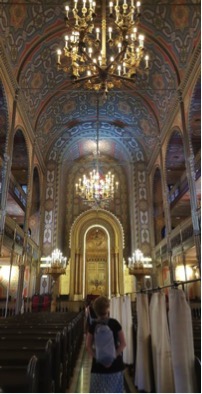

Ariel Vardy won a Jewish Studies Travel Grant to study Jewish identity in the Black Sea region. This synagogue is in Bucharest, Romania.

An Encounter with a Georgian Jew

Yotom Sakashvili, the manager of the Great Synagogue in the Republic of Georgia, is a happy-looking man with a kippah (skullcap) and a few missing teeth. We connect eyes as I walk up the synagogue steps. I walk through an open metal gate where a handful of men are shuffling around wearing white tallitot (prayer shawls). When I first entered the grounds, the men looked so purposeful in the backdrop of the large brick synagogue, but having drawn my attention to them, I see that they are quite aimless. Maybe just one or two among them might be a working citizen; with such a high unemployment rate, the synagogue is a sound place to spend the long hot day. And among them, just Yotom connected with me through eye contact and shook my hand as I approached. He waits expectantly for me to speak first.

“Is this a synagogue?”

“Yes,” he answers, staring into my eyes, still waiting.

“Can I go in?”

“Go in!” he says, with the quintessential Yiddish intonation that makes the question seem obvious. He lets me enter and then follows behind me, carefully tracing all my steps as I walk. Wooden benches line the place, and add a stained brown tone to the intricate palate of blues and whites tracing stars of David on the wall in an interlocked pattern. There is a religious raised platform (reminiscent of a tall lifeguard’s chair) and an altar at the end. Although beautiful, the architecture is an identical match of colors, style and materials to that of the churches in the surrounding Balkans. It seems to me that the church-maker decided to switch out the usual colors to match the Israeli flag (blue and white), and then did his normal work. Somehow, amid this brightly ornamented and catholic-like architecture, I did not quite feel Jewish in the familiar way.

“Yotom, I am doing a project on the Jewish experience, can you answer a few questions?” I ask. Looking weary, he walks out of the room and shows me a very small inscription about the Synagogue’s origin. The question seemed to sting him as he leaves the room quickly without a smile.

Conversations about Identity and Ethnicity

What I experienced in more places than one during my trip through Eastern Europe this summer was a survivor-like intensity to conversations and reflections about Judaism. Yotom represents a particularly strong example of the archetype I was starting to understand. , and upon seeing his fleeting friendliness, I started wondering about what lived culture and history he was talking through.

This synagogue in Tblisi, Georgia is an identical match of colors, style and materials to that of the churches in the area.

Yotom eventually passes me off to the Synagogue’s Rabbi. Rabbi Chaim spoke in a deep and charismatic Hebrew, totally lacking any foreign accent despite his citizenship and ethnic roots in Georgia. I have translated his remarks into English: “We have always been happy here, living in the Jewish sector with a school, butchers, and strong community.”

During the many lectures offered in my Study Abroad program, I had been studying the Georgian identity, and how integral the Georgian Church and the Georgian “Mountain Warrior” archetype was to this Balkan region. I asked the Rabbi, “How do you think the congregation identifies? As Jews? As Georgians? As something else?”

“We are all definitely Jews here. Sometimes, when we speak the same language, or eat the same food as our neighbors, we can say we are a ‘Georgian’ sub-sect, but we are first and foremost Jews.”

Ya’acov, an older, slower moving man who was one of the last the people to leave the synagogue, embodied these words. Attending the other synagogue of Tbilisi, only a few blocks down the street, he told me, “I go here because I am Jewish, I know I am Jewish in my heart!” He finishes a long speech about how he does not speak Hebrew or know prayers, but has memories of his parents owning dusty old prayer books in Hebrew. To him, a culturally secular man who grew up without much Jewish education but who now goes to synagogue weekly, “being Jewish” is a type of citizenship unrelated to where you are living. Strong enough such that that he attends synagogue services weekly despite not knowing what he is saying or engaging with the intellectual/philosophical questions that Judaism traditionally encourages.

Although reminiscent of the stance many a Jew would take, and similar to the summer camp experience of numerous secular American Jews, I think he meant the citizenship semi-literally. To him, and other Jews I spoke to in the Balkans, being Jewish was undersood literally as an ethnicity. Lectures I attended would list ethnic groups such as Azeri, Armenian, Osettian, and Jewish.

Locals I spoke with in Georgia treated ethnicity very differently than we do in the states. Your country of origin was not necessarily a sufficient answer to the question “What are you?” That is, they never asked “Where are you from?”; instead they asked variations of the ethnicity question for which your answer must be tied to an ethnic group that spoke a unique language. Interestingly then, nationality and religious background were not quite as meaningful as ethnicity, which encompassed Judaism for those that identified and those that didn’t.

Religion in the Post-USSR

This makes some sense in the context of history. The rhetoric coming from the Kremlin during the height of the USSR tried to induce a united USSR identity and reduce any national streams. For this reason, Armenia was not allowed to officially commemorate or recognize the Armenian Genocide, and Stalin never quite made it clear that he was Georgian because, as ruler of USSR, he was de facto Russian.

Which whittles down to my basic question: What does Jewish identity look like outside of the English-speaking west, and what is producing it? In America, the answer alludes to rich experiential learning opportunities like synagogue or summer camp. During the time of the USSR, all such religious experiences were strictly prohibited. These religious questions helped me see what it really was like day-to-day, community to community, to live in the USSR.

The outside of the synagogue in Bucharest, Romania.

Meanwhile, communities in Romania and Georgia were fleeting as more and more citizens moved to Israel. Chaim tells me of how the Jewish community shrank to about 1/3 its original size during the aliyot (waves of immigration) to Israel (mostly from 1948-1953).

The Jews I met all went to synagogue weekly, regardless of what they knew. The Jews I met wore their Judaism like a badge, instead of a small hidden piece of themselves. Now, post-USSR, not all made the time to take part in Hebrew and religious classes, or stay put in the Jewish quarter, which now seems like a distant claim to bring tourists to an average neighborhood. Nevertheless, they are compelled to stake themselves a place in the weekly (or daily, if you loitered) Jewish community synagogues. Although this makes sense in reference to the people’s past, it is not universal.

As the Rabbi and I finish our conversation, many of the congregants started to exit the building. Surrounded by a small flock, I realized how cool it was that we could converse in Hebrew as a middle language. The basic fact that Chaim knew Hebrew points to a strong community of congregants that live and breathe Judaism, such that even language education often kept the tightly wound connection to the tradition. What I was finding, was that while summer camp created a temporary ‘Jewish bubble’ as an educational experience, these Jews abroad found themselves in a real Jewish bubble, where the congregation, the language, and the way of life defined what ‘Jewish’ meant without having to intellectualize the concept of identity. They were living Jewish, in which it occupied the whole of them, instead of a segmented part.

In my summer travels at the fringe Eastern European communities, the Judaism felt as real as it felt foreign. And somehow, on my journey to question the Jewish experience, I ended up catching a fly on the wall view of the passing history, identity and community engagement of these unique communities.

Ariel Vardy won a Jewish Studies Travel Grant to visit the Black Sea region and research his family roots in Romania. He is a Junior in the UW Comparative History of Ideas Department studying intersections of History and Educational Psychology. His final thesis will be researching the link between learning and development and how various forms of development informs (or should inform) educational practice. Ariel’s research in the Balkans investigated the dynamics and politics of identities, which often play a powerful role in defining the quality of engagement within institutions. Ariel is from Sammamish, Washington, where his parents currently reside.

Georgia isn’t in the Balkans.