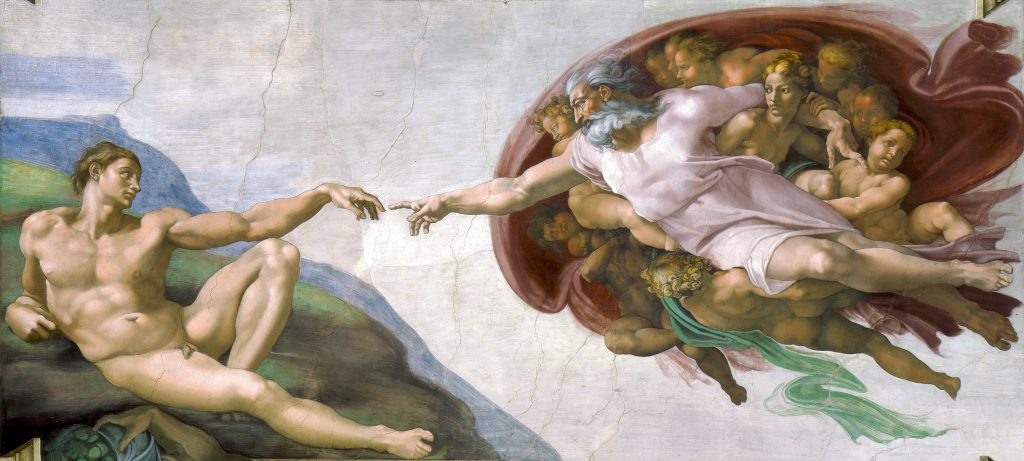

“The Creation of Adam.” Artist: Michelangelo, 1512.

By Benjamin Pollock

“The greatest thing you’ll ever learn,” crooned Nat King Cole in his 1948 hit “Nature Boy,” “is just to love and be loved in return.”

Baruch Spinoza clearly learned a great many things over the course of his short life, but Nature Boy’s “greatest thing” was apparently not one of them.

According to Spinoza, the intellectual love of God represents the very peak of human achievement and happiness. But when we turn to the middle of the fifth book of Spinoza’s Ethics, we find the following proposition: “He who loves God cannot strive that God should love him in return” (E5p19).

A handful of early 20th century Jewish thinkers – Hermann Cohen, Franz Rosenzweig, Joseph B. Soloveitchik – criticize Spinoza for thus rejecting the possibility that God might reciprocate the love human beings direct towards God.

Taking their lead, in part, from the German Idealist view (expressed especially clearly by J.G Fichte and GWF Hegel) that we only become full-blooded selves when we are recognized as selves by others, these Jewish thinkers advocated an alternative model of true love that highlighted the importance of reciprocity. Only reciprocal love – even in the case of loving God – entails the kind of relationship that respects the integral value of, and contributes to the healthy realization of, the personal selves of those in love.

The critiques of Spinoza offered by Cohen, Rosenzweig, and Soloveitchik drift towards the ad hominem, suggesting that Spinoza’s rejection of divine reciprocity in love amounts not merely to a philosophical failing on his part, but to a personal one. For that very reason – and because it is so easy to presume, intuitively, that the critique of Spinozist love is right – it is important to point out that in articulating his account of loving God in the way he does, Spinoza is heir to a long and venerable tradition.

The Tradition of Selfless Love

In several works, Maimonides presents a love of God which seeks nothing in return as the very ideal of divine service. Here he is, for example, in the “Laws of Repentance” from the Mishneh Torah:

One who serves [God] out of love occupies himself in the Torah and the commandments, and walks in the paths of wisdom, for nothing in the world: not because of fear of evil, and not in order to acquire favor. Rather, he does what is true because it is true, and ultimately, good will come of it. This is a very high level, and not every wise person attains it. It is the level of our Patriarch, Abraham, whom God described as “my lover,” for he served [God] out of nothing but love. (“Laws of Repentance,” Ch. 10)

In the view Maimonides presents here, service of God out of love just is serving God without any thought of reciprocation. It represents such a sublime relationship to God that few are able to attain it. As Maimonides himself points out, his account of serving God out of love, with no ulterior motive, is itself simply an elaboration of a very early proto-rabbinic teaching cited in the Ethics of our Fathers, Ch. 1: “Do not be like servants who serve their master in order to receive a reward, but rather be like servants who serve their master in order not to receive a reward.”

Closer to the time and place of Spinoza’s later critics, no less towering a German cultural figure than J.W. v. Goethe found in Spinoza’s account of unreciprocated divine love an expression of the highest ethical attitude towards the world, an attitude Goethe himself strove to realize. Goethe recalls in his autobiography:

This spirit who affected me so decisively and who was to have such a great influence on my entire way of thinking was Spinoza. … What attached me to him especially was his limitless unselfishness which shone forth from every sentence [in the Ethics]. That wondrous statement: ‘Whoever loves God rightly, must not demand that God love him in return,’ with all the premises upon which it rests, with all the consequences which arise out of it, filled my whole reflection. To be unselfish in everything, to be most unselfish in love and friendship was my highest desire, my maxim, my practice, so that that sassy later statement, ‘If I love you, what does that have to do with you?’ was spoken rightly out of my heart (Dichtung und Wahrheit, MA 16:667).

Goethe finds in Spinoza’s account of divine love a model of unconditional love. In his eyes, Spinoza presents an ideal of selflessness which the human being should cultivate in all her relationships. It is an attitude which makes it possible, moreover, for one’s joy in love to be independent of the feelings and the actions of the object of one’s love.

The Two Models of True Love

Sculpture of Cupid, Greek God of love, embracing his beloved Psyche. Artist: Antonio Canova, 1787.

Rather than declare the argument between Spinoza and his later critics decided before it even begins – for who wouldn’t want to be loved in return! – what I’d like to suggest is that our philosophers present us here with two different models of “true love,” two models of an ideal form of love which is not (or is not merely) erotic love.

There is, first of all, true love understood as unconditional, selfless devotion – to God, to a cause or ideal, and perhaps to another person – in which the relationship one enters into raises one up, and allows one to identify with something or someone (perceived as) greater, even if this involves the effacement of oneself as individual.

Then there is true love understood as reciprocal, as a relationship in which each member recognizes, respects, and is invested in her beloved other, in a way that is constitutive of each lover’s very personhood.

It very well may be that the tensions between these two models for thinking about true love go all the way back to Plato and Aristotle. But they are certainly well represented among modern Jewish thinkers, as well.

Love, Ourselves, and Our Relationship with God

Behind the debate is a basic question about the role of love in determining how I become who I am, a question about how who I aspire to be is wrapped up with whom or what, and how, I love. And such questioning becomes religiously, and not merely existentially, interesting when one considers God as party to our loving relationships.

What role might loving God be understood to play in the formation of human selfhood? Is God to be understood as a supreme being to whom I submit myself, or with whom I seek to identify in my life? Or can I actually be understood as depending on God to recognize or to engage me, in some way, as part of the process through which I become who I am? And finally – a matter for speculation – in what ways might even God be understood as needing the love and devotion of human beings?

Benjamin Pollock is the Sol Rosenbloom Chair of Jewish Philosophy and Associate Professor of Jewish Thought at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. His writings include Franz Rosenzweig and the Systematic Task of Philosophy (Cambridge, 2009), winner of the Salo Baron Prize and the Jordan Schnitzer Award, and Franz Rosenzweig’s Conversions: World Denial and World Redemption (Indiana University Press, 2014).

Benjamin Pollock is the Sol Rosenbloom Chair of Jewish Philosophy and Associate Professor of Jewish Thought at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. His writings include Franz Rosenzweig and the Systematic Task of Philosophy (Cambridge, 2009), winner of the Salo Baron Prize and the Jordan Schnitzer Award, and Franz Rosenzweig’s Conversions: World Denial and World Redemption (Indiana University Press, 2014).

For Further Exploration

- “Spinoza on the Divinity of Scripture” by Steven Nadler, February 2017

- “Should the Ban on Spinoza Be Lifted?” by Daniel B. Schwartz, February 2017

Leave A Comment