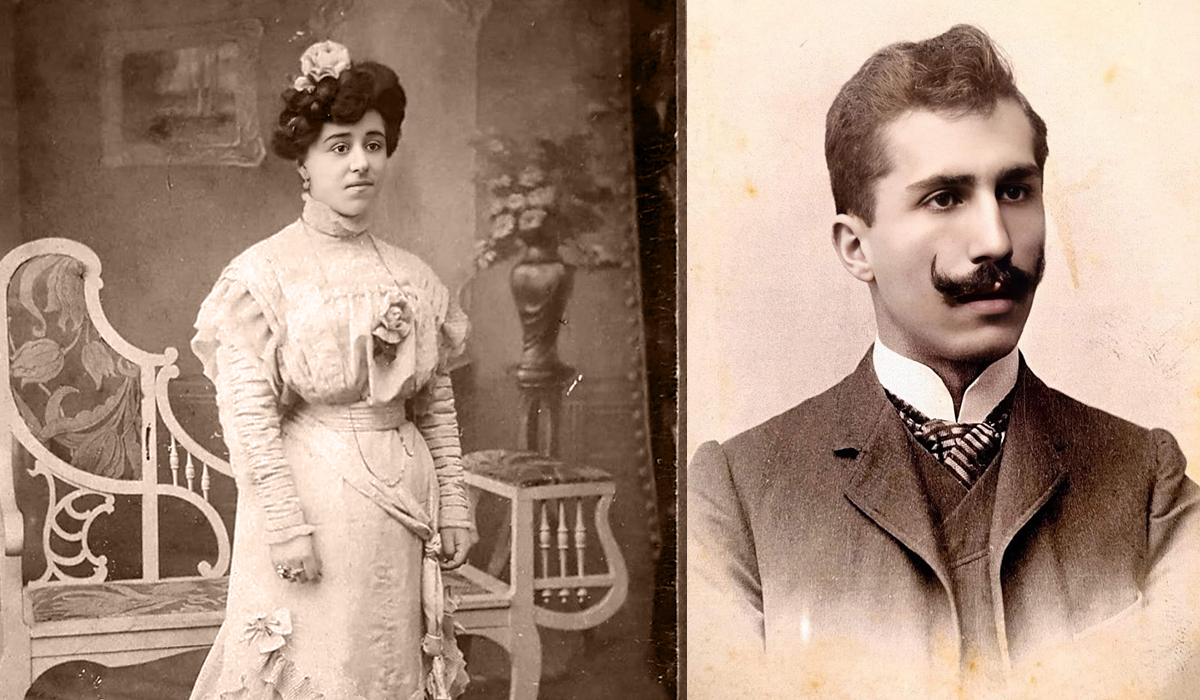

Photos of the interviewee’s great-grandmother and great-grandfather, taken in Salonica. From the interviewee’s family collection. Permission given to the author for publication.

By Sasha Marie Ward

In 2015, both the Spanish and Portuguese governments passed bills granting citizenship to the descendants of Sephardi Jews who can trace their ancestry back to the Iberian Peninsula, where present-day Spain and Portugal are located. The legislation serves as an apology for the persecution and subsequent expulsion of these Jews during the Spanish Inquisition during the fifteenth century.

The Spanish legislation was one of the most significant developments in the question of Jewish citizenship since Israel’s Law of Return in 1950, which promises Israeli citizenship to anyone who has documentary evidence of at least one Jewish grandparent. This change began new and important conversations about the legacy of the Spanish Inquisition and the possibilities for Jewish citizenship in the modern era.

In countries like Turkey with notable Sephardi Jewish populations, independent researchers with knowledge of Sephardi genealogies help to prepare the necessary documentation for such passport applications for members of the community. One such individual is Selim Kaya (name changed to protect anonymity), who I had the opportunity to meet during my dissertation fieldwork in Turkey, whose story demonstrates the complexity of Sephardi Jewish belonging in the twenty-first century.

Born to a Turkish father and American Protestant mother, Kaya resided in Istanbul, Turkey, until age eight and a half, at which time his family relocated to the United States. It was during this time, when Kaya turned nine years old, that his father disclosed a family secret: his father’s family belonged to the Kapancı Dönme (Turkish for “those who turn”), a crypto-Jewish sect with origins in seventeenth-century Izmir (in present-day Turkey) that had followed Sabbatai Sevi, the self-proclaimed mystical Jewish messiah, in his conversion to Islam.

Who are the Dönme?

Portrait of Sabbatai Sevi. From a book published in 1667 about Sabbatai Sevi.

When Sabbatai Sevi – the self-proclaimed mystical Jewish messiah from Izmir – converted to Islam in 1666 under pressure from Sultan Mehmet IV, many of Sevi’s believers followed suit. These converts, who came to be known as Dönme, developed their own unique secret messianic subculture, later fragmenting into three subsects (Yakubi, Karakaş, and Kapancı).

Originally a group of about two hundred families that grew to between three and five thousand individuals by the turn of the nineteenth century, Dönme followed Sevi’s Eighteen Commandments, practiced endogamy (marrying within one’s community), and established their own educational institutions. They also formed justice systems, philanthropic organizations, and trade networks that expanded beyond the Mediterranean into western Europe and North and South America.

In metropolitan centers such as Salonica, an important port city on the Aegean Sea in present-day Greece, the Dönme – in part due to their outward Muslim identities – rose to the highest positions in the Ottoman administration, recognized widely for their roles in trade and finance, banks, commercial houses, and the textile trade. In these roles, Dönme had regular contact with unconverted Sephardi Jews, from interactions between Christians, Jews, and Muslims in Salonica’s Masonic lodge social clubs, to their alleged participation in 1908 in the bourgeoning Committee of Union and Progress (CUP), a political organization responsible for the Young Turks Revolution. It is for this reason that the Dönme have, for a century, been depicted as a politically subversive and conspiratorial group responsible for the collapse of the Ottoman Empire.

Following the population exchange between Greece and Turkey in 1923, in which Greek Orthodox Christians in Turkey were forcibly resettled in Greece and Turkish Muslims were returned to Turkey, the Dönme relocated to cosmopolitan centers like Istanbul. With the implementation of Turkification policies after 1923, which sought to assimilate non-Muslim minorities to a secular Turkish identity, Dönme cultural institutions slowly eroded. Communities that were once robust began to intermarry with non-Dönme people, assimilate into the culture around them, and thereafter to disintegrate as a distinctive ethnic group.

Today, there is a new generation of Dönme that is actively working to preserve their unique cultural and religious heritage from erasure — including independent researchers like Kaya with extensive access to genealogical documents and community archives.

Kaya’s Kapancı Dönme heritage — as a Selanikli, meaning “of Salonica,” as he describes himself — is a case study in the limitations of strict categorizations of Jewish identity in the modern era.

Who defines “Jewishness” in the modern era?

My research interests and dissertation work converge at the intersection of Sephardi Jewish culture, Ottoman history, and the political implementation of antisemitic conspiratorial rhetoric at the turn of the twentieth century, making Turkey’s Dönme community a paradigmatic example of the diversity of Sephardi experiences to be found beyond standard Judaism. My work also offers important insights into issues of belonging for non-standard Jewish groups in the era of nation-states and national citizenship.

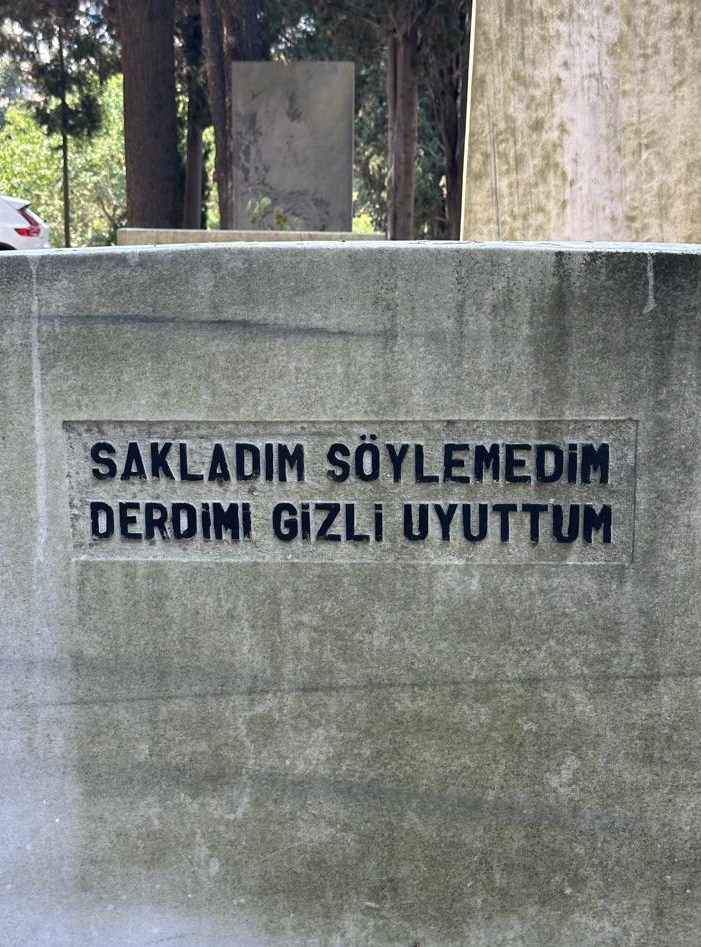

Inscription on the back of a headstone in the Karakaş section of Bülbülderesi Cemetery in Istanbul, where the majority of the Dönme community’s deceased are put to rest. The inscription reads, “Sakladım söylemedim derdimi gizli tuttum uyuttum” (“I hid my anguish inside, I did not tell anyone, I kept it a secret, and put it to sleep”). Photo courtesy of the author.

After learning of his Dönme heritage, Kaya spent his formative years studying Jewish culture and history, making the formal decision to convert to Judaism in his late twenties. Because of his connection to the Kapancı Dönme community, Kaya had come into possession of several documents that demonstrate his family’s Sephardi Jewish ethnic ties to the Iberian Peninsula, which, he believed, would prove his Jewish heritage and facilitate his official conversion to Judaism in Turkey. (These same documents would facilitate Kaya’s Portuguese citizenship, which he acquired in 2018.)

However, Kaya was disappointed when he went to meet with the Chief Rabbinate of Istanbul, who was unwilling to perform the conversion out of fear of the potential backlash from the Turkish government. In recent years, Turkey’s Jewish communities have been subjected to antisemitic violence, such as the 2003 bombings of Istanbul’s Neve Şalom and Beth Israel synagogues, killing twenty-four and leaving more than three hundred people injured. Were the general public to believe that the Chief Rabbinate were “converting” citizens, legally classified as Muslims by the Turkish state, to Judaism, they feared that there could be severe implications for the protected status of the Jewish community.

Upon encountering this roadblock, Kaya took the advice of a friend to travel to Israel, attend a yeshiva (religious school), and find a rabbi to sponsor his conversion there, with the hopes that after appearing before the beit din (religious court) in Israel, he could demonstrate this official recognition of his Jewishness to the Turkish Chief Rabbinate and thereby circumvent the political difficulties of conversion in Turkey. So, Kaya flew to the city of Efrat in Israel, and began to study at an English-speaking yeshiva to continue his studies.

There, Kaya did manage to find a rabbi willing to oversee this process — an American one at that — but Kaya’s father fell ill and he had to return to Turkey after just two months abroad. To help rectify the situation, the American rabbi wrote a letter detailing the plan to facilitate Kaya’s conversion to Judaism in Israel, requesting that the Chief Rabbinate oversee his Jewish learning in Turkey in the meantime; the Chief Rabbinate accepted this proposal, agreeing to one-on-one meetings with Kaya to move him along towards conversion.

Yet, Kaya found that while the Chief Rabbinate was amenable to this process on paper, they were less so in practice. After just two lessons, Kaya found that the Turkish rabbi found an excuse to cancel their meeting each week, and Kaya realized that there would be no path forward in Turkey to formally convert to Judaism.

This process would be further complicated by the fact that, because of the widespread perception that Kaya’s ancestors had willingly converted to Islam — rather than be forcibly converted, as was mostly the case with converso Jewish communities in the Iberian Peninsula — the Israeli beit din did not consider Kaya to be Jewish, in compliance with the 1950 Law of Return.

Furthermore, Kaya was only half Dönme, on his father’s side, which made halakhic rulings on this issue all the more complicated. And even if Kaya’s ancestors had unwillingly been converted to Islam, Kaya’s mother was an American Christian, and therefore, Kaya could not be considered Jewish through matrilineal descent; the “un-kosherness” of Kaya’s Dönme identity, as a result, became a secondary issue.

So, Kaya decided to pursue another path towards formal recognition of his Jewishness: to formally convert to Orthodox Judaism in the United States, which would be legally ratifiable in both Israel and Turkey. This path, however, would require a disproportionate amount of time that Kaya didn’t have, given his father’s continuing illness. And so, Kaya remained in Turkey, waiting for an opportunity to return to the Judaism he feels himself to be so much a part of.

At the same time, Kaya was not denied all recognition by the Chief Rabbinate: Upon one meeting with the Turkish rabbi before Hanukkah, Kaya wished the rabbi farewell and chag sameach (in Turkish, bayramınız kutlu olsun, or “may you have a happy holiday”). In response, the Turkish rabbi — though still unwilling to oversee his conversion — responded with an unexpected level of friendly validation: “Selim, may we have a happy holiday.”

Challenges for the “in-between” descendants of formerly Jewish communities

Stuck in the liminal space between Islam and Judaism, Sephardi and Kapancı Dönme, Kaya’s story is illustrative of the problems facing popular conceptions of Jewishness today, as well as limitations on who can be defined as Jewish — thus forcing us to grapple with the legacy of the diaspora’s formerly Jewish communities and their inclusion in Jewish society today, particularly in countries where the boundaries between these identities have been blurred.

Sasha Marie Ward is a second-year doctoral student in the Near and Middle Eastern Studies Interdisciplinary Ph.D. program. Sasha’s research focuses on conspiracy theories about Jews in late-nineteenth and early-twentieth century Ottoman Istanbul, specifically looking at perceptions of Jews as collaborators with global socialism, Western capitalism, and American imperialism. Her work also examines conflations of Dönme (a crypto-Jewish sect originating in seventeenth-century Izmir) and normative Jews as sources of conspiracy in contemporary Turkish politics. Before coming to the University of Washington, Sasha attended culinary school at Mutfak Sanatları Akademisi in Istanbul and worked as a pastry chef in San Francisco. Outside of academia, Sasha is an avid weightlifter and literature enthusiast, and loves to go on hikes with her pet corgi, Kimchi.

Sasha Marie Ward is a second-year doctoral student in the Near and Middle Eastern Studies Interdisciplinary Ph.D. program. Sasha’s research focuses on conspiracy theories about Jews in late-nineteenth and early-twentieth century Ottoman Istanbul, specifically looking at perceptions of Jews as collaborators with global socialism, Western capitalism, and American imperialism. Her work also examines conflations of Dönme (a crypto-Jewish sect originating in seventeenth-century Izmir) and normative Jews as sources of conspiracy in contemporary Turkish politics. Before coming to the University of Washington, Sasha attended culinary school at Mutfak Sanatları Akademisi in Istanbul and worked as a pastry chef in San Francisco. Outside of academia, Sasha is an avid weightlifter and literature enthusiast, and loves to go on hikes with her pet corgi, Kimchi.

Spain is now putting obstacles to Jews wishing to obtain Spanish citizenship. The process has slowed down to almost a halt.