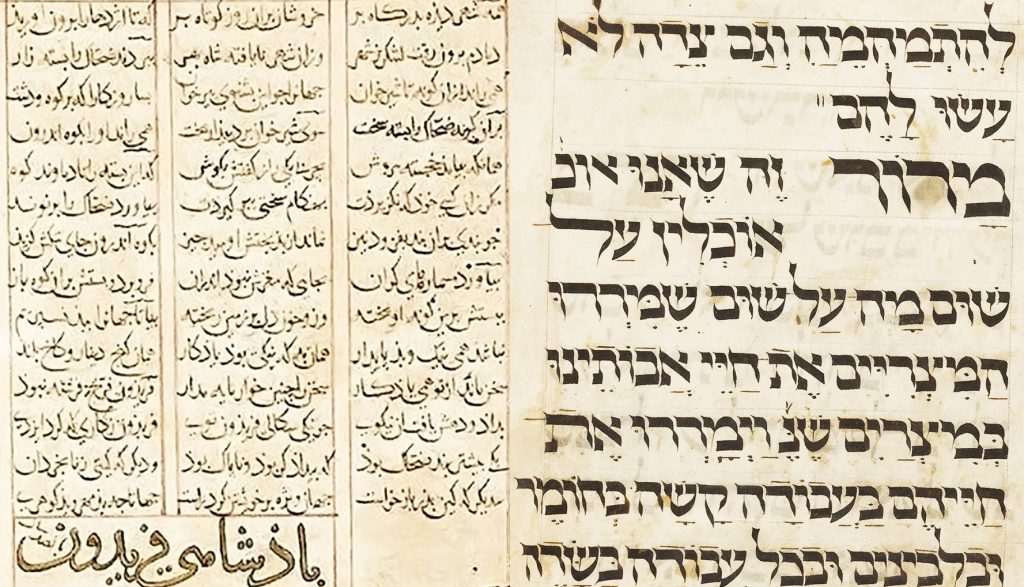

A page from the Persian epic The Shahnameh (“Book of Kings”, 1010 BCE) alongside a page from the Birds’ Head Haggadah (13th century)

By Sara Molaie

My first encounter with Judaism was in Winter 2013, when I enrolled in the Jewish Cultural History course taught by Professor Devin Naar. As an Iranian and a follower of the Baha’i faith, I found the Middle Eastern elements of Judaism very interesting. They were both familiar and at the same time new to me.

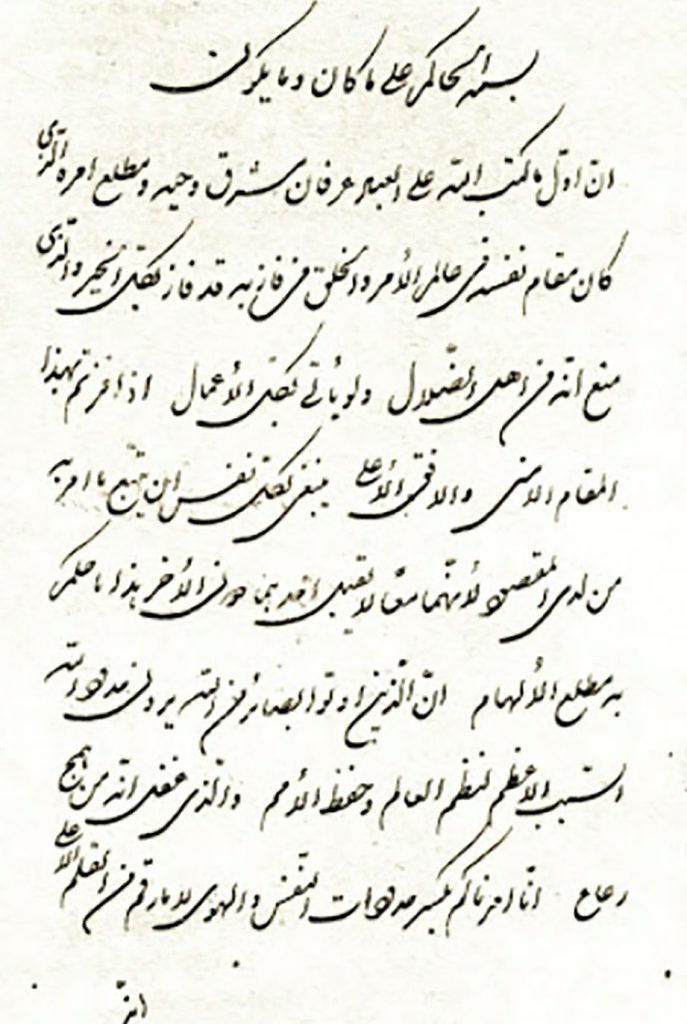

The first page of the Baha’i faith’s Kitab-i-Aqdas (“The Most Holy Book”), handwritten by Baha’i leader ‘Abdu’l-Baha

I was already familiar with the religion of Islam through my life experience in Iran, from my interactions with the larger society and from some of the required courses at school. I had also read some Islamic sources independently because of the references to Islam in the Baha’i writings, which come from 19th century Persia (today Iran), when the country’s religious context was Islam.

I found traditional Judaism to be similar in many ways to Islam: in the marriage laws, the prayer customs that divide men and women, and the dietary rules, as well as in similarities between the Semitic religious languages of Arabic and Hebrew. Judaism was new to me in some ways, also, with the unique history of the Temple, the racial aspect of Jewishness, and imagery like eternal light and the menorah.

As I continued to take Hebrew courses as a Jewish Studies minor, what was more surprising was my discovery that the Persian and Hebrew languages and their histories also had unexpected connections.

Linguistic and cultural connections

Last year I enrolled in the course Prayer and Poetry in the Judeo-Muslim Tradition, taught by Prof. Naomi Sokoloff and Prof. Samad Alavi, which covers primary sources in Persian and Hebrew. This allowed me to study Hebrew, a Semitic language, alongside Persian (Farsi), which is an Indo-European language, and to see the similarities in a new way.

A lot of poems in Persian were influenced by Islamic ideas, and presented concepts that were similar to those in the modern Hebrew poems: religious ideas of the End Time, for example, with fire and water as a punishment, and a final reward for the sinful and the sinless.

There were also linguistic overlaps between the languages. The words for religion, geometry, and sugar, for example, are all similar in Persian and Hebrew. Sugar is pronounced shekar in Farsi, while the Hebrew pronunciation is sukkar. Sometimes words with similar pronunciations are also conceptually related: the Hebrew word for orchard or grove is pronounced pardes, which has the same sound as the Persian word for “paradise.”

These connections were fascinating to me, because they demonstrate that there were exchanges between Hebrew and Persian cultures, and that they existed from ancient times.

A tale of two revival movements

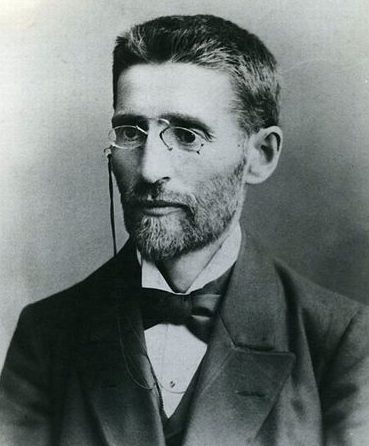

Photograph of Maneckji Limji Hataria (1813-1890), Zoroastrian activist and leader of the Persian language revival movement

I also learned that spoken Hebrew was revived in the 19th century. This was interesting for me, as well, because there was also a revival movement – although unsuccessful – in Persian in the 19th century. In fact, beyond the conceptual and linguistic commonalities between the two languages, there was a historical similarity in these two language revival movements. (Read Sara’s full post about these two movements.)

The movements to revive Persian and Hebrew both concerned returning to the original (ancient) land to practice ancient traditions, and speaking the ancient language. Persian Zoroastrians had started a mass migration to India to escape persecution following the Islamization of Iran in the 7th century CE. In the view of movement leader Maneckji Limji Hataria, restoring ancient or pre-Islamic Iran – starting with the Farsi language – would let these migrants return to their ancestral land and merge with the broader Iranian society.

Both Persian and Hebrew had the potential for renewal at the same period in history, though the movements’ goals and circumstances were different. Persian was a spoken language already, while Hebrew was not spoken as a modern language when its revival movement began. Maneckji’s approach was to remove all the alternative (non-Persian) elements from the language, while Hebrew movement leader Eliezer Ben Yehuda wisely realized that the language’s openness to modern words and elements would allow Hebrew to thrive.

Eliezer Ben Yehuda (1858-1922), Hebrew lexicographer and leader of the Hebrew revival movement

I have decided to write my thesis on the comparative study of the two revival movement leaders, Maneckji Limji Hataria for Persian and Eliezer Ben Yehuda in the case of Hebrew. While it is typically understood that many language and cultural revival movements occurred across Europe and other regions because of the influence of the Enlightenment and nationalism, I think these two movements need more scholarship to understand why one (Hebrew) succeeded and the other (Persian) did not.

As I am moving forward, I am exploring fascinating facts about the cultural exchanges between the Persian world and the Hebraic realm. For instance, I recently discovered that the administrative language of the first Persian dynasty, the Achaemenid Empire (550-330 BCE), was Aramaic, which is a Semitic sister language to Hebrew.

Exploring connections like these shows how, when we look carefully, unexpected relationships can emerge between languages and cultures that at first seem very different from one another.

In the case of Hebrew and Persian, these two languages and cultures are not as independent and isolated from each other as we might first assume.

Sara Molaie is pursuing her Master’s in Comparative Religion in the Jackson School. As a member of the minority Baha’i community in Iran where she grew up, Molaie has had to overcome many challenges. After she immigrated to the United States in 2009, she focused her post-secondary education on religious studies, in an effort to contribute to raising awareness of the possibilities for multicultural coexistence. With a focus on Judaism and Islam, she completed elementary biblical and modern Hebrew and intermediate Arabic in her undergraduate and graduate studies at the University of Washington. Working on her MA thesis, which is related to the revival of Hebrew as a spoken language, she is going to advance her Hebrew in the summer as an FLAS awardee.

Sara Molaie is pursuing her Master’s in Comparative Religion in the Jackson School. As a member of the minority Baha’i community in Iran where she grew up, Molaie has had to overcome many challenges. After she immigrated to the United States in 2009, she focused her post-secondary education on religious studies, in an effort to contribute to raising awareness of the possibilities for multicultural coexistence. With a focus on Judaism and Islam, she completed elementary biblical and modern Hebrew and intermediate Arabic in her undergraduate and graduate studies at the University of Washington. Working on her MA thesis, which is related to the revival of Hebrew as a spoken language, she is going to advance her Hebrew in the summer as an FLAS awardee.