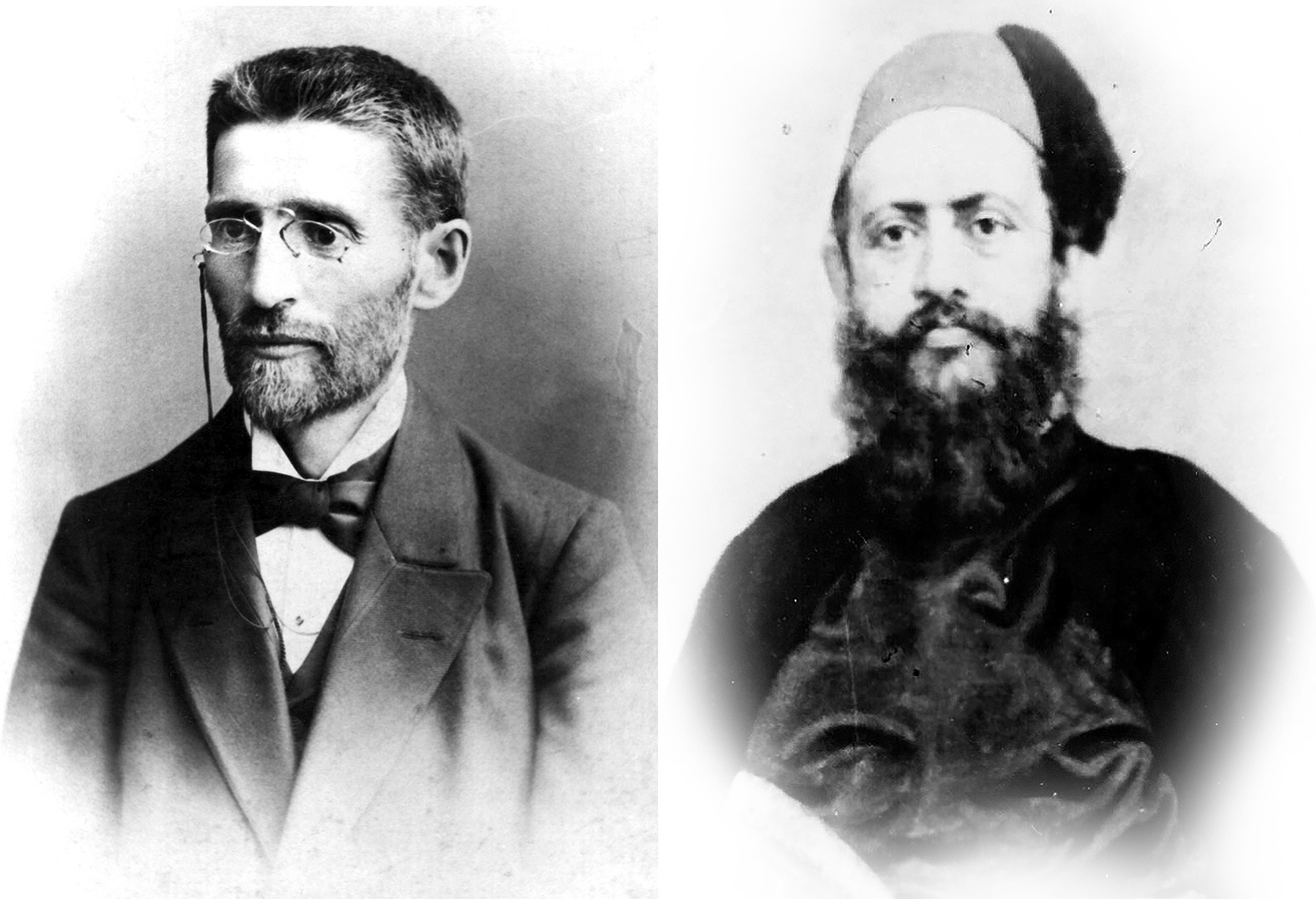

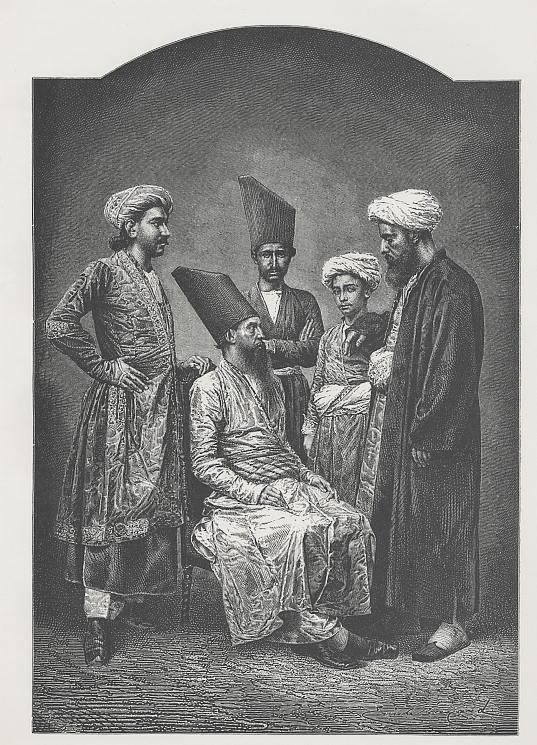

Eliezer Ben Yehuda (left) and Manekji Limji Hataria (right)

By Sara Molaie

In my graduate studies in Comparative Religion, I studied the language of Hebrew alongside Persian (Farsi) in courses like Prayer and Poetry in the Judeo-Muslim Tradition, taught by Professor Naomi Sokoloff and Professor Samad Alavi.

When I learned that Modern Hebrew was born out of a language revival movement in the 19th century, I was interested in the parallel to a similar 19th-century movement to revive a pre-Islamic form of Persian, which is my native language. I was inspired to write my master’s thesis on these two movements, and I focused on the two movement leaders, Eliezer Ben Yehuda, a Jewish writer, and Manekji Limji Hataria, a Zoroastrian activist, and the methods they used to try to revive these languages.

What were these methods, and what factors made one movement more successful than the other?

Reviving Hebrew

Born in Lithuania in 1858 to a Yiddish-speaking family, Eliezer Ben Yehuda had a traditional education that allowed him to become highly skilled in Aramaic and Hebrew at an early age. He later studied to become a rabbi, meeting teachers who were influenced by Enlightenment ideas.

As scholar Jack Fellman outlines, Ben Yehuda went through seven main stages in his efforts to revive Hebrew as a spoken language:

1. Speaking Hebrew in the family. After moving to Jerusalem in 1881, Ben Yehuda spoke Hebrew at home with his family. He ran into difficulties, because Hebrew lacked many basic words, and he would often have to resort to pointing at things to communicate. At this stage, only four other families in Jerusalem had adopted Hebrew as their spoken language.

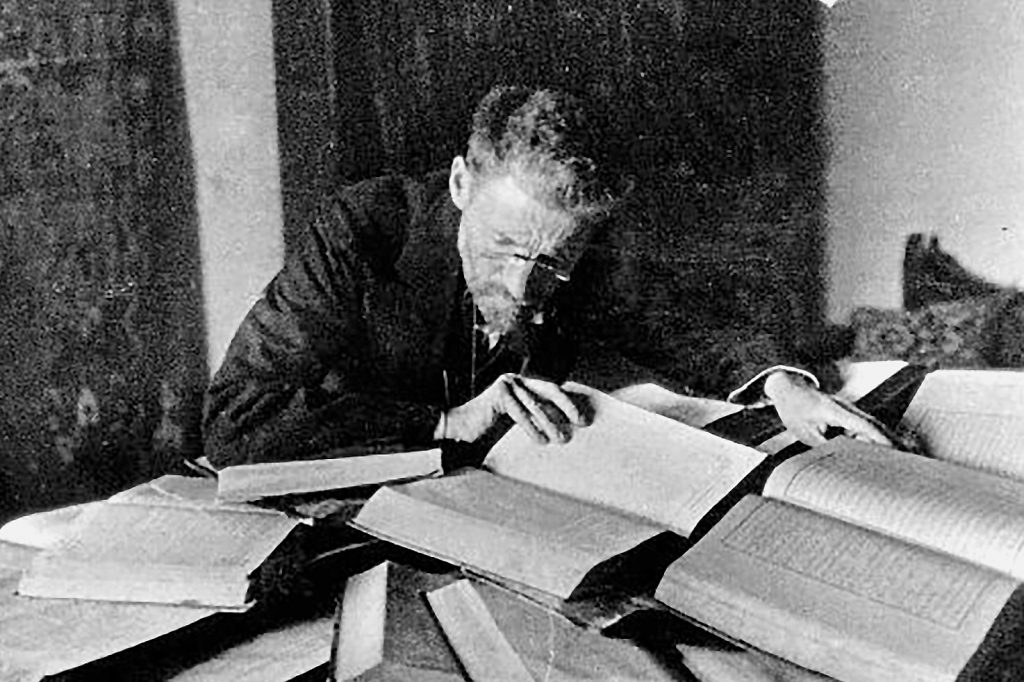

Eliezer Ben Yehuda pores over reference materials at his desk circa 1912. Photo by Shlomo Narinksy.

2. Calling on Jews in the diaspora as well as Jews in Palestine to speak Hebrew. Ben Yehuda edited several newspapers in Jerusalem, and through these papers began to disseminate the “revival” idea to Jews living nearby, as well as those back in Europe. In 1881, Ben Yehuda started editing the newspaper Ha-Havatzelet. The newspaper played two roles: it was a leading newspaper at a local level, and also served as a key system of communication with the Jewish diaspora. Networking with the broader Jewish community served Ben Yehuda’s revival movement well in the long term.

3. Establishing Hebrew-speaking societies. With the support of Yehiel Mikhal Pines, one of the main Jewish Enlightenment thinkers in Jerusalem, Ben Yehuda established a society called “The Revival of Israel.” Its aims included a) the revival of Hebrew as a spoken language, b) an agreement by members not to speak any language other than Hebrew, c) working to expand the language revival among the local population, and d) recruiting additional Hebrew teachers. This society was not entirely successful — it had to hold meetings secretly due to the opposition of Jewish traditionalists and Ottoman Turkish authorities — but it did influence future language revival societies, which followed the same principles.

4. Teaching Hebrew in schools. With the limited success of the previous steps, Ben Yehuda suggested using Hebrew as a spoken language between teachers and students in schools. In 1882, with support of Nissim Bechar, the principal of the Torah school of the Alliance Israelite Universelle in Jerusalem, Ben Yehuda became the school’s first Hebrew teacher, and would teach six to eight hours a day in Hebrew. He impressed other teachers, who continued using his immersion methods in teaching Hebrew. Ben Yehuda determined that, if children could speak Hebrew sufficiently at a certain age, they could not only inspire their parents to speak Hebrew but could also become fluent in the language as they grew up.

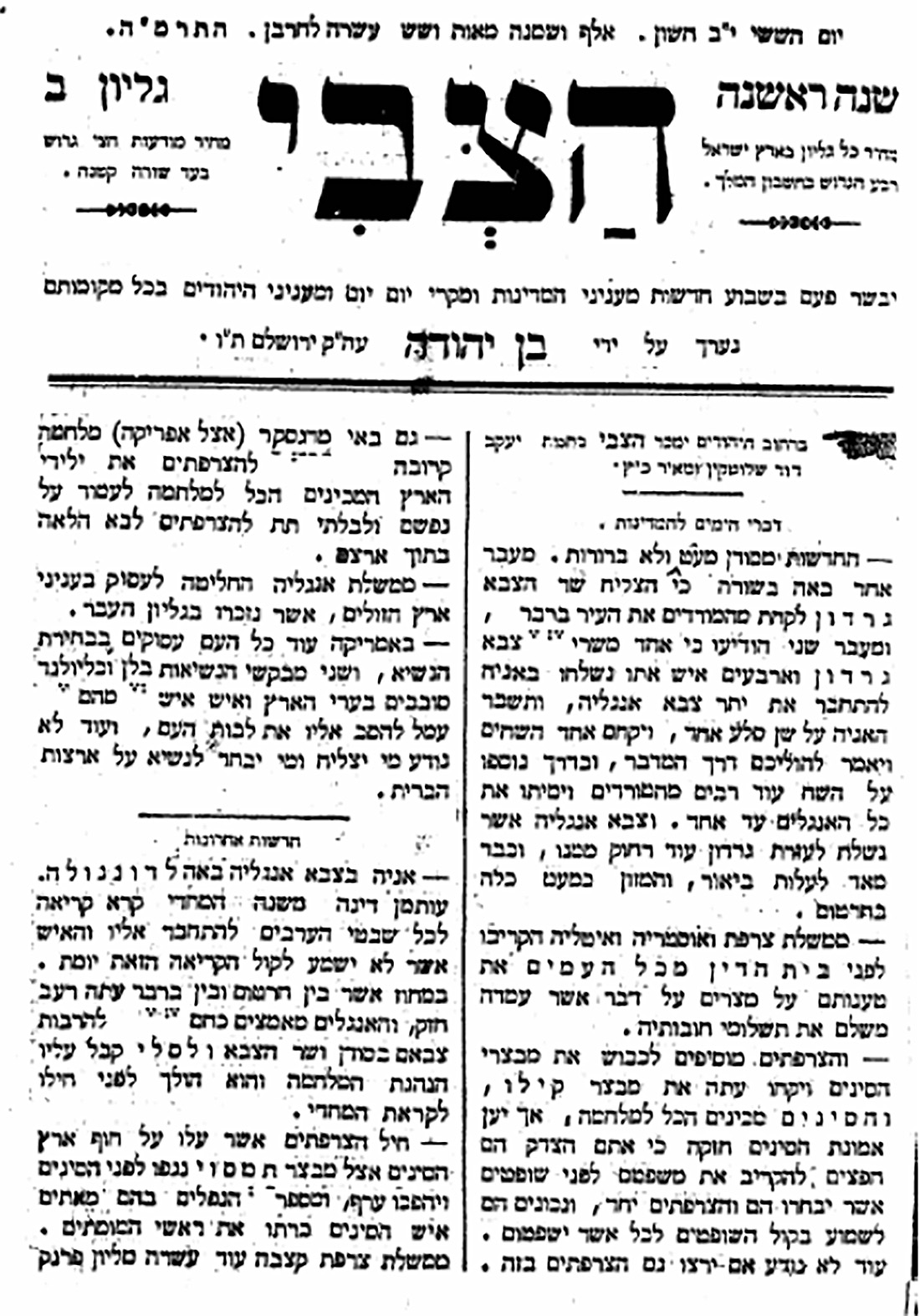

Front page of HaZvi newspaper, October 31, 1884. Editions online at the Historical Jewish Press website.

5. Creating Hebrew-language newspapers. One of the tactics to help promote the revival of Hebrew was the publication of Ben Yehuda’s personal newspaper, Ha-Zvi, written in a combination of Biblical Hebrew and post-Biblical Hebrew. Ben Yehuda began editing it in 1884, and devoted the content of the newspaper to human interest stories. It only had one problem: at the time, it had no readers in Palestine.

6. Creating the Dictionary of the Hebrew Language, Ancient and Modern. Ben Yehuda designed his dictionary as a manual for people who already had some background in Hebrew. His philological innovations and lexicographical work show that he attempted to unify Hebrew in all its periods and stages, treating it as a single continuously developing language. However, he did not plan the writing of the dictionary in an orderly way and his work was formatted more like an encyclopedia than a standard dictionary.

7. Establishing a Language Council. The dictionary work was not a task to be done singlehandedly, and Ben Yehuda did not want to be the sole decision-maker when it came to selecting and creating words. In one of his newspapers in 1889, he notes, “We are not able to say… ‘accept my judgment.’ Only a group of scholars together, who know the spirit of the language and all its …facets…, only they are able to form creations in this way.” In 1890, he founded a Literature Council that later became Va’ad Ha-Lashon (The Academy of the Hebrew Language). The Council’s main objectives were a) filling in the gaps in the language and b) creating of new words. The council’s efforts began to affect local society in the early 20th century.

Reviving Persian

Manekji Limji Hataria’s background goes back to the Zoroastrian migration from Iran to India in the Safavid period, between the 16th and the 18th centuries. Hataria was raised in a prominent Parsee (“Persian” / Zoroastrian) family in Surat, India, in which the language, history and culture of ancient Iran was highly appreciated. He received thorough traditional training, while also benefitting from the British reform of education in India. Hataria shared some common tactics with Ben Yehuda in his language revival mission:

1. Calling on the Zoroastrian diaspora in India to learn pre-Islamic Persian (but not as strongly as Ben Yehuda). During an information-gathering residency in Iran, Manekji sent reports on the conditions of Iranian Zoroastrians to the Parsee Bombay Amelioration Society. In an 1855 report, he encouraged the Society to fund the building of schools, temples and other centers for Zoroastrians in Iran. This project of amelioration was intended to help revive ancient Iranian culture, religion and civilization.

After returning to Bombay in 1863, Manekji again called on Parsees to fulfill the mission of reviving ancient Iran and working towards “the recovery of pre-Islamic literature.” Unfortunately, his correspondence with the diasporic community was not as frequent as Ben Yehuda’s newspaper publications. In India and in Iran, the Zoroastrian community also suffered from illiteracy, which made it difficult to implement Manekji’s recommendations.

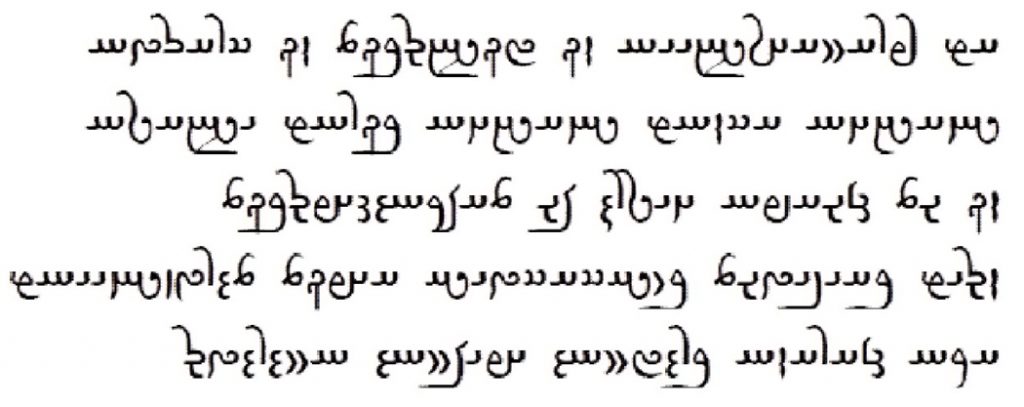

Writing in Avestan, the pre-Islamic script used to write Zoroastrian scriptures in around 400 CE. Via Omniglot.

2. Building schools. From 1858 to 1860, Manekji attempted to build schools for Zoroastrians in Tehran and other areas of Iran and attempted to give lessons on pre-Islamic Persian writing, though not many people were skilled enough to teach it. He hired Baha’i scholar Mirza Abu’l Fazl Golpayegani to be his secretary and teach students in Tehran, but eventually had to stop that project because of lack of resources.

3. Publishing books. Manekji wrote, edited, and encouraged the writing of many books on the revival of ancient Iranian culture and civilization. Some of these were published in Iran, but Manekji encountered difficulties in getting many of them printed: in some cases, the Iranian press would not agree to publish the books and he had to ask the Indian diaspora to publish his work instead.

4. Creating a dictionary. Manekji also supported Rezaqoli Khan Hedayat, the Persian literary historian, administrator, and poet, in writing a Persian-language dictionary for writers and speakers of ancient Persian.

5. Promoting literary associations. The first literary anjomans (associations) in Iran were intended to provide circles for the recitation and discussion of Persian poetry, the composition and editing of poetry and prose, and the publication of journals. These circles were led by members of the “literary return” movement, mainly by Mir Sayyed Ali Mostaq (1689-1757). In the late 19th century and the 20th century, especially after Iran’s Constitutional Revolution in the early 1900s, literary associations (anjomans) became widespread.

Goals, challenges and accomplishments

Ben Yehuda’s and Manekji’s language revival efforts had different goals as well as challenges. In the case of Manekji, the objective was to remove Arabic elements from the Persian language and to proliferate ancient Persian literature. In contrast, Ben Yehuda wished to create a vernacular version of Hebrew that would pave the way for Jewish nationalism, which required creating new words and importing new concepts into the language. Ben Yehuda not only had to persuade people to speak Hebrew for nonreligious purposes but also had to convince Jews to use words that had never existed before.

Wood engraving of “Parsees in Bombay,” 1878, by Emile Antoine Bayard (1837-1891).

For Manekji, although Persian was already a spoken language, struggling with the many deep-rooted Arabic elements in the language was a huge obstacle. Manekji could not speak Persian himself and only dealt with Persian through texts. He called on Parsees to fulfill the mission of reviving ancient Iran and “the recovery of pre-Islamic literature,” but he did not lay emphasis on the oral practice of the language. The revival objectives of Persian literary associations (anjomans) were broad, highlighting the writing of pre-Islamic Persian rather than the speaking of it.

Next to the abolishment of the jezya “poll tax” on non-Muslims in 1882, one of the most significant accomplishments of Manekji — and the most important goal of the Parsee Amelioration Society — was enabling Iranian Zoroastrians to access education. Manekji helped to improve Zoroastrians’ civil rights, built many schools in Tehran and other cities, and provided Zoroastrian boys and girls with Western-style education. Manekji’s appreciation of the pre-Islamic Persian language, ancient history, and cultural heritage of Iran influenced the teaching criteria in these schools. However, because of the lack of people with knowledge of the language, Manekji could not train his students in speaking or writing it.

In contrast, Ben Yehuda was able to convince school administrators in Jerusalem to teach in modern Hebrew, and he trained two other teachers to continue the work in his absence, continuing to spread the culture of speaking modern Hebrew. Teaching in modern Hebrew increased the number of speakers and, more significantly, let the language enter homes and streets of Palestine. As these children grew up, they started to become fluent in Hebrew and shape their own Hebrew-speaking families.

Ben Yehuda, unlike his conservative contemporaries, also realized that language can only thrive with dynamic usage. Adding words from a variety of non-Biblical sources — despite opposition from the rabbis and other members of the community in Jerusalem — was a crucial linguistic strategy that Ben Yehuda employed successfully, while Manekji insisted inflexibly on the purification of contemporary Arabi-Persian. Nineteenth-century Iran was strongly intertwined with Islam, so avoiding Arabic terms either in writing or speaking would have sounded very awkward. In other words, as a function of neo-Zoroastrianism, the revival of ancient Persian in 19th century Iran may have been overly ambitious.

Ultimately, Ben Yehuda was more fortunate than Manekji in his project because the awareness and education of the Jewish community he was working with was much more solid than that of Manekji’s Zoroastrian community. Iranian Zoroastrians had been deprived of basic education for many centuries because of persecution in Persia, and in spite of the Bobmay Amelioration Society’s efforts to increase access to education, the lack of schooling made it much more difficult for Manekji to accomplish his goals.

When the second Aliyah of Jewish migrants arrived in Palestine in the early 20th century, in contrast, the group was well-educated and financially stable. The adults were familiar with Ben Yehuda’s ideas and were interested in implementing them. Parents sent their children to Hebrew classes — some taught by Ben Yehuda himself — at school. This education system and the foundations it laid may have been Ben Yehuda’s most important contribution to the success of reviving Hebrew in the following decades.

Sara Molaie recently completed her master’s in Comparative Religion in the Jackson School of International Studies at the University of Washington. As a member of the minority Baha’i community in Iran where she grew up, Molaie has had to overcome many challenges. After she immigrated to the United States in 2009, she focused her post-secondary education on religious studies, in an effort to contribute to raising awareness of the possibilities for multicultural coexistence. With a focus on Judaism and Islam, she completed elementary biblical and modern Hebrew and intermediate Arabic in her undergraduate and graduate studies at the University of Washington.

Sara Molaie recently completed her master’s in Comparative Religion in the Jackson School of International Studies at the University of Washington. As a member of the minority Baha’i community in Iran where she grew up, Molaie has had to overcome many challenges. After she immigrated to the United States in 2009, she focused her post-secondary education on religious studies, in an effort to contribute to raising awareness of the possibilities for multicultural coexistence. With a focus on Judaism and Islam, she completed elementary biblical and modern Hebrew and intermediate Arabic in her undergraduate and graduate studies at the University of Washington.

Further Reading

- Discovering the unexpected connections between Persian and Hebrew by Sara Molaie (2018)

- Interview with Ilan Stavans: The beauty and history of the Hebrew language (2014)

Most interesting read. I am a Hebrew teacher in Johannesburg South Africa born in israel.

Can you please send me more information about your courses in Jewish and Hebrew studies.

Thank you

Hi Ariella, you can find a complete listing of our courses here: https://jewishstudies.washington.edu/all-courses/

And you can read more articles about Hebrew language and literature here: https://jewishstudies.washington.edu/category/hebrew-humanities/

[…] • ‘How to revive an ancient language, according to 19th-century Hebrew and Persian revivalists’ (University of Washington, 2018): https://jewishstudies.washington.edu/israel-hebrew/reviving-hebrew-persian-ancient-languages-eliezer… […]