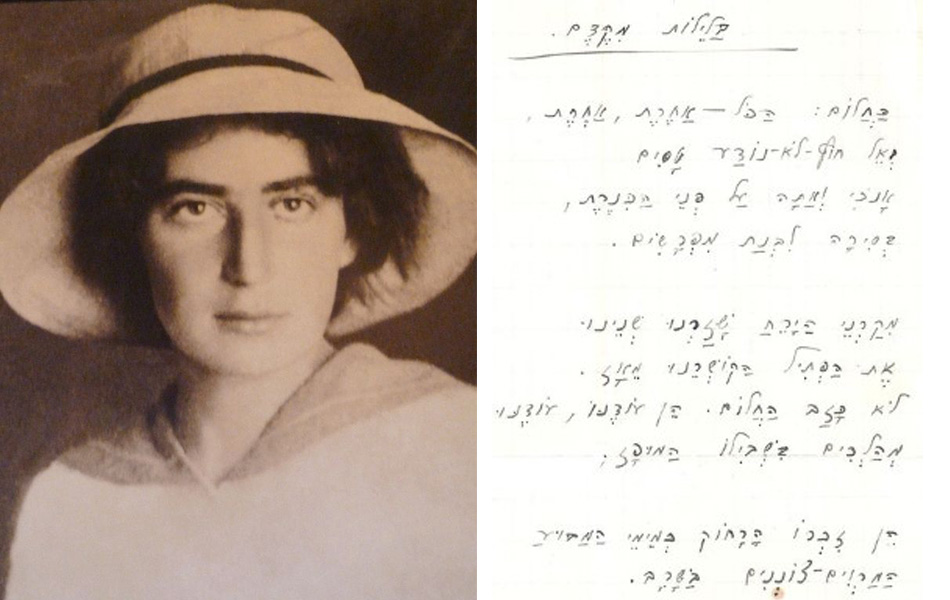

Poet Rachel Bluwstein (1890-1931), known as “Rachel” or “Rachel the Poetess,” alongside the manuscript for her poem “BeLeilot MiKedem.” Manuscript via the National Library of Israel.

By Adriana X. Jacobs

Reading my college senior thesis today is excruciating. It is a work of indecision by someone who wasn’t sure what she wanted to write about, who probably, had she been honest with herself, did not want to be writing a senior thesis. It offered a comparative reading of “narratives of interiority” in the work of the poets Alfonsina Storni (Argentina), Anna Akhmatova (Russia), and Rachel Bluwstein (Ottoman and Mandatory Palestine) but completely lacked focus and argument.

If I am still holding on to my only copy, it is only because it contains my first English translations of Hebrew poetry, a language I had started to study in my senior year. Naama Zahavi-Ely’s biblical Hebrew course was the only Hebrew language option at the College of William and Mary, and I was lucky that she generously offered to sit with me every week and read Rachel Bluwstein’s poetry.

To practice writing in Hebrew, I would transcribe a poem onto a sheet of paper, add the nikkud (vowel markers) by hand, and then translate each word using my Hebrew-English pocket dictionary. Then Naama and I would go over my very literal versions, line by line, while I made note of the (many) biblical allusions and cultural references that I had missed.

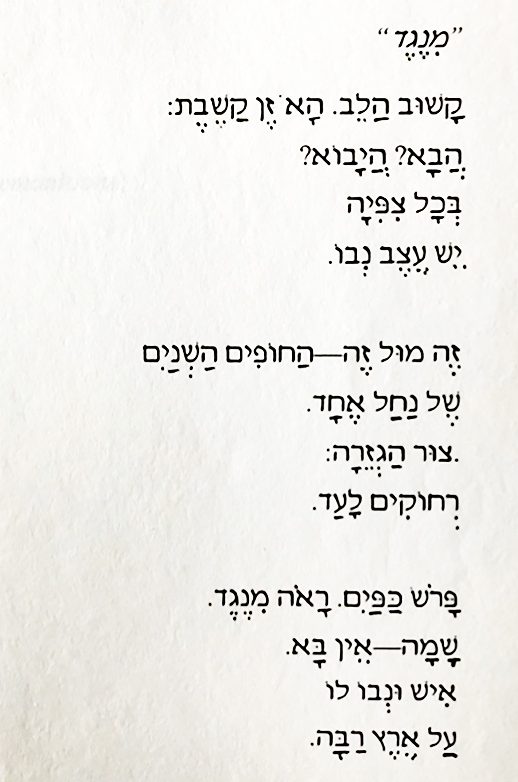

One of the poems I discussed in my thesis is “Mineged” (“From across”) from Rachel’s posthumous collection “Nevo” (1932). The title refers to the mountain where Moses was granted a view of a Promised Land that he was not allowed to enter. Rachel returns to this episode as a way of addressing, in part, the pain of separation from her beloved Degania, a kibbutz in northern Israel. She had contracted tuberculosis during World War I, which prohibited her from continuing to reside there, and for the remainder of her life she lived in and around Tel Aviv, eking out a living as a French and Hebrew language tutor. In fact, Naama’s grandmother Shulamit had been her doctor in those years.

“Mineged” (“From across”) in Hebrew

Take for example the first line of “Mineged,” which repeats the root ק-ש-ב (listen), calling attention to the poem itself as well as to its prosodic elements. The five-syllable hemistiches (half-lines) in my translation acknowledge the importance of rhythm in Rachel’s work, and rhythm is also something that I continue to prioritize in my translations. Today, I would recast this line so that it followed more closely the syllabic count of Rachel’s poem (4 and 6 syllables), and I certainly would change “all hope” to “every hope.”

Nevertheless, I appreciate how the translation reveals its own context; for instance, Ana María Bejarano’s 1985 Spanish translations of Rachel’s poetry were the only ones available to me at the time, and a trace of her Spanish remains in my transliteration of “Mineged” as “Minegued.”

While Bejarano’s translations are remarkable, they, as well as the English translations I have come across, tend to smooth out the more radical qualities of Rachel’s work: hyphens disappear, and with them Rachel’s sudden breaks and abrupt transitions; ironic metaphors read as sentimental; syntactical distortions turn fluid and grammatical.

My Hebrew was rudimentary, so I stayed close to the original text, carrying every ellipsis, hyphen, and period into the English. Sentence fragments remained broken like my own Hebrew. Reading the translation now, especially the line “in all hope/there is the pain of Nevo,” I recall how underlying my enthusiasm for Hebrew was the uncertainty of where it would take me. Was it just a phase? Or the beginning of a more lasting change in my life?

The image of the “two shores” in the second stanza also suggests translation, both in the movement from Hebrew to English and in the parallel work of approaching Hebrew comprehension.

Years ago, in a fit of cleaning, I threw out most of the paperwork related to my undergraduate years and with it my weekly translations of Rachel. Three poems in my senior thesis are all that remain of my first Hebrew translations.

I wouldn’t change a single word.

“Minegued”

“Minegued”

The heart is inclined. The ear, attentive:

Is he coming? Will he come?

In all hope

There is the pain of Nevo.

This one facing the other — the two shores

Of one torrent.

The cliff of separation:

Distant, forever.

To open the palms. To see from across.

There — no one comes.

A man and his Nevo

Over a great earth.

translated by Adriana X. Tatum (1998)

Adriana X. Jacobs is Associate Professor of Modern Hebrew Literature in the Faculty of Oriental Studies. She has published widely on contemporary Hebrew and Israeli poetry and translation, including articles in Shofar, PMLA, Studies in American Jewish Literature, and Prooftexts, as well as chapters in several edited volumes. Her translations of the American Hebrew poet Annabelle Farmelant appeared in “Women’s Hebrew Poetry on American Shores: Poems by Anne Kleiman and Annabelle Farmelant” (Wayne State UP, 2016). She is the author of “Strange Cocktail: Translation and the Making of Modern Hebrew Poetry” (University of Michigan Press).

Thank you for sharing your experiences. Yes, we can learn language by translating but becoming an expert is a different subject.

Lovely stories. What a great website honouring Hebrew and those who learn and teach it.

So… Nevo? No, in English it’s Nebo. As you yourself mentioned, it is a slightly older translation. So, you should actually consider the title, which is not “in front of ” but “from afar” or “across” (you may look in the NIV translation, as also in the KJV). Now, the most important misinterpretation of your translation is the second line. In the biblical text, it is ENTER – LO TAVO – in biblical Hebrew, which means to enter. Now the most important sound and rhyme your translation is oblivious to is for the ‘o’ that resounds the Hebrew “LO”- “TO HIM” OR “NO”. Or “you shall not go there” or “cross there”. I understand that you did this translation when you were young and not so fluent in Hebrew. As such, you deserve consideration; however, your translation does not deserve to be shown off because it testifies that you were ignorant of the Hebrew language and its biblical allusions as a child. To do justice to Rachel’s beautiful alterations, you should remove that translation.