The entrance to the Moroccan Jewish Museum in Casablanca. Photo by Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin.

By Pablo Jairo Tutillo Maldonado

During a visit to Spain in 1989, His Majesty King Hassan II of Morocco met with the leaders of the Spanish Jewish and Spanish Muslim communities that originated in Morocco. In this meeting, the King delivered a powerful statement:

“I do not consider you Jews of Moroccan descent because Moroccan nationality is never lost. We consider you and all your brothers who live from Israel to Canada, in Venezuela, France, England, America, Latin America, and elsewhere, as Moroccan subjects who enjoy all the rights that the Moroccan Constitution grants you… Your rights are guaranteed by the Constitution because there are two events in the reign of my father Mohammed V and mine… Mohammed V made you Citizens. In my Constitution, I made you full Moroccans.”

The speech, in which King Hassan II invoked the national identity of Moroccan Jews in the diaspora, was made in Spain after almost the entire population of Jewish nationals had migrated out of, or were forced to flee, Morocco between the 1950s and the 1970s, due to spreading Arab nationalism and opposition to the State of Israel within Moroccan society.

In the late 1990s, the Foundation of Jewish Moroccan Cultural Heritage (FJMCH), a Jewish community organization, pushed to establish the Museum of Moroccan Judaism in Casablanca, Morocco, in order to raise awareness of Jewish identity in Moroccan national public discourse.

Today, despite the absence of Jews in Morocco — with only approximately 2,000 living primarily in the city of Casablanca — and some lingering anti-Semitism throughout the country, the Museum of Moroccan Judaism and other initiatives are attempting to rehabilitate the memory of the Jews of Morocco as indigenous Moroccan nationals and equal subjects of the Kingdom.

The modern history of Jews in Morocco

Moroccan Jews from Fez, circa 1900. From the 1901-1906 Jewish Encyclopedia. Via Wikimedia Commons.

The Jewish Virtual Library estimates the Moroccan Jewish population was at a height of 265,000 in 1948, when the State of Israel was established. Only approximately 60,000 Moroccan Jews immigrated to Israel after its founding, with the vast majority staying in the next decade to come.

However, the independence of Morocco from France in 1956 brought clashing ideas of national identity to Moroccan society that obligated non-Muslims, particularly Moroccan Jews, to justify their Moroccanness. In a time when advocates of Pan-Arabism — the ideology of unifying all the Arabic-speaking countries in one nationalist union — had begun to instigate anti-Jewish sentiments across the region, Moroccan Jewish members of government took to newspapers such as La Voix des Communautes, a Jewish newspaper for public servants, to write in their defense.

Abraham Serfaty, a member of the Moroccan Ministry of Industry, noted in the Maroc-Presse: “I am an Arab-Jew and I am Jewish because I am an Arab Jew.” Moroccan Jews sometimes exclusively identified as Moroccan, and used writing to emplace themselves within the public discourse. However, the demise of these newspapers and the disintegration of mixed political parties brought an end to the right of Moroccan Jews to call out the anti-Semitic sentiments in the country.

Approximately 200,000 Moroccan Jews still remained in the Kingdom following Morocco’s independence in 1956. However, Morocco’s entrance into the Arab League in 1958 led to more pressure from Pan-Arabists like Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nassar to define Moroccan national identity as Arab and Muslim. The result of this ideology on Moroccan society was the mass migration of Jews from Morocco, leaving only 50,000 in 1968, 18,000 by 1978, 4,000 by 2011, and 2,150 by 2018.

A little history on the Museum of Moroccan Judaism

The Museum of Moroccan Judaism in Casablanca, the only Jewish museum in the Arab world, was founded in 1997. The old villa where it is located, far from the center of the city, was originally established in 1948 as a home for Jewish orphans, constructed in memory of Murdoch Bengio by wife Celia Bengio.

Courtyard just beyond the villa’s main entrance. The museum wall reads “Dar al-atfaal Murdoch Bengio” (Arabic) and “Home enfants Murdoch Bengio” (France), which translates as “Murdoch Bengio children’s home”

In the late 1970s, the orphanage became a yeshiva, an Orthodox Jewish seminary or religious school, for approximately ten years. In 1995, Simon Levy, Jacques Toledano, Boris Toledano, and Serge Berdugo, founding members of the Foundation of Jewish Moroccan Cultural Heritage (FJMCH) not only helped to turn this site into a Museum of Moroccan Judaism, but also began restoring and protecting the vanishing structures and culture of Moroccan Jewish communities around the Kingdom of Morocco.

Today, Zhor Rahihil, a Moroccan Muslim woman who studied the anthropology of Muslim-Jewish relations in Morocco, serves as museum’s curator. Although most of the funding for the museum comes from multiple private sources, the curator position is funded by the Moroccan Ministry of Culture.

Reviving national identity

In “Framing of Jewish Identity in the Museum of Moroccan Judaism in Casablanca,” Sophie Wagenhofer writes that museums have become “places of negotiation — a process in which the curator as well as the audience are involved. Different perceptions and images of identity, society, or power are presented, challenged, questioned, accepted, or rejected in this space.”

Author Pablo Jairo Tutillo Maldonado alongside museum curator Zhor Rahihil

The Museum of Moroccan Judaism has provided a space that is not steered by the nationalist attempt to expel the Jewish minority from Morocco’s national history but is rather working to re-emplace it in its memory, building a contemporary narrative of a pluralistic, multi-ethnic, and multi-religious society in Morocco, indicating that Jews were, are and could again be a visible part of Moroccan society.

The museum is working to reconstruct a national identity for Moroccan Jews because this identity has faded. Contemporary Moroccan society predominantly views Moroccan Jews as foreigners, and unfortunately some members of the current generation have developed anti-Semitic views. I’ve selected a few items to analyze that reflect the intentions of the museum.

Emphasizing national identity and traditions in the museum

The contents of the 700-square-meter museum include a variety of sections. There are numerous pieces of metal work produced by Moroccan Jews, artifacts that belonged to synagogues, and different types of traditional attire for Jewish wedding celebrations.

Keswa lakira, velvet embroidered with gold thread, from 19th-century Marrakesh

Representations of traditional dress that appear throughout the museum demonstrate its narrative of national unity. Wedding ceremonies are a particularly special life cycle event that brings family members and different generations together.

Artifacts from weddings represent an important form of national unity, and exemplify the museum’s intention to show that Moroccan Jews embody the same traditional attire and customs as Moroccan Muslims. The chairs used in marriage celebrations, decorated with eight-pointed stars, and traditional Moroccan motifs and colors reflect the Moroccanness of the Jewish community.

Black velvet caftan embroidered with gold thread, from Fes.

The keswa lakbira (“big dress”) and the caftan offer an example of the traditional elements that have helped maintain the feeling of Moroccanness for Jews. The green velvet bridal dress is very unique to the traditions of weddings in Morocco, both in color and in the use of belts. The long shawl to cover the head and shoulders of the bride also signals a quintessentially Moroccan wedding celebration.

To the visitors of the museum, both foreign and local, the impact is significant. The clothes look identical to what any Moroccan Muslim bride would wear. The impact on Moroccan Muslim audiences, regardless of their generation, is a feeling of familiarity. It feels as if they are seeing themselves, creating a sense of mutual belonging of Jews and Muslims to the Moroccan nation.

Missing narratives: Migration and geopolitics

While the Museum of Moroccan Judaism provides a platform to join Arab, Muslim and Jewish groups into a unified Moroccan national identity, it also neglects the various historical narratives that divided those groups. The absence of narratives of everyday social and political life of Moroccan Jews from the museum seems to serve a purpose, portraying the nation as multicultural and pluralistic, without considering the negative and dark parts of its history.

Andre Levy’s book “Return to Casablanca: Jews, Muslims and an Israeli Anthropologist,” delves more deeply into the special history of Moroccan Jews in the 20th and 21st centuries, revealing an isolated existence for modern-day Jews in Morocco, and strained Jewish-Muslim relations that make a unified, multicultural Moroccan national identity uncertain. Still, while the museum represents a constructed, even artificial united national narrative, it supports the renegotiation of national identity for a critical purpose: to advance the incorporation of Jews into the past, present and future of Morocco.

Reviving a multicultural Morocco

Contemporary Morocco is grappling with its Jewish history. But organizations like FJMCH and Association Mimouna, a group of Moroccan Muslim students, have taken the initiative to rehabilitate and preserve Jewish traditions, history and memory in Morocco. They deserve recognition for commemorating the existence of Moroccan Jews and promoting coexistence.

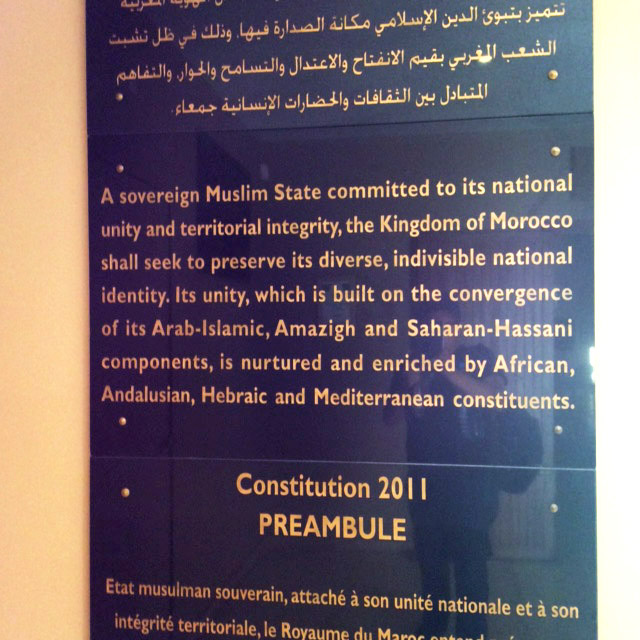

Museum plaque highlighting the 2011 Moroccan constitution preamble.

The modern Kingdom of Morocco is itself playing a major role in asserting the indigenous presence of Moroccan Jews, and in reconstructing a unified, multicultural national identity in contemporary Moroccan consciousness. In 2011, the Moroccan government enacted a new addition to the constitution, acknowledging Morocco’s “Hebraic” legacy alongside that of other ethnic groups. Still, the legacy of Jews’ forced migration from Morocco, and continuing anti-Jewish sentiments as a result of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, continue to influence the most recent generation of Moroccans.

While these continue to be difficult topics, there is a pocket of Moroccan Muslims who are working within civil society in to build stronger ties with fellow citizens (and former fellow citizens) of other faiths. In Fez and other cities, historic Jewish cemeteries and synagogues are guarded by Moroccan Muslims, and in Marrakesh, a revived Sephardi synagogue hosts local Moroccan Muslims for activities and community projects. In Casablanca, university students are researching Moroccan Muslim-Jewish relations.

Those involved in civil society initiatives that promote coexistence and integration, and those involved in research and initiatives like the Museum of Moroccan Judaism, are the future of a multicultural and pluralist Morocco.

Thank you to Kara Schoonmaker for exceptional support with the editing of this article, and to Dr. Kathie Friedman and Dr. Arzoo Osanloo for their input on the subject.

They deserve recognition for commemorating the existence of Moroccan Jews and promoting coexistence.