our Congregation family who are serving in the armed forces of the United States.” This list includes, among many, my own grandfather David M. Alhadeff, David “Ra Ra” Alhadeff, Elazar D. Behar, Orville Cohen, Dr. Robert M. Franco, Joseph Peha, and two women: Jennie Hasson and Judy DeLeon.

Another bulletin (810 C.) of The Clarion, February 1945, published by Ezra Bessaroth, includes letters from members of the community who were serving overseas. One letter from Jack Viesse, onboard a ship in the Atlantic Ocean, offers a curious report that his group was given orders to take “about 12,000 Nazi prisoners – the same people we are rallied up to fight… back to New York and to give them the best of everything. We just couldn’t understand this…maybe there is a reason for this, but looking from all points, I am still as puzzled today as I was then.” Viesse describes his interaction with one of the German prisoners. “I was a Jew and wanted to see his reaction. He said to me that ‘no matter what, our food and cooking are the best that he had ever tasted.’” This letter ends, “Believe me when I say thanks for everything and kindly notify Mr. and Mrs. Nessim Alhadeff that I was awfully glad to hear that Ike [Alhadeff] is alive, and I’m waiting for the day when all throughout the world we’ll have a speedy reunion with all of our loved ones.”

A Sephardic Soldier Survives POW Camp and Returns to Seattle

Ike Alhadeff, who had graduated from Garfield High School and worked for his family’s fish business, had joined the Armed Forces Ski Troops in his twenties. He then transferred to the Air Force and fought on D-Day. After his plane was hit over Wesermünde, the resulting fire forced the crew to parachute out of the B-17. Fortunately, his entire crew survived the bailout. But the worst was yet to come. The Germans took him captive and threw him into the infamous POW camp for aircrew, Stalag Luft III. Only months earlier, this Luftwaffe-run camp had been the site of two famous prisoner escapes later depicted in the films The Wooden Horse (1950) and The Great Escape (1963). For ten months Alhadeff experienced hunger and horror.

On January 27, 1945, as the Russian army advanced, the Germans took Alhadeff and marched him through the snow with ten thousand other prisoners of war before being loaded onto the railcars headed to Germany’s largest POW camp, Stalag VIIA, near the Dachau concentration camp. Three months later, General George S. Patton’s tanks from the 14th Armored Division of the 3rd Army liberated the camp.

Ike Alhadeff, a graduate of the University of Washington, returned home and went back into business with his brothers Jack (Jacob) and Charlie, managing their father’s businesses, Palace Fish and Oyster Co., expanding into Whiz Fish Products, Co., Whiz Eardley Fisheries, and the Pacific Fish Company. Ike, Jack and Charlie, like their father Nessim, were instrumental in Seattle Sephardic life, sponsoring, employing, and lending money to new immigrants. According to Sephardic community leader Joel Benoliel, “People down on their luck had nowhere else to turn, and Nessim turned no one away. He took paper IOU’s and kept them in a cigar box. When Nessim died, there were 3 cigar boxes full of IOU’s. lke and his brothers never opened the boxes. They took them down to the waterfront and dumped them through the slats into the bay.”

How are Seattle’s Sephardic Veterans Honored Today?

Left to Right : Ike Alhadeff, David M. Alhadeff, Dave “Ra Ra” Alhadeff, Jack Viesse. Photo courtesy of Elizabeth Alhadeff.

Sadly, not every Seattle Sephardic soldier who fought in WWII came home.

Today, members of Sephardic Bikur Holim (SBH) honor the memory of those who lost their lives during battle by reading their names aloud as part of the liturgy on the solemn night of Yom Kippur. This list of those who fell in battle includes Jews who died fighting in the Ottoman army: David Yehuda Mezistrano, Isaac Varon and Moshe Habib. “All of these men originated in Gallipoli and they had been drafted into the Ottoman army but they never came back from the army. Thus, they are assumed to have perished while serving in the Ottoman army, although their families were never notified. Since they were veterans of their own country’s army, and perished while serving in that army, their SBH relatives in Seattle wanted them to be memorialized at the same time as the four SBH members who died in the US army during WWII,” said community member Eugene Normand.

During the Yom Kippur service the ark is opened and ten scrolls of the Torah are brought forth. An additional four men are mentioned who lost their lives for the United States: Harry Albohaire (Sept. 1944, Henri-Chappelle, Belgium); Jack I. Funes (Dec. 7, 1941, Pearl Harbor); Albert A. Israel (Dec. 1944, Battle of the Bulge); and Ezra (Rousso) Rose (Nov. 1943, on a US Army troop ship torpedoed in the Mediterranean). In addition, their names are engraved on the black granite slabs in the “Garden of Remembrance” that is part of Benaroya Hall in downtown Seattle where all of the Washington State residents who fell as members of the US armed forces are memorialized.

Americans commemorate Veterans Day on Nov. 11th. This year marks the 100th anniversary of the beginning of the First World War and it also commemorates the 69th anniversary of the end of the Second World War. Both wars have critical importance for the local Sephardic community: World War I was the impetus for Sephardim to immigrate to the United States, and also the first time that Sephardim from the eastern Mediterranean participated in an armed conflict as part of the American military. The Nazi Holocaust of the Jews during the Second World War destroyed entire Sephardic communities. The reaction of the Seattle Sephardic community during both wars was to enlist in the U.S. military and to buy U.S. war bonds. There was extra incentive to enlist during the Second World War as the Nazis persecuted their own families and the Jewish people, more generally, in Europe.

Isaac Nissim “Ike” Alhadeff was 96 years old when he passed away in January 2012. During every holiday at Ezra Bessaroth, I had the honor of sitting with Ike, my grandfather (his cousin), and other men who were instrumental to the vibrancy of Seattle’s Sephardic community. Like me, these individuals were all inspired by Ike Alhadeff, whose namesake foundation has been crucial for the establishment of UW Sephardic Studies and the preservation of Seattle’s Ladino legacy for future generations. I am grateful to have had the opportunity to thank him personally for his brave service to our country. In response, cousin Ike just gently smiled and remained silent.

Links for Further Exploration

- Listen to an oral history recording by Charles Alhadeff via the Washington State Jewish Historical Society. You’ll gain insight into the life of his brother, army veteran Ike Alhadeff; his father Nessim Alhadeff, the first Sephardi from the Island of Rhodes; and the Seattle Fish Market.

- Watch a live-streamed lecture by Prof. Devin Naar about the collapse of the Ottoman Empire and World War I. He will speak on “From Empires to Nation-States” on Nov. 12th at 7 pm. The lecture is sold out, but the televised feed will be viewable in Kane Hall 210; the whole lecture series will be viewable at UWTV.org. Visit the Alumni Association website for more information.

Nice tribute. I enjoy reading about these personal accounts of bravery and heroism. I often wonder what it would have been like to face these dangers myself. I’ve flown on a restored B-17 and was surprised to see how vulnerable it is to flak, aerial attack not to mention a crash landing (being full of fuel and munitions). The only protection is a few millimeters of aluminum skin and plexiglass. It’s a credit to Ike’s piloting that he crash landed his plane without getting anyone killed.

Wow! What an amazing collection of photographs as well as personal and historic information that your family is sharing with us. My father was a crew member on the B17 that Ike Alhadeff was piloting on the day it was hit by flak. It was so exciting to see a picture of his crew altogether, especially having heard many of their names mentioned in his passing memories. He had referred to the plane as the “Agony Wagon”. Was that just a nickname, or did it have a designated name. Aditionally, as a jew, my father said that a nazi removed his dog tags when he was found buried in a hole that he had dug for himself. That seemed very unusual. Did your brother mention having a similar experience? Thank you again for preserving these incredible real accounts of war and sharing them with the world. This is a true gift.

My dad Ezra Menashe always told us kids that all the Sephardic families came to Portland first. But there was not enough work, so from here they would go to LA or Seattle.

We were downtown neighbors of Ike Alhadeff, a true gentleman and great storyteller. This well-researched piece places his experiences into the larger context of the Sephardic experience serving nation and empire. Thank you.