A prison official featured in an Israeli newsreel clip reporting on the death sentence of Mahmoud Hijazi in 1965. Via the Israel Film Archive.

By Smadar Ben-Natan

The state of Israel has carried out only a single legal execution throughout its history: that of Nazi criminal Adolph Eichmann in 1962, 60 years ago. The exceptional character of that execution leads many to think that the death penalty in Israeli law is reserved only for Nazi crimes and is not otherwise legal. This public perception is both true and not true: the death penalty is legal in Israel, yet it is not used.

Since the Second World War, the global trend has shifted away from the death penalty, and many states have either abolished capital punishment altogether or refrain from using it. The United States remains as an outlier among democracies in its continued pursuit of executions, while Israel is a de-facto abolitionist state.

The brief look that I provide here into Israel’s history around the death penalty provides insights into the space between what socio-legal scholars call the “law in the books” and the “law in action,” and into connections between punishment, politics and history.

The history of the death penalty in Israel

Prior to Israel’s establishment, between 1922-1948 the British Mandate government in Palestine enforced the death penalty over both Arab-Palestinian and Jewish communities, under its Defence (Emergency) Regulations. In the 1930s, during the “Arab Revolt,” and in the 1940s, responding to Jewish underground movements like the Etzel and Lehi, Palestinian and Jewish militants were sentenced under these Emergency Regulations, which authorized the trial of civilians by military courts, where they could be condemned to death, and executed by the British government.

The founders of the state of Israel thus identified the death penalty with the oppressive rule of the Mandate government. During the 1948 war for independence, the Israeli military unlawfully executed Meir Tobianski, after a summary treason conviction by a makeshift court-martial. The unlawful execution was followed by a post-mortem exoneration of Tobianski, and served as another painful reminder of the flaws of the death penalty. Therefore, one of the first legal reforms that Israel introduced into British legislation was to abolish the death penalty for murder in 1954, replacing it with mandatory life sentence. However, the death penalty was not abolished for treason.

Israel also kept in place British emergency legislation – the Defense (Emergency) Regulations – that allowed for the death penalty to be imposed for national security offenses. Additionally, in 1950, Israel enacted the Nazi Criminals Prosecution Law, which prescribed capital punishment for Nazi crimes.

The death penalty was thus abolished for “ordinary” murder, but remained in the books for serious offenses related to the historical and political contexts of genocide, war and terrorism. When Israel occupied the territories of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip in 1967, the military law imposed in these territories also included the death penalty.

The death penalty and political violence

The main group that was considered a security threat to Israel was that of the Palestinians, either inside Israel or in neighboring countries. Palestinians were therefore the main group that was subject to the potential imposition of the death penalty under Israel’s emergency legislation.

But in Israel as well as in the occupied territories, executions have never actually been carried out as punishment for security offenses. The consistent position of Israeli governments, the military, and the security services has been to refrain from imposing the death penalty. The main reason given has been that executing offenders would not serve Israeli security interests: if executions were carried out, the condemned would be regarded as martyrs.

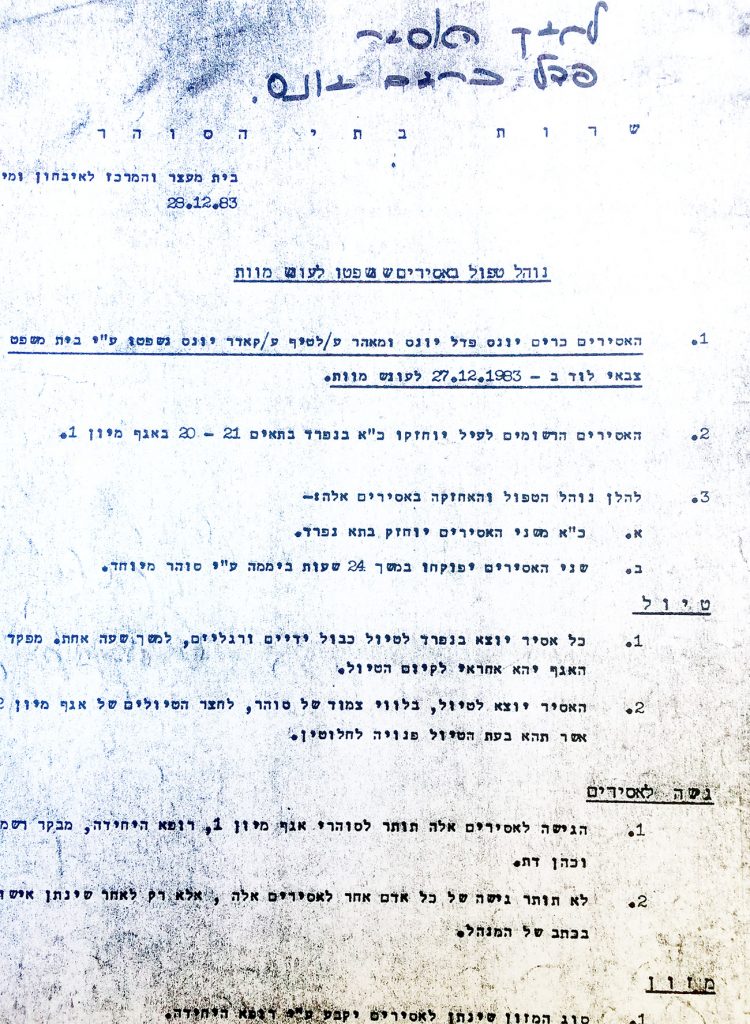

“Procedure for Treatment of Prisoners Sentenced to Death,” Israeli Prison Service document dated December 29, 1983.

What is the result of the difference between law and policy? Because the death penalty has remained legal, it has been possible for judges in Israeli military courts, authorized by the same British emergency regulations, to impose death sentences despite the government’s position. And indeed, on several occasions Israeli military judges have imposed the death penalty, opining that in the face of egregious terrorist attacks against Israelis they should follow the letter of the law and impose the ultimate punishment.

In 1965, for example, Mahmoud Hejazi, a Palestinian who crossed the border from Jordan to carry out an armed attack, was sentenced to death by a military court in Israel. In 1983, the Lod Military Court in Israel sentenced two Palestinian citizens of Israel, Kareem Younes and Maher Younes, to death for murdering an Israeli soldier. And in 1994, a military court in the West Bank laid down a death sentence on Sai’d Badarneh for organizing a suicide attack.

These death sentences have created confrontations between the Israeli legal system and the security establishment, which has always resulted in these sentences being overruled on appeal or commuted.

While these discussions were going on, those sentenced to death were treated as death row prisoners for as long as the sentence was valid, as this document of the Israeli Prison Service titled “Procedure for Treatment of Prisoners Sentenced to Death” shows. This push and pull in the legal system has left the shadow of the death penalty looming over the military courts and those accused in them.

Debates over the death penalty and the Holocaust

Amidst controversies over the death penalty, it seems like the execution of Nazi war criminal Adolph Eichmann should not have been controversial, as Eichmann was responsible for the transportation of millions of Jews to their deaths during World War II.

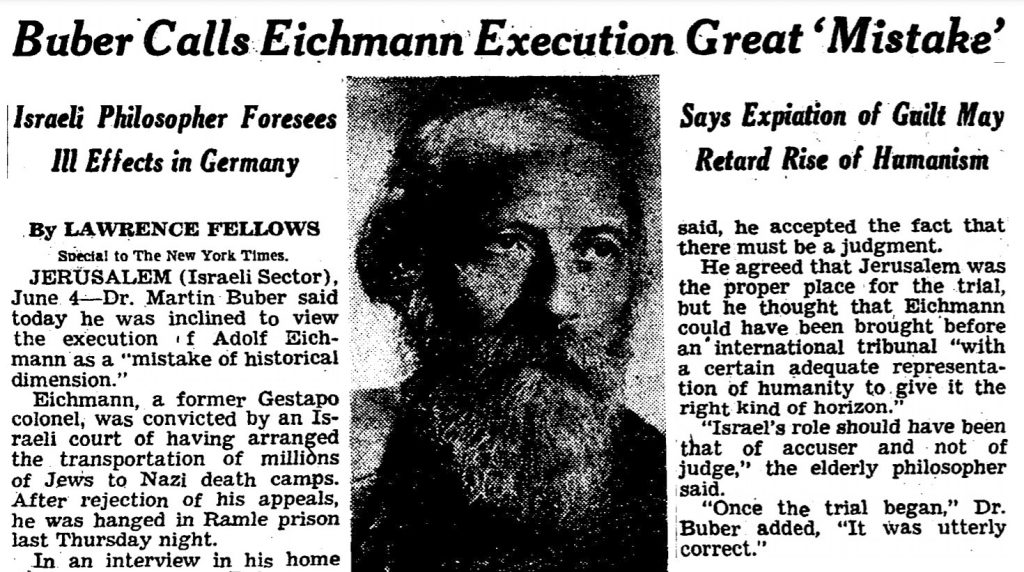

Interestingly enough, this was not the case: prominent Jewish intellectuals and philosophers such as Martin Buber and Gershom Scholem objected to the death penalty for Eichmann. They wrote to Israel’s prime minister, David Ben-Gurion, attempting to dissuade him from the execution. Buber’s position reached the pages of the New York Times, where he was cited after the fact as arguing that the execution was a “great mistake.”

Why would such intellectuals oppose the death penalty for a murderer of millions?

Headlines of the New York Times article about Martin Buber’s objections to the execution, June 5, 1962.

Neither Buber and nor Scholem had doubts about Eichmann’s guilt, nor did they have any mercy for him. But because of the exceptional and extraordinary nature of his crime, they thought that the traditional justifications for punishment – retribution and deterrence – did not apply.

They were concerned with a sense of historical justice: the crime was so immense that no punishment could offer retribution for it. They feared that an execution would create the impression that the process of holding accountable those responsible for the Holocaust had reached an end; that the account was settled. Since the lessons of the Holocaust were far from learned, they believed that appearance of justice being served could impede such a reckoning from actually taking place.

Scholem writes: “It will be said that the Israelis have captured the chief organizer of the murder; let them hang him and be done with it. […] One fears that instead of opening up a reckoning and leaving it open to the next generation, we have foreclosed it.”

Buber expressed a similar notion when he said, “Israel’s role should have been that of the accuser and not of judge.” Even the single execution of a mass murderer was fraught with controversy.

Ethical controversies over the death penalty: Challenging the victim-perpetrator dichotomy

Both of these controversies demonstrate the social and historical roles of punishment, beyond individual cases.

Buber and Scholem acknowledged the limits of criminal punishment in the face of the enormity of the Jewish Holocaust. The death penalty demonstrates these limits as the ultimate form of legal punishment, one that still remains pale in view of this historical atrocity.

Buber and Scholem seem to disfavor the role of the judge and executioner, for their violence and for their finite quality, and prefer the role of the accuser, which does not stain the moral stance of the victim with the violence of imposing punishment.

In the case of punishment for terrorism, again the ultimate punishment hits its limits. Because of the political aspect of these crimes, executed militants would be hailed as martyrs in their own societies and in the political arena. Martyrdom would also represent the reversal of the victim-perpetrator roles: the perpetrator of the terrorist action would be presented as a victim, and the state would be seen as an executioner — a different kind of perpetrator.

And so, while the Israeli state eventually chose the role of executioner in Eichmann’s case, it has never assumed the same role since then. This overview of the death penalty in Israel demonstrates that the death penalty remains highly controversial, even in a society that does not actually impose it. The shadow of the death penalty lingers in Israel as a contested issue involving core moral values, cultural concepts, and collective self-images of victim and perpetrator.

Smadar Ben-Natan is a longtime Israeli human rights lawyer who completed her Ph.D. in the Buchmann Faculty of Law, Tel-Aviv University. She specializes in law & society and international law, with a particular focus on the intersection of criminal justice, national security and human rights. She holds a Master in International Human Rights Law, with distinction, from the University of Oxford (2011), and an LLB from Tel-Aviv University (1995). She is the 2020-2022 Postdoctoral Fellow in Israel Studies at the University of Washington.

Smadar Ben-Natan is a longtime Israeli human rights lawyer who completed her Ph.D. in the Buchmann Faculty of Law, Tel-Aviv University. She specializes in law & society and international law, with a particular focus on the intersection of criminal justice, national security and human rights. She holds a Master in International Human Rights Law, with distinction, from the University of Oxford (2011), and an LLB from Tel-Aviv University (1995). She is the 2020-2022 Postdoctoral Fellow in Israel Studies at the University of Washington.

Leave A Comment