A controversial mural, “People’s Justice,” covered up following a public outcry over antisemitic imagery, at the documenta fifteen art festival in Kassel, Germany, 2022. Photo by C.Suthorn, licensed under CC-by-SA 4.0

By Martin H. Schwartz

When Germans talk in public about antisemitism, what are they actually taking about? Sometimes it’s about immigration, sometimes it’s about Islam, and quite frequently it’s about critiquing the German establishment as such. But counterintuitively, my research suggests that, most often, what they’re not talking about is the experience of actual Jews.

German antisemitism discourse and antisemitism itself collided, spectacularly, in documenta fifteen, the 2022 edition of the world’s largest noncommercial exhibition of contemporary art. (Documenta is presented every five years in Kassel, Germany.) Antisemitism scandals — about works on display, curation, and exhibition organization — clouded the 2022 show from before its opening.

The context of the art world, which thrives on ambivalent meaning and emotion, made the disputes all the stickier. When concerns about antisemitism arose, the artistic directors — the Indonesian collective Ruangrupa — dismissed them as at best a German oddity.

In response, under public and administrative pressure, the governing body of the exhibition, representing the City of Kassel and the State of Hesse, convened a “scientific” (wissenschaftlich) committee to assess antisemitic content in the exhibition and the ways in which the organization and the curators dealt with it. Yet in doing so, they may have reproduced binary, hierarchical habits of thought that themselves underlie antisemitism, racism, and other forms of hate.

The curation of documenta fifteen and allegations of antisemitism

Ruangrupa, the Indonesian art collective directing the exhibition, formulated the concept of lumbung — an Indonesian term for a collective rice barn — as a way to ground documenta fifteen in a spirit of mutuality and sharing. Rather than act as curators in the traditional sense, Ruangrupa engaged other collectives both to create work for the exhibition and to engage yet other collectives in turn. As a result, there was no formal curatorial control over the artistic projects themselves.

In advance of the exhibition’s premiere, a fringe advocacy group issued a press release accusing the exhibition organizers of antisemitism. Their chief complaint was the inclusion of the West Bank Palestinian collective The Question of Funding, whose members, they asserted, support the BDS movement, a movement to “boycott, divest [from], and sanction” the State of Israel in order to influence its policy. In the days following, it became clear that no Jews were exhibiting in the exhibition. The public sphere took notice. Despite misgivings, which he expressed in his speech, the German President, Frank-Walter Steinmeier, attended the opening.

“People’s Justice” mural and lawn display at documenta fifteen, prior to the mural’s covering and eventual dismantling. Photo by Birte Fritsch

Afterwards, however, inarguably antisemitic imagery was found in a large work of protest art, which was presented in the most prominent square in Kassel: “People’s Justice,” by the Indonesian collective Taring Padi. This work includes, among representations of the powers of global oppression, an image of an Orthodox Jew with payot (sidelocks), a cigar, fangs, and the SS “thunderbolts” on his bowler hat. This depiction draws directly on traditions of representing Jews as vampiric, sensual, and aligned with imperialism and global finance, as well as benefiting from or even orchestrating the Holocaust. Opinions differ as to whether a second image of a Jew in the mural — depicting an Israeli soldier as a pig — also expresses antisemitic intent.

As the public took in more of the sprawling show, charges of antisemitism attached to further works. These included historical print materials in an archival exhibit from the collective Archives des luttes des femmes en Algérie. A leaflet on display depicted a short, ugly, hook-nosed Jewish caricature representing an Israeli soldier being kicked between the legs by a tall, strong woman fighter. Controversy also implicated films “on the Palestinian struggle” from the 1970s and 1980s, originally collected by a Japanese “Palestine solidarity group” and screened as Tokyo Reels.

The response to concerns around antisemitism

The documenta fifteen visitor’s center in Kassel, Germany. Photo by Baummapper

Media headlines used strong language to describe the exhibition, including calling it “Antisemita-15” and the “Kassel Horror Show.” Documenta leadership announced a series of public discussions, “We need to talk!,” to speak to “the fundamental right of artistic freedom in the face of antisemitism, racism and Islamophobia.” However, the established Jewish community was not included in these plans. Josef Schuster, the President of the Central Council of Jews in Germany, objected that the Council had been rebuffed by documenta organizers despite repeated requests to participate. For many, excluding the main body representing German Jews from a conversation about antisemitism in Germany was a bridge too far. The programs were called off.

Documenta’s general director, Sabine Schormann, offered the director of the Anne Frank Center in Germany, the Israeli Jewish scholar Meron Mendel, a position as external advisor to lead a collaborative panel to address antisemitic works in the exhibition. But after the announcement of Mendel’s involvement, no further action was taken, and Mendel felt the leaders were “buying time.” He then withdrew.

The artist Hito Steyerl, the documenta presenting artist best known to the international art world, very publicly removed her works from the show, decrying “antisemitic content” and “the repeated refusal to facilitate a sustained and structurally anchored inclusive debate.” General Director Schormann was forced to resign.

Ruangrupa remained defiant. Ruangrupa members Reza Afisina and Farid Rakun gave an interview in which Afisina claimed that “[o]nly through the debate did we learn what a sensitive subject antisemitism is in Germany.” When an expert committee on antisemitism was ultimately convened, Ruangrupa “collectively and categorically” refused to cooperate with it. They circulated their own document in response, characterizing the group of experts as a “censorship committee” and decrying harassment experienced by pro-Palestinian, Black and Muslim artists during the exhibition.

In an interview, Ruangrupa member Farid Rakun said that the “red lines” precluding cooperation with the committee included “calling the committee wissenschaftlich [a term that means both ‘scientific’ or ‘academic’ in German]. That comes from colonial history.”

The origins of modern antisemitism: A hatred of ambivalence

What is missing from Ruangrupa’s analysis was any concern for — or solidarity with—the experience of German Jews. Jews in Germany might justifiably have found it troubling that the country in which they live, the legal successor state to the Nazi dictatorship, had funded and platformed, at least in one case, the same sort of antisemitic imagery that preceded the Shoah. Moreover, if Ruangrupa were thinking of groups who have been made to suffer on pseudo-wissenschaftlich grounds, they might have considered the example of the Jews of Europe.

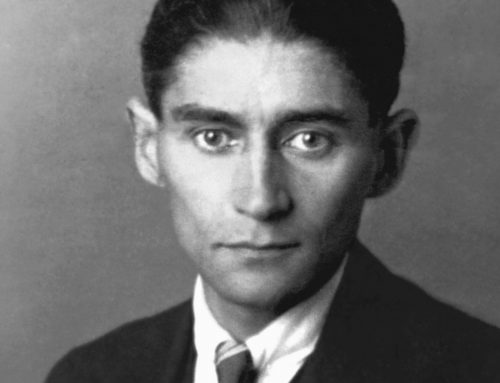

Sociologist Zygmunt Bauman, theorist of modern antisemitism, in 2008. Via the Open University of Catalonia.

But what of the collective’s objection to using wissenschaftlich methods to investigate antisemitism in the exhibition? For many scholars, the dualistic quest for true/false, good/bad answers to complex social questions has epitomized the hatred of Jews since the Classical Era, starting in ancient times. Polish sociologist Zygmunt Bauman argued that, over many centuries, Christian Europe cast Jews — neither pagan nor Christian — as “ambivalence incarnate.” Later, modern societies, with their mania for order, found in the Jew, who would not neatly fit into any conceptual category, a ready-made enemy.

Modern antisemitism, a racialized way of thinking about Jews ascendant from the late 19th century, continued to depict Jews as uniting incommensurable opposites. Nazi ideology is rich with examples. The Jew was, for instance, the hidden force behind both Russian anti-capitalist Bolshevism and international finance capitalism. Moreover, Jews supposedly had preternatural linguistic abilities but never spoke European languages like true natives. And Jewish men posed a dire sexual threat to Christian women while also representing effeminacy and dangerous queer sexualities.

As Saul Friedländer writes, to Nazis “the Jew was both a superhuman force driving the peoples of the world to perdition and a subhuman cause of infection, disintegration, and death.” The modern hatred of Jews was, in other words, inseparable from the hatred of ambivalence.

Continuing controversies around antisemitism

Faced with ambivalence, documenta’s leadership shut down dialogue and rushed to resolve uncertainties through a committee investigation and report. In this sense, one could view the top-down imposition of “science” as continuing the same fundamentally binary, with-us-or-against-us patterns that in fact facilitated both colonial rule and modern phobias, especially antisemitism.

Despite the scandals — or because of them — documenta 15 welcomed 738,000 visitors and involved some 1,500 artists. But the story doesn’t end in Kassel. The fault lines around antisemitism that the exhibition exposed — between camps identifying with postcolonial and culturally conservative interests — have reemerged with a vengeance since October 7, 2023, with cultural funding bodies in Germany attempting to codify many forms of critique of Israel as antisemitism. And in these debates, as in 2022, the experience of Jews in Germany is often instrumentalized and invoked, but seldom seems to be the point.

Martin H. Schwartz is a student and instructor at the University of Washington, where he is pursuing a Ph.D. in German studies and a certificate in cinema and media studies. After receiving his M.A. from the University of Chicago, he served in numerous roles in cultural curation and management, including as program curator at the Goethe-Institut’s Goethe Seattle Pop Up and as a film programmer at Seattle International Film Festival. Martin is a published playwright and an alumnus of the Anti-Defamation League’s Glass Leadership Institute. He currently holds a Hanauer Fellowship for Excellence in Western Civilization. He is a 2024-2025 Mickey & Leo Sreebny Fellow in Jewish Studies.

Martin H. Schwartz is a student and instructor at the University of Washington, where he is pursuing a Ph.D. in German studies and a certificate in cinema and media studies. After receiving his M.A. from the University of Chicago, he served in numerous roles in cultural curation and management, including as program curator at the Goethe-Institut’s Goethe Seattle Pop Up and as a film programmer at Seattle International Film Festival. Martin is a published playwright and an alumnus of the Anti-Defamation League’s Glass Leadership Institute. He currently holds a Hanauer Fellowship for Excellence in Western Civilization. He is a 2024-2025 Mickey & Leo Sreebny Fellow in Jewish Studies.

![Muestros Artistas [Our Artists]: Bringing Sephardic Art and Community Together at the UW](https://jewishstudies.washington.edu/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/UWJS_Muestros-Artistas-cropped-500x383.jpg)

The correct term is ambiguity, not ambivalence. Ambivalence means that someone has conflicting feelings about something. Ambiguity means that the thing itself may be interpreted in more than one way. It’s the difference between feelings about Jews, and Jews themselves and how they are viewed. As today’s AI will tell you, “The primary difference between ambiguous and ambivalent is that ambiguous refers to something that is unclear or has multiple possible meanings, while ambivalent refers to having mixed feelings or conflicting emotions.”

I appreciate your comment! While etymologically you are certainly right to point out that distinction, meaning and emotion are quite intertwined, as are, accordingly, ambiguity and ambivalence. Bauman referred to the latter in his writings about Jews, modernity, and proteophobia, and I use the term in that sense. AI may not be aware of this specific usage, but it’s certainly a tension worth teasing out.