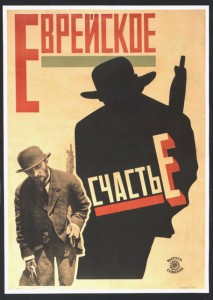

Film poster for the Soviet film “Jewish Luck” (1925)

Images of bombastic “sword and sandal” dramas or naturalistic shots of war-themed movies come to mind when the words cinema and history are combined in a single sentence. The film industry eagerly adopts historical events and refurbishes them for viewers, transforming them from the verbal domain of books into the visual domain that is the silver screen. Having a background in history, I was cautious about the cinematic representation of events as a legitimate field of study. Thanks to engaging lectures from UW professors, such as Galya Diment and Barbara Henry of the Slavic Languages and Literatures Department, I have realized the potential that film research carries. Motion pictures serve as valuable evidence of the social and political climate of the eras in which they were produced. Due to its costly nature, cinema is among the most vulnerable arts: in democratic societies film production depends on commercial success; in closed societies cinema is a product of State resources and therefore always under the watchful eye of the government.

During most of its existence the Communist Party exercised tight control over Soviet cinema, demanding that films conform to and serve its ideology. Concerning the primary role of movies in propaganda, Vladimir Lenin said, “of all the arts, for us the cinema is the most important.” These words were taken with the utmost seriousness by the Bolsheviks. The importance of cinema was proved by the mission it inherited from literature: not just to entertain, but also to enlighten people. The cinema adopted and fused the roles and methods of theater, literature, opera, ballet, and the visual arts in a way that was accessible to the general public. The Soviet film industry was closely and personally monitored by individuals at the highest level of authority, and it quickly responded to correspond with the Party’s shifting ideological demands.

Early 20th-century Russia was home to one of the world’s largest Jewish communities. Despite the First World War, Civil War, pogroms, and emigration, Soviet Russia still had a significant number of Jewish citizens, most of whom spoke Yiddish and lived in the former Pale of Settlement. The new medium of cinema was accessible to illiterate and non-Russian speaking populations. As a result, the Bolsheviks chose film as the model vessel to appeal to minorities. One of the earliest surviving Soviet films, Comrade Abram (Tovarishch Abram, 1919), promoted Bolshevism to Russian Jews by showing the atrocities committed under the tsarist regime, emphasizing that only the new Soviet state would protect vulnerable minorities. The Soviet state employed cinema as an outreach device to both the Russian population and ethnic minorities, and “Jewish sections” (Yevsektsii) were established to work with Jews to promote Bolshevism among the mostly Yiddish-speaking Jews of the former Pale of Settlement.

During its first thirty years, Soviet cinema produced several dozen films featuring Jewish characters, from early agitation newsreels to widely recognized works of art that were exported to the US and Europe. The characters and characterizations of Jews in Soviet films underwent transformations that reflected official policy toward them; Jews went from being depicted as poor shtetl Jews oppressed by the tsarist government to roles as equal members in and creators of Soviet society, ready to abandon their ethnic “peculiarities” by acculturating and integrating with their “older brothers,” the Russian nation. The social and cultural environment of the 1920s fused ideas of internationalism and the equality of nations within the Communist state, where class identity would prevail over ethnic and religious ones.

Poster for “Jewish Luck,” a silent film produced in the USSR in 1925.

Until the early 1930s, showcasing minority ethnic cultures was acceptable as a sign of Communist internationalism. Together with official condemnation of pogroms and discrimination, state-sponsored Yiddish culture and films strove to create enlightened images of the new Soviet state, where emancipated minorities like Jews had equal rights and became part of a multi-ethnic nation of workers and peasants. After 1928, however, as Soviet leaders realized the failure of their hopes for world revolution, and Stalin started promoting “Socialism in One Country,” Soviet cinema saw a retreat from cosmopolitan internationalism and a restoration of “imperial” values glorifying historical events and popular Russian leaders (such as Alexander Nevsky and Ivan the Terrible). Mirroring the ethnic Russian chauvinism of many films that looked to Russian history for contemporary Soviet models of nationhood, Jewish characters were reduced to deracinated and secondary roles. Jews almost completely disappeared from Soviet cinema during the Stalin-sponsored anti-Jewish campaign of the late 1940s-1950s, which was followed by a near-total retreat from Jewish themes (including that of the Holocaust) in the cinema of succeeding decades. Carefully censored and state-controlled, Soviet cinema is a visual document of the transformation of attitudes towards Jews in the Soviet Union.

In twenty years, Soviet cinema went from producing a significant number of Yiddish and Russian language films, aimed at both Jewish and non-Jewish audiences, to an almost complete absence of Jewish themes after the Second World War, including concealment of the Holocaust. Popular Jewish actors and directors were silenced and prosecuted. The Soviet state made a rapid turn from the ideals of internationalism and relative ethnic tolerance to the revival of Russian nationalism fused with Communist ideology. My project is a comparative overview of Jewish characters in Soviet films and visual culture of the 1920s-1940s that reflects changes in Soviet attitudes towards nationality policy in general and the “Jewish question” in particular.

This research is part of a larger project on the co-optation of imperial Russian historical themes and characters, particularly in the films of Sergei Eisenstein. If Soviet Jews had been the face of a cosmopolitan, internationalist Communism in the most popular of Soviet arts, where did Stalinism leave them?

![Muestros Artistas [Our Artists]: Bringing Sephardic Art and Community Together at the UW](https://jewishstudies.washington.edu/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/UWJS_Muestros-Artistas-cropped-500x383.jpg)