Advertisement for Goodman’s matsa. Forverts, April 12, 1935. (Source: National Library of Israel)

By Makena Mezistrano

In April 1935, Passover was in the air on New York’s Lower East Side. All you had to do was open your Jewish newspaper of choice to feel the holiday approaching: In addition to the usual advertisements for dentists and lawyers, suits and shoes, readers would find a bevy of ads for the season’s most essential item: matsa (or matzah/matzoh). Whether on the pages of Forverts (The Forward), the city’s largest Yiddish daily, or La Vara, the longest running Ladino newspaper in New York, Sepharadim and Ashkenazim alike were inundated with reminders to purchase the unleavened, cracker-like product that would be at the center of their Passover tables come April 18th.

While it appears that some specific brands and services advertised in Forverts and La Vara did not often overlap (a phenomenon worthy of further investigation on its own), matsa ads were an exception. This was a discrete item with limited suppliers, and all Jews who celebrated Passover needed it. The only way for the matsa distributors to reach all consumers — Ashkenazi and Sephardic alike — was on the pages of the city’s different Jewish language newspapers.

A new comparison

Matsa advertisements in the American Yiddish and Ladino presses offer a rare opportunity to place these two communities in dialogue with one another, instead of only positioning them as separate or in bitter conflict — two common assumptions about intra-Jewish relationships in twentieth century New York. Unlike the Yiddish ads, which were likely original compositions by the Eastern European Jewish-owned brands themselves, the Ladino ads in La Vara were often close adaptations. And while many elements were retained, from the messaging to the design, some ads were clearly reimagined to be more suitable for a Sephardic audience — perhaps an act of interpretation at the hands of the Ladino copywriter. (Though we cannot definitively know this writer’s identity, it may have been the paper’s editor, Albert Levy.)

What might the matsa ads tell us about the imagery, words, and phrases related to matsa and its industry that resonated most among Sepharadim and Ashkenazim on the Lower East Side? And, with a sensitivity toward translation as interpretation in mind, what might these advertisements reveal about interactions between Sepharadim and Ashkenazim in 1930s New York?

Advertising imagery: What does matsa look like?

Ladino advertisement for Meyer London’s matsa; the headline claims the factory is the “largest and most modern in the world” (la mas grande i la mas moderna faktoria de matsa en el mundo). La Vara, April 12, 1935. (ST01113, courtesy Richard Adatto)

All matsa advertised in the Yiddish and Ladino presses by this time was commercially made, a byproduct of the industrialization of many other American food products that increased dramatically during the early twentieth century. Machine-made matsa was square and fit neatly in a box made for easy shipment, and such depictions of matsa were ubiquitous in both La Vara and Forverts by 1935.

But square matsa did not always resonate with Jewish readers. Extensive histories have been written on the Jewish legal (halakhic) controversy stirred among Ashkenazim by the shift from handmade, round matsa to machine-made, square matsa — a debate that began in Eastern Europe in the 1850s and continued in the United States decades later, mainly with Manischewitz matsa.

For Ashkenazi Jews, round matsa was by definition “traditional.” Any other shape was not only a problematic departure from tradition, some rabbis argued, but even an emulation of non-Jewish practices — a category of behavior prohibited by Jewish law. Another concern, among several others, was whether the machine-made matsa was even kosher for Passover at all: without extensive human involvement, the matsa was susceptible to contamination with leaven (in other words, machines weren’t as trustworthy as people) thus rendering it inedible during the holiday.

Though rabbinic approbations were necessary to soothe concerns over the acceptability of the newfangled matsa, advertising also played a critical role in acquainting consumers with the new shape and its production process. Ads not only highlighted that sealing the matsa in a box kept it fresher for longer, but many — Yiddish and Ladino alike — underscored a brand’s high standard of kashrut (adherence to kosher dietary restrictions).

In the below Ladino ad for Goodman’s matsa, for instance, the copy claims that the product is “kasher for Passover for the most observant Jews” (kasher para pesah para los djudios los mas observadores). Its Yiddish counterpart is similar: “the country’s greatest rabbis confirm the strict kashrut standards” (di greste rabonim fun land bashtetigen di shtreynge kashrus).

Ladino ad for Goodman’s matsa. The bold line in the paragraph reads “the best square matsot, Goodman” (las matsot amijoridas kuadradas Goodman). La Vara, April 12, 1935. (ST01113, courtesy Richard Adatto)

A Yiddish advertisement for Goodman’s matsa. The slogan in between the bold words at center is “crisp, square” (krukhle, skvere). Forverts, April 15, 1935. (Source: National Library of Israel)

Despite the similar imagery and messaging for Goodman’s matsa in the two papers, we cannot assume that Ashkenazi concerns, and subsequent commercial tactics, transferred onto the Ladino context. Rabbinic literature indicates that in Izmir, matsa was square (even if not necessarily machine-made) as early as 1858; thus, Izmirli arrivals to the United States would have already been familiar with Goodman’s imagery in La Vara. In repurposing Yiddish ads in the Ladino paper, then, retaining the illustration of boxed matsa was perhaps of no consequence.

On the other hand, new arrivals from Salonica — like the editor of La Vara himself — likely would have been surprised by the square product. There, matsa was distributed by the synagogues in broken pieces so large that they had to be kept in chests in people’s homes — a memory reflected in oral history accounts, and even by my own grandmother. And while it does not appear that Salonican Jews wrestled with halakhic concerns over square matsa or its adherence to kashrut, rabbinic literature out of North African and from Syrian communities indicates a controversy parallel to the Ashkenazi one.

Did the producers of New York’s square matsot consider their Sephardic audience when crafting their ad campaigns? Given the lack of awareness that Ashkenazi Jews likely had about the customs of their Sepharadic neighbors, it’s highly unlikely. At least some Sepharadim would not have required reassurance that square, machine-made matsa was acceptable — thereby complicating the narrative about the matsa controversy in the United States and beyond.

Delivery trucks outside Streit’s matzo factory on Rivington Street in the Lower East Side, 1935. The factory officially closed in 2017. (Source: The Atlantic)

Adapting to La Vara’s mission: Who are the consumers?

We may now turn to Manischewitz — the aforementioned Cincinnati-based brand at the head of the matsa controversy and named for its Prussian-born founder, Behr Manischewitz. The brand’s investment in advertising, and its high quality product, eventually cornered the market. By the 1920s Manischewitz purportedly delivered matsa to 80% of Jews in the United States and Canada.

While some Yiddish and Ladino Manischewitz ads were visually quite similar, other elements were noticeably removed in the Ladino version — in this instance, the holiday tablescape in the ad’s background. While this revision may be a simple design choice, there is a more compelling explanation: that the imagery was intentionally deleted in order for the ad to better resonate with Sephardic readers.

Ladino ad for Manischewitz matsa. La Vara, April 12, 1935. (ST01113, courtesy Richard Adatto)

Yiddish advertisement for Manischewitz matsa. Forverts, April 1, 1935. (Source: National Library of Israel)

The tablescape depicted in the Yiddish version may be part of the aforementioned tactic to assuage religious consumers by depicting a “traditional” Ashkenazi home. Yet these tall candlesticks would have been unfamiliar to Sepharadim, as many only used wicks in oil for ritual lighting.

While both advertisements tout Manischewitz as “the best” matsa (mijor ke todas las otras in Ladino; di beste in Yiddish), there is another clear addition to the Ladino version. Although both La Vara and Forverts were directed at the working class, only the headline of the Ladino ad speaks directly to the proletariat: el puevlo la demanda — “the people demand it.” The term el puevlo resonated with the rhetoric of Ladino newspapers from Salonica to Izmir and beyond that sought to cater to the needs of the common people — a phrase absent from the Yiddish iteration.

Appealing to Sephardic tastes: What do consumers want?

Most matsa advertisements in La Vara and Forverts also featured matsa products, including matsa meal; special cake flour; and egg- and whole wheat varieties of matsa. One notable Ladino representation of a popular Ashkenazi Passover product occurs with matzo farfel — small pieces of matsa used in baked goods. Ladino ads from various matsa brands render this food item as matsa minuda — “small matsa” — instead of attempting to introduce a Yiddish phrase to Sephardic readers.

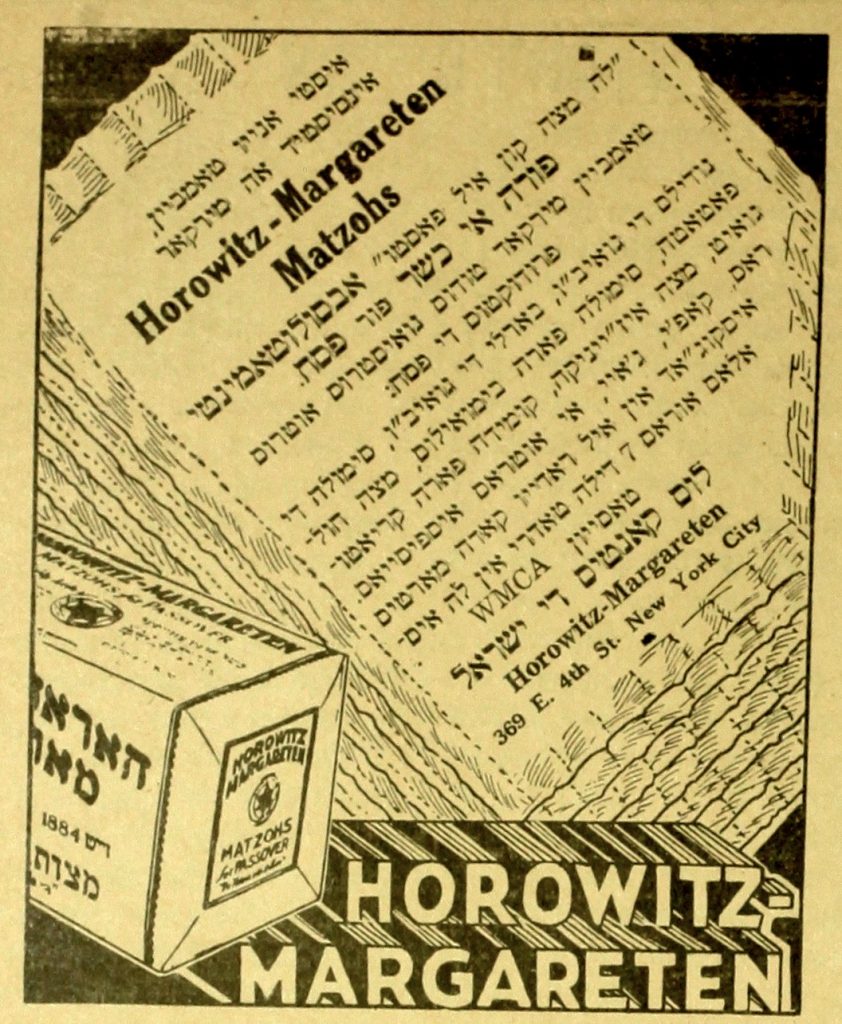

Ladino advertisement for Horowitz-Margareten matsa that includes products uniquely enjoyed by Sepharadim. La Vara, April 12, 1935. (ST01113, courtesy Richard Adatto)

A more dramatic rewriting of a Yiddish ad to accommodate Sephardic tastes occurred with Horowitz-Margareten, a matsa brand local to the Lower East Side. Beyond the usual products included in the Yiddish ads, the Ladino one includes simola para bimuelos (flour for bimuelos) and chai (a Turkish tea, and the Ladino word for tea in general). Most Yiddish ads across brands specify matsa meal for cake, which has been removed from this Ladino clip. The choice to highlight bimuelos (also spelled bumuelos, and multiple other ways), a fried donut-like treat commonly enjoyed around Passover time, is a clear adjustment for a Sephardic audience.

Rethinking the American Jewish food narrative

Until now, the narrative surrounding Jewish food production and Jewish consumer habits in the United States has been told from an exclusively Ashkenazi perspective. These matsa advertisements help us reconsider that story. As we have seen, Sepharadim were not only targeted by the same brands as Ashkenazim, but in some cases may have even been active interpreters of the advertising messages conveyed in the Yiddish press.

A reassessment of Jewish food history in the United States using matsa ads is particularly appropriate. Matsa is central to the Passover seder, the holiday meal during which we are compelled to ask questions — the same questions each year, even when we have already heard the answers. Every seder (or seyder) offers a new way to approach this dialogue. So too in our study of Jewish history: As we become aware of new sources, we can reconsider our assumptions, revisit our questions, and tell a new story.

Stay up-to-date with new digital content from the Sephardic Studies Program. Subscribe to our quarterly e-newsletter.

Mersi muncho (thank you) to Rabbi Ben Hassan (Sephardic Bikur Holim Congregation), Al Maimon, Hannah S. Pressman, and Shalom Sabar (Hebrew University of Jerusalem) for providing sources, insight, and assistance with the Yiddish for this piece.

Further reading

Benayau Cohen, “Machine Baked Matzah Comes to Galicia.” Ad Hena: Advanced Center for the Research of Galician and Bukovinian Rabbinic Culture (Hebrew, online, no date).

Jonathan D. Sarna, “How Matzah Became Square: Manischewitz and the Development of Machine-Made Matzah in the United States.” Sixth Annual Lecture of the Victor J. Selmanowitz Chair of Jewish HIstory at Touro College (2005).

Jeffrey Yoskowitz, “American Processed Kosher.” “Gastronomica,” vol. 12, no. 2. University of California Press (2012).

Makena, this was and is,,an excellent article. You went into the subject with a depth I never would have expected to see.

Hazaka Uvruha.

A fabulous article. Having been raised Sephardic, I love reading articles and books about our culture, but I’ve never seen such an in depth article about the advertisements of the same matzah to two different cultures. Also, the transliteration of the Latino ads made it quite easy to read them in Hebrew characters… always a challenge for me. WELL DONE!!!

Fascinating!

Do we have an idea of how wide the readership of the ladino newspaper was? How many copies were printed?

This was a really well-researched and interesting article. Thank you!