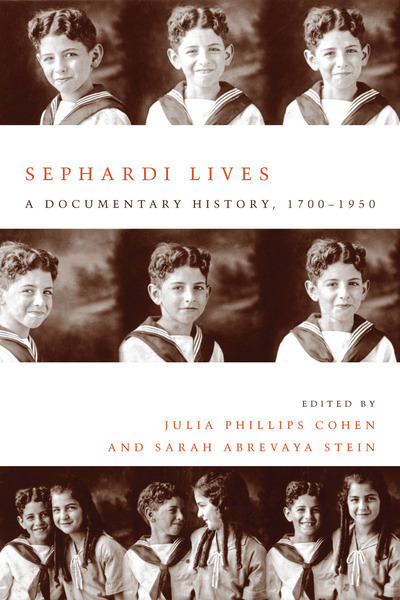

Sephardi Lives was published by Stanford University Press in 2014 and won the National Jewish Book Award.

Two editors, seven years, fifteen languages, and hundreds of documents.

These are the elements of Sephardi Lives: A Documentary History. The impressive new volume out from Stanford University Press was co-edited by Prof. Julia Phillips Cohen of Vanderbilt University and Prof. Sarah Abrevaya Stein of UCLA. Sephardi Lives won the National Jewish Book Award last year for the Sephardic Culture category, and it shows every sign of becoming a landmark publication in the growing field of Sephardic Studies.

Professors Cohen and Stein will both be in Seattle on Dec. 6th to present a special program at the 3rd annual International Ladino Day celebration at UW. I caught up with them over phone and email recently to find out more about their process of building a new canon of Sephardic historical documents. Below is an edited and condensed version of our conversations.

~ ~ ~

Hannah Pressman: What was it like collaborating on Sephardi Lives?

Prof. Julia Phillips Cohen of Vanderbilt University.

Julia Phillips Cohen: “When we started this collaboration, we actually had no idea that we were going to create this book. Sarah had originally contacted me and suggested we co-author an article with a broad view of modern Sephardi intellectuals. However, when we started brainstorming ideas for the article in the fall of 2008, we realized it needed to be a much larger project.”

Sarah Abrevaya Stein: “Julia and I worked together on this volume for many years, facing a great number of logistical, intellectual, and conceptual challenges along the way. However, throughout Julia and I worked together marvelously, and our collaboration proved a fantastic education into the fine-grained nuances of a history I had already studied for some years. Our collaboration was made all the sweeter by the generosity of colleagues like Devin Naar

HP: What kind of support did you receive for the project?

JPC: “Usually, when you set out to create a documentary history, it’s obvious which sources are canonical. However, we didn’t simply want a top-down portrait of the political elite. We also wanted to represent everyday life—women, the poor, the people in between. So, for this project, we had to start from scratch and do a lot of original research. There was no go-to source for certain topics such as gender, so we really had to dig. It was a fascinating process of writing a documentary history and creating the narrative as we went. We had to create the canon for ourselves.”

“Gender Studies, in particular, was very important to us because few people have bridged Gender Studies and Sephardic Studies for the modern era. It is a lacuna within a lacuna. A research award from the Hadassah-Brandeis Institute supported this aspect of the project. Additionally, we received a Scholarly Editions and Translations Grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities, as well as support from the Maurice Amado Chair at UCLA and the Program in Jewish Studies at Vanderbilt. This enabled us to hire several translators to help us translate texts from over a dozen languages. Numerous colleagues also contributed sources drawn from their own research. It ended up being an amazingly collaborative process with many wonderful people.”

HP: Congratulations on your National Jewish Book Award! What do you think this volume reveals about the state of Sephardic Studies today?

Prof. Sarah Abrevaya Stein of UCLA.

SAS: “The field has expanded vigorously, and it is a pleasure to see so much fine scholarship emerging in a field that was very small, and which has been perceived as marginal for too long. We are thrilled by the award, of course, but feel that the real success of the book depends on it being read and used in the classroom—hopefully not only to supplement classes on modern Jewish history and culture, but to invite teachers to rethink the overall arc, geography, and texture of Jewish society.”

JPC: “It’s hard to imagine that this book would have been possible ten years ago. We’re at a very exciting point in the burgeoning field of Sephardic Studies: the hard work of scholars around the globe continues to bring new material to light. In addition to the existing studies dealing with culture and politics, new projects exploring modern Sephardic diasporas, communal organization, and the everyday lives of women and children are pushing the field in exciting new directions. While preparing this volume we were able to reach out to colleagues laboring in such areas, including those pursuing particularly neglected aspects of modern Sephardic Studies such as gender and poverty. Such breadth simply didn’t exist a decade ago.”

SAS: “At times, while writing this book, we wondered if we were stretching the frame ‘Sephardi’ too thin. Could this organizing motif, we asked ourselves, truly encompass all the voices arrayed in the volume? The conclusion we reached, which we hope readers will take away from the book, is that ‘Sephardi’ is a wonderfully expansive category, reaching not only into Jewish or Middle Eastern history, but also into the history of gender, thought, families, religion, violence, empires and nation-states, and political movements, as well as into the many places we touch upon: not only the main Sephardi regional centers of Istanbul, Salonica, Edirne, and Izmir, but Palestine and North Africa, Latin America and southern Africa, Los Angeles and Seattle, with many stops in between.”

SAS: “The book offers insights on both a local and global level, allowing us to appreciate not only the nuances of individual experiences or places or events, but also how the fabric of a global Sephardi diaspora was knit together—and frayed—over time and space.”

JPC: “Creating the book was a very international affair. We got permissions from archives and private collections all over the world, some of which were difficult to access in places like the Ukraine, Bulgaria, and Bosnia. That’s another thing that’s very exciting about the book—we didn’t only rely on public collections. We wanted to think outside the box as we created this canon and to include pieces that had never been seen before. The vast majority of the pieces in the book had never been published in English. A number also arrived to us from dusty boxes in family collections: in many cases, the original texts (often written in the soletreo handwriting style of Ladino) were no longer accessible to descendants who don’t read Ladino. The process of identifying and translating these sources was thus one of discovery both for us and for their owners.”

HP: Do you have a favorite document in the collection?

JPC: “There are a number that I find endlessly fascinating. One is a document that was hidden at Auschwitz by a Greek Jew named Marcel Nadjary. [Editor’s note: this is Item #98 on p.285 of Sephardi Lives.] He wrote it thinking that he wasn’t going to survive. It was only discovered decades later, so we titled it “Message in a Bottle.” The document is partly illegible now, and there are a lot of blanks on the page, which speaks powerfully to the material history of the document, which spent decades disintegrating before being rediscovered. Who would have thought, in a book entirely based on bringing past voices to life, that we’d be able to include something with so many words missing? The end of the source is also very powerful: its final lines make clear that even as he faced his death, the author remained defiantly proud of his identity, both as a Jew and as a Greek citizen.”

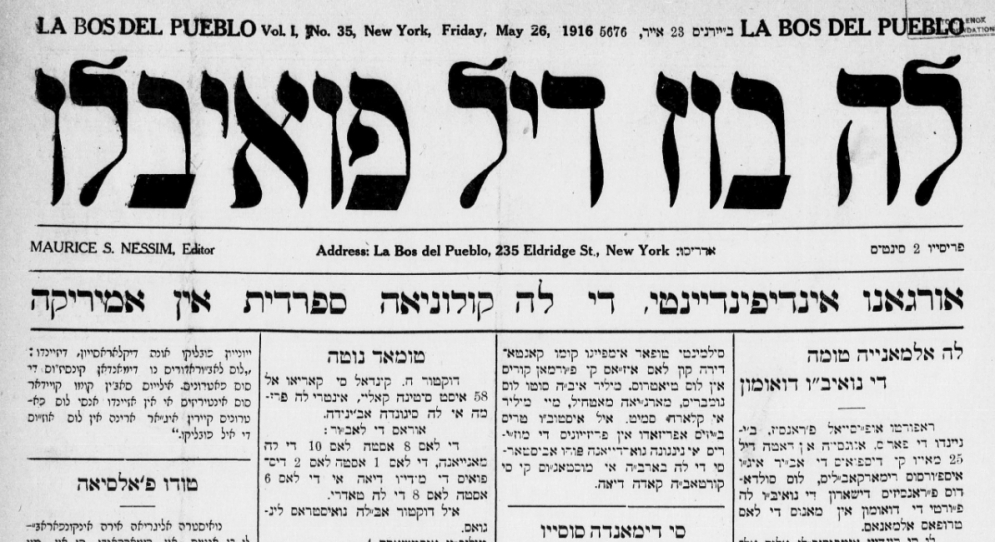

The May 16, 1916 edition of La Bos del Pueblo included a letter from a woman concerned about an Ashkenazi-Sephardi romance. The translated letter appears in Sephardi Lives, Item #119. Image courtesy of the Jewish Historical Press, Tel Aviv University.

SAS: “It is so very hard to choose! To me, the most moving voices in this book are inter-familial. I think of a 1917 letter, penned by a sister in Salonica to her brother in Manchester, that offers a first-hand account of the terrible fire that decimated that culturally rich Jewish city [Item #28, p.87]; or a letter written (partly in code) by a husband to his wife from the internment camp of Drancy, during the Second World War [Item #90, p.265]. The book includes a series of Ladino-language reflections, composed in 1778, on the advice a mother should offer her child [Item #7, p.34]; and a wonderful 1916 letter submitted to the editors of a Ladino journal in New York City by an immigrant Russian Jewish woman who sought to know with certainty whether the man with whom she has fallen in love could really be Jewish as he claimed, despite the fact that he looked and gestured ‘like an Italian’ [Item #119, p.347]. These are the sorts of voices that are more often than not elusive in existing documentary histories—but are among the very richest sources, regardless of whether one is a scholar, student, or general reader.”

HP: That leads me to my next question! What audiences do you think will be interested in this book? What do you hope people will gain from it?

JPC: “Our core audience is in the classroom. Both of us are committed to using primary sources in teaching so that history comes alive for students and they can see how people have expressed themselves historically. This is empowering for students, to be given the chance to read history for themselves without mediation and interpretation by others. We hope that the volume will also continue to prove useful to scholars, as it’s unlikely that any one person will have mastered the fifteen languages and many regions, perspectives, and time periods contained within.”

“But the volume is certainly not intended only for scholars and students. It’s also designed for anyone interested in Sephardic history and culture, as well as that of the Ottoman Empire, the Balkans, modern diasporas, and Jewish history writ large. A number of people have commented how readable they find it. The texts are very short, generally ranging from a paragraph to a few pages; readers can pick the book up and be drawn into the world of one particular piece and then put it back down again. Because each piece is independent, returning to a new entry at a later date doesn’t disrupt the flow of the book, and sources don’t have to be read in any particular order to make sense.”

SAS: “The book has so much within it—documents about Sephardic culture, of course, but also about Sephardi Jews’ interactions with Jews of other backgrounds, as well as the Muslims and Christians they lived alongside. Because it explores so many facets of life over a wide geographic range and broad chronological sweep, it is our hope that it will be of interest to students of history (of all ages and levels) eager for original sources about everyday life and ordinary women, men, children, and families—sources that make history come alive. If I had to identify one hope I have for the impact of the book, it is that readers will better appreciate the internal richness and diversity of Sephardic culture, which can’t be reduced to a single typology.”

HP: What aspect of Ladino Day in Seattle are you most eagerly anticipating?

SAS: “For me, a return to the University of Washington is a return home: I am excited to see colleagues and friends, and to observe the fantastic expansion of the Sephardic Studies Program.”

JPC: “I personally never imagined that this book would come alive in the mouths of native Ladino speakers—that they would be reading the texts out loud in their original Judeo-Spanish versions at a public event. What better way to give voice to these voices from the past?”

Links for Further Exploration

- RSVP for Ladino Day 2015

- Celebrate Ladino Day 2015 at the UW on Dec. 6th – Preview article by Ty Alhadeff

[…] Read more… […]