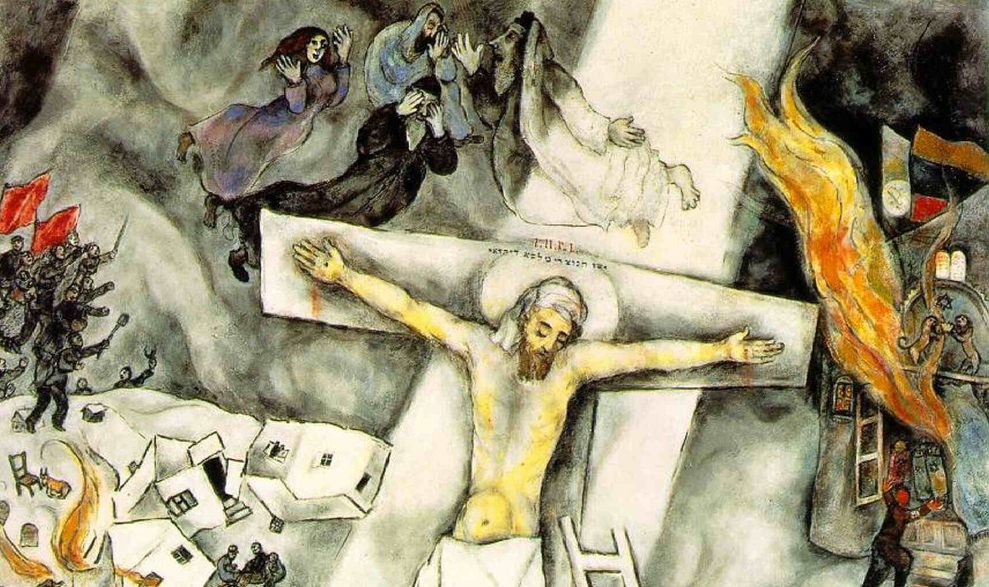

White Crucifixion, Marc Chagall.

By Mika Ahuvia

As scholar Annette Yoshiko Reed observed, to call the October 27, 2018, massacre at the Tree of Life Synagogue “anti-religious” is to erase the Jewishness of the victims and the anti-Jewishness of the shooter, “who quite explicitly rooted his hatred in his own Christian beliefs.”

It is time to confront the fraught Jewish and Christian history that has led to this moment. Recently in the Daily Beast, Candida Moss discussed how bigots exploited the Christian Bible to fuel anti-Semitism, focusing especially on the idea that Jews are Christ-killers and children of Satan.

Here I want to address another difficult issue that affects the way people discuss Judaism and the Jewish people: supersessionism, the dangerous idea that Christianity fulfills, triumphs over, and replaces Judaism. This doctrine was developed in antiquity and remains a lens through which Christians view Judaism. The continued existence of Jews and Judaism that belies supersessionism only encourages anti-Jewish vitriol.

Most of my students have no idea what the term supersessionism means, but that does not prevent them from engaging in supersessionist thinking without ill intention — and without even realizing it. They ask questions like: “But the God of the Hebrew Bible is an angry God, right?” Or they make statements like: “Judaism is a legalistic religion, it’s all about ritual, not a relationship with God;” “Christianity is a religion of love, Judaism isn’t.”

In supersessionist thinking, Judaism stopped developing in the first century CE and has remained stagnant ever since. Even students of Jewish backgrounds repeat these clichés, having internalized what the Christian majority says about them and their traditions.

Challenging clichés about the “Old Testament God”

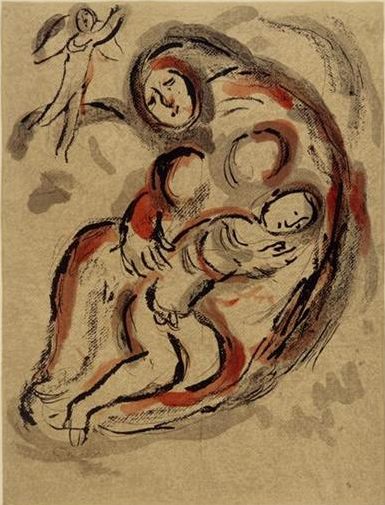

Hagar in the desert. Painting by Marc Chagall, 1960.

A close reading of the Hebrew Bible obliterates such supersessionist clichés. The entire narrative of the first five books of the Bible is about a God who is in search of a relationship with people. Over and over again, God reaches out, and humanity lets God down. But God perseveres, through Noah, Abraham, and his descendants. The Hebrew Bible offers the stories not only of Isaac, the promised child, but of Hagar, the lowly maid-servant without a home, who also happens to be the only woman in the Bible to see and name God (Genesis 16:13). In the biblical narrative, God finds Hagar and her son Ishmael in the desert, provides water for them, and comforts them.

Indeed, the New Testament does not have a monopoly on compassion for the lowly. Hagar’s son Ishmael, the forefather of the Arab people, is promised the same destiny as the forefather of the Israelites, Jacob. That story of equality between the descendants of Abraham is often forgotten and overshadowed by Paul’s retelling, which favors Isaac and displaces Ishmael. Also overlooked are the inspiring stories of Exodus, where the enslaved Israelites are liberated by God from slavery; the priestly ideals of Leviticus; the intimate relationship of God with Israelites in the wilderness in Numbers; and the culmination of biblical teachings in Deuteronomy.

The only biblically commanded prayer can be found in Deuteronomy 6:4, and is still recited by Jews today: “Hear, O Israel: The Lord our God, the Lord is one. And you shall love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your mind and with all your strength.” This prayer emphasizes the importance of a relationship of love with God.

Challenging clichés about Jewish legalism

In ancient times, Jewish interpreters such as the Pharisees developed liturgical ways of marking their devotion to God, grounded in the laws of the Torah and the example of the priests.

Some anti-Jewish sentiments are based on Paul’s description of Israelite practices in his Letter to the Galatians. We must remember that Paul never described himself as Jewish or Christian. The term “Christian” didn’t exist yet in his lifetime. And “Jewish”/”Judean” was what others called the people of Israel, not what they called themselves in that period. As far as scholars can tell, most Jews never experienced the law in the way the Apostle Paul (sometimes) describes it: in terms of guilt or enslavement to sin.

Jews all over the Mediterranean world impressed and intrigued Greeks and Romans with their devout devotion to an aniconic God, their dietary regulations, their Sabbaths, and their circumcisions. Through these rituals, Jews celebrated ongoing interaction with God. If ritual was a mode of paying attention, the ancient Jews had figured out myriad ways of paying attention to God.

That’s why the Jewish way of life was so attractive to others, and why Paul railed against gentiles adopting the Law (i.e. the Torah) in the Letter to the Galatians. Paul believed that the Torah and its way of life was for Jews; for gentiles, there was a new way to salvation, one through faith in Jesus, a way that did not require circumcision, Sabbath, and kashrut, Jewish dietary observances (on which, see “New Perspective on Paul,” John Gager’s “Reinventing Paul,” or his recent book “Who Made Early Christianity? The Jewish Lives of the Apostle Paul”). Paul argues so adamantly about his position precisely because these rituals — and the communities they engendered — must have been appealing to the recipients of his letters.

Challenging the mindset of “us vs. them”

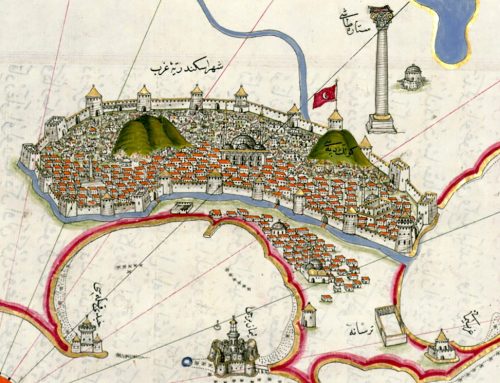

Woodcut from the “Nuremberg Chronicle” (1493) showing villainous Jews being burned alive.

As I tell my students, it might seem easier to understand the world in terms of binaries like Christianity/Judaism, good/bad, love/anger, wrong/right, chosen/rejected, but these binaries are not rooted in truth, nor are they rooted in history. To understand Judaism, Jewish practices, and Jewish beliefs in terms of a binary with Christianity and Christian beliefs is fundamentally wrong. Through the centuries and in America today, it has proven dangerous as well. Medieval imaginings of the blood-thirsty, wretched Jews, guilty of the murder of Jesus, provoked countless expulsions, pogroms, blood-libels, and genocides.

It was only after the Holocaust that scholars acknowledged that supersessionist thinking permeated the study of Judaism and had violent real-world implications. After World War II, religion departments in America began reframing the relationship of Judaism and Christianity as sibling religions that parted ways in the first century CE. Around this same time, as Americans reacted to the horrors of the Holocaust and defined themselves against the atheism of Communist Russia, the term “Judeo-Christian” was popularized. This has proven to be a fragile term, poorly papering over differences that were never fully confronted.

That hyphenated link is now fraying as a certain segment of Americans define themselves against an imagined Other, the Jew, once again. Jews are once again serving as a useful foil and are being demonized once more in this polarized and poisoned political climate. Old anti-Semitic clichés are in political campaigns again: Jews, a tiny minority spread throughout many countries, are somehow in control of the media, government, and banks and are looking to overthrow white Americans with their globalist and cosmopolitan interests.

“Jews will not replace us,” the white nationalists at Charlottesville chanted last year, alluding to the anti-Semitic conspiracy theory that Jews are responsible for the social movements of the 1960s that toppled white supremacists from power. The shooter at a Pittsburgh synagogue targeted local observant Jews because he saw the world in terms of “us” and “them”: “us” being white Christian Americans, and all Jews, refugees, and people of color as “invaders” unworthy of life.

It was the approach of the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society (HIAS) to refugees that set the Pittsburgh terrorist off. HIAS and many Jewish Americans refuse to see the world in terms of “us vs. them.” In the words of HIAS’s president Mark Hetfield, “We used to welcome refugees because they were Jewish. Today HIAS welcomes refugees because we are Jewish.” To understand what Mr. Hetfield meant, we must to turn to the biblical sources.

Loving the other in Judaism and Christianity

“The stranger who resides with you shall be to you as one of your citizens; you shall love him as yourself, for you were strangers in the land of Egypt: I the LORD am your God.” (Leviticus 19:34). Today, many Jews — including me — understand refugees to be strangers, much as the ancient Israelites were strangers in the land of Egypt, driven there by famine and dependent on the kindness of others. The anthropologist Mary Douglas made a compelling case that the very center of the book of Leviticus can be found in a related statement in verse 18: “You shall love your fellow [or neighbor] as yourself.”

Most Christians do not realize that Jesus is quoting Leviticus in Mark 12:28-31 when a scribe asks him, “Which commandment is the most important of all?” and Jesus answers, “The most important is, ‘Hear, O Israel: The Lord our God, the Lord is one. And you shall love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your mind and with all your strength.’ The second is this: ‘You shall love your neighbor as yourself.’ There is no other commandment greater than these.”

We might compare this with a conversation a gentile had with one of the leading interpreters of the Torah in the first century CE. When asked to summarize the teachings of the Torah, the famous sage Hillel answered: “What is hateful to you, do not do to your neighbor, that is the entire Torah, the rest is commentary, go study” (Babylonian Talmud Shabbat 31a).

These sayings pose a different kind of binary relationship between the self and one’s neighbor or fellow human being, where the relationship is not one of replacement (or us vs. them), but one of ongoing interaction: love the other, do not hate the other.

“The ways that never parted”

More recently in religious studies, scholars have reframed the relationship of Judaism and Christianity again. Instead of “the ways that parted,” now we discuss “the ways that never parted.” This paradigm acknowledges that many varieties of Judaisms and Christianities thrived in antiquity and that we cannot point to an exact time or place where these communal boundaries were established. Instead, these Jewish and Christian communities continued to overlap and share much in common, only slowly establishing their boundaries, and defining themselves through each other for centuries. This is a process that continues today.

It comes down to this: Christians read the Old Testament through the New Testament. For them, the Hebrew Bible is incomplete. For Christians, Judaism might seem incomplete.

For Jews, the teachings of the Hebrew Bible stand on their own, without Jesus. For Jews, the New Testament can be read as an intriguing document, a record of how some Jews understood themselves in the first century CE. As a scholar, it is an ancient text that I cherish alongside many others, even as I do not feel its pull theologically.

Christians must have the confidence in their own faith without needing to make Judaism wrong. And Jews, too, can have confidence in their own traditions, without needing to justify themselves to Christians. The other will remain other, but we have the choice of choosing between love or hate as our point of departure. I hope we choose to follow the best insights of our shared religious traditions and choose to see each other’s fundamental humanity first. The rest is commentary. Let’s study.

Further Reading

- An English professor reflects on Pittsburgh by Joe Butwin (2018)

- The United States should embrace its legacy of compassion towards immigrants and refugees, not its history of xenophobia by Kathie Friedman-Kasaba (2018)

- A Jewish historian’s plea for global refugees by Mika Ahuvia (2015)

Fear seems to be the core of some Christian teachings coming forward through the filter of many interpretations. We should all be lucky enough to have purer guidance, untainted by a bad day, an angry week, a stressful month, a grudge or a horrific experience that dwells deeply inside. We should all be open minded enough to hear and learn the best which might arm us to weather the rest. Thank you for this.

Thank you, Mika, for your thoughtfulness. As a Christian but also a Jew by blood, I have been alarmed by the subtle anti-Semitism that I have run into in some Christian circles. I have also been encouraged by Israeli support in other Christian circles. Though I believe Yeshua/Jesus is the fulfillment of the Old Testament prophecies about the Messiah, I have much respect for my Jewish friends and appreciate your research and study and look forward to reading your other articles. As a side note, I participated in the 2010 Tel Dor, Israel, archeology dig with UW Prof. Stroup and have a deep love of Jewish archeology as well. Blessings to you.

I understand you don’t like anti-semitism, and that’s good. But if Christianity is true, every other religion is not from God (except Judaism in the past). If Judaism as it is now is still true, then every other religion is not of God. Saying we don’t need to justify ourselves is not a good solution. God does not want us worshipping other gods or even having misconceptions about His nature. It sounds pluralistic, and the shema excludes pluralism. Either Christians are wrong or Jews are wrong.

The Shema is taken directly from the Bible, my friend. Deuteronomy 6:4-5. However, Judaism does not necessarily claim to have a monopoly on truth. Others which follow the Seven Laws of Noach are righteous and have a place in the world to come, and the Torah is binding only to the tribes of Israel. Now, who can know G-d fully in this life? What matters is that we do what He wants us to do.