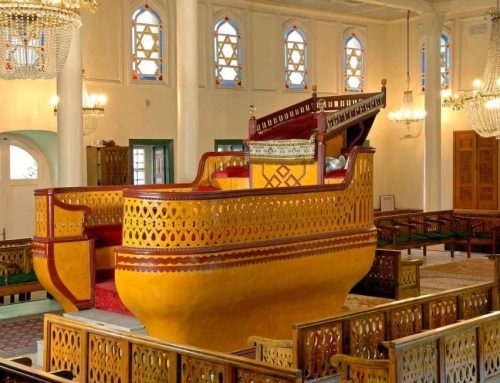

Banner for L’Aurore, an Ottoman Jewish newspaper. January 29, 1915. Via the National Library of Israel.

By Büşra Demirkol

The Ottoman Empire — the state created by Turkish tribes in Anatolia that spanned between the years 1299-1922 — was home to many successful Jewish medical professionals over time, including figures such as Hamons, Hayatizâdes and de Castros. Yet, this essay is not about heroic Jewish physicians in the imperial court.

It is about a Jewish, feminist gynecologist who chose to live in the Ottoman capital, Istanbul, near the end of the imperial era in the late 19th century, and was, perhaps, too ahead of his time to be recognized as an important figure in historical accounts.

Why move from Europe to the Ottoman Empire?

Dr. Jean Miclesco was born to a Jewish family in 1861 in the capital of present-day Romania, Jassy. Determined to escape his parents’ insistence that he pursue a religious education, he emigrated to Germany. There, he studied medicine at the University of Munich and specialized in gynecology and obstetrics. Following his graduation in 1887, he embarked on a second migration, ultimately settling in İstanbul — the capital of the Ottoman Empire — where he dedicated 45 years to the active practice of medicine.

Although we do not know for certain why Miclesco decided to make İstanbul his home, despite professional and multilingual abilities compatible with work in any European capital, it is possible to deduce an answer based on a report on Romanian Jews published in The Reform Advocate – a newspaper published in Chicago “in the interest of Reform Judaism” – in 1907.

In the article, Max Sylvius Handman, a Romanian Jew who immigrated to the United States and later became a sociology professor, writes that Romania’s “Jewish problem” was only a part of “many neglected, unsolved and hopelessly entangled social problems” in the region. In Romania:

Jews cannot own any rural property, a Jew can’t teach any public school, a Jewish lawyer is not admitted to the bar, the Jew can occupy no governmental office of any kind and under any condition… Jewish physicians are not admitted to serve in non-Jewish hospitals, nor are Jews allowed to own or operate drug stores.

Considering the antisemitic, precarious conditions that Romanian Jews faced, Miclesco’s decision not to stay in Europe or return to his hometown in Romania may not be surprising.

Successful career in Istanbul; volunteer and literary work

As a physician, Dr. Miclesco had a thriving career within Jewish and Ottoman imperial institutions and attained high positions, such as chief surgeon of the military hospital in Istanbul. It is possible to glean his professional trajectory through Ottoman Jewish sources; on January 29, 1915, the newspaper L’Aurore announced that he had been selected as a board member of the Association of Jewish Physicians of İstanbul.

The Or Ahaim Jewish Hospital in Balat, İstanbul. Via the History of Istanbul website

From medical advertisements in the same newspaper, we learn that Miclesco had seen patients free of charge in the Or-Ahaim Hospital, the most prominent Jewish community hospital in Ottoman İstanbul, which is still open today. Last but not least, Miclesco also worked in an independent clinic, where he accepted patients from all ethnic and religious identities and classes.

In addition to his medical work in different institutions, Miclesco was also a prolific literary man. He wrote on various subjects, including philology and mythology, and even undertook a translation project of the poetry of medieval Sephardic intellectual Judah Halevi.

Feminist writing

Among these multilingual and multifaceted literary works, his most interesting ones were focused on women and gender. Particularly in his unpublished memoir (excerpted online here in Turkish), “La Vie et La Mort,” Dr. Miclesco sheds light on the under-discussed topics of female sexuality, pregnancy, abortion, and prostitution through the stories he witnessed while working in different gynecology clinics in 19th- and early 20th-century Istanbul.

Jean Miclesco, April 1917, Istanbul. Image via İrvin Cemil Schick.

While heavily inspired by his professional life and medical observations in the Ottoman Empire, Miclesco didn’t only write about Ottoman women. He also provided strong critiques of patriarchy across other societies, especially in Europe. According to Miclesco, “One of the greatest errors committed by the human spirit is to give the Church the authority to deal with the sexual question, to think that sexual morality depends on religion.”

In contrast to the morality of Christian theologians, who “constantly fix their eyes on the heavens while forgetting what is on the ground,” he defended the naturalness and legitimacy of female sexual desire: “A woman is not only a moral and social being but also a sexual being. To say that a woman must forever retain the purity of a virgin is like talking about fish that can live outside of water.”

Another aspect of women’s rights that Dr. Miclesco fervently defended was abortion:

It is no longer a question of enumerating the diseases that justify an abortion intervention, or of determining the moral qualities of abortion, but of emphasizing the fundamental fact that the woman has the right to accept or refuse any operation. She is always the owner of her own body.

He also criticized the criminalization of abortion in penal codes such as those of the French, German, Austrian, and Ottoman governments, arguing that while the tiny fetus was protected, the female citizen’s right to life was effectively denied by state oppression. Dr. Miclesco’s unwavering support for women’s right to abortion, especially in a historical context where it carried severe penalties, was a bold feminist stance.

Beyond his memoir, the book in which Miclesco collected his feminist ideas on women’s bodies and sexuality, “Ecce Mulier ou L’Éternelle Blessée” (“Behold the Woman, or the Eternally Wounded”), was published in Paris in 1911, and brought him well-deserved international recognition.

It was reviewed and publicized in various Jewish, Ottoman, and French newspapers, such as Le Messager de São Paulo, Le Jeune-Turc, and La Lanterne. However, the most validating recognition for his work came when it was recommended in the feminist bibliography in the French suffragettes’ weekly newspaper La Française: Journal de Progress Feminine in 1923.

A feminist doctor ahead of his time

Dr. Jean Miclesco’s life and work embody a unique blend of medical expertise and a feminist perspective. He viewed medicine not merely as a profession but as a lens through which to understand societal and moral constructs related to women and sexuality.

As Miclesco himself noted, “In the course of my work in the art of medicine, I have often witnessed horrors and agonies that have led me to study the question of sex with complete independence and enthusiasm. It is from this extensive study that I have come to recognize the daily errors, abuses, and crimes committed by society in the name of morality in general and sexual morality in particular.”

As a Jewish, feminist gynecologist in late 19th- and early 20th-century Ottoman Istanbul, Dr. Jean Miclesco’s dedication to women’s health and his forward-thinking views on sexuality and gender issues positioned him as a unique figure who was ahead of his time in both Jewish and Ottoman histories. By advocating for women’s rights and demonstrating solidarity with female patients of all religious and class backgrounds, Miclesco made a mark on the medical field and on feminist thought.

His story serves as a testament to the diverse and impactful roles that Jewish physicians played in the Ottoman society, and his independent spirit continues to inspire research in both women’s and gender studies.

I am deeply grateful to Professor Irvin Cemil Schick, whose scholarly generosity and work made it possible for me to become acquainted with Dr. Miclesco’s legacy.

Büsra Demirkol is a Ph.D. candidate in the Interdisciplinary Program in Near and Middle Eastern Studies at the University of Washington. She received her B.A. in sociology at Galatasaray University and her M.A. in Turkish Studies and History at Sabancı University. Her master’s thesis focused on modernization in the legal field during the late Ottoman era and its impact on women on the margins. Based on penal codes, codification discussions, and court records, she traces how marginal women have been redefined and constructed within the boundaries of the public sphere in Ottoman legal culture and have been subjected to state intervention according to a modern understanding of crime and punishment. Before graduate school, she also worked as a social worker with African, Afghan, and Syrian refugees in Istanbul and researched the official and unofficial schooling of Syrian children. Her research interests include 19th-century Ottoman social history, sociological theory, history of medicine, and women, sex, and gender. She is a 2023-2024 Robinovitch Family Fellow in Jewish Studies.

Büsra Demirkol is a Ph.D. candidate in the Interdisciplinary Program in Near and Middle Eastern Studies at the University of Washington. She received her B.A. in sociology at Galatasaray University and her M.A. in Turkish Studies and History at Sabancı University. Her master’s thesis focused on modernization in the legal field during the late Ottoman era and its impact on women on the margins. Based on penal codes, codification discussions, and court records, she traces how marginal women have been redefined and constructed within the boundaries of the public sphere in Ottoman legal culture and have been subjected to state intervention according to a modern understanding of crime and punishment. Before graduate school, she also worked as a social worker with African, Afghan, and Syrian refugees in Istanbul and researched the official and unofficial schooling of Syrian children. Her research interests include 19th-century Ottoman social history, sociological theory, history of medicine, and women, sex, and gender. She is a 2023-2024 Robinovitch Family Fellow in Jewish Studies.