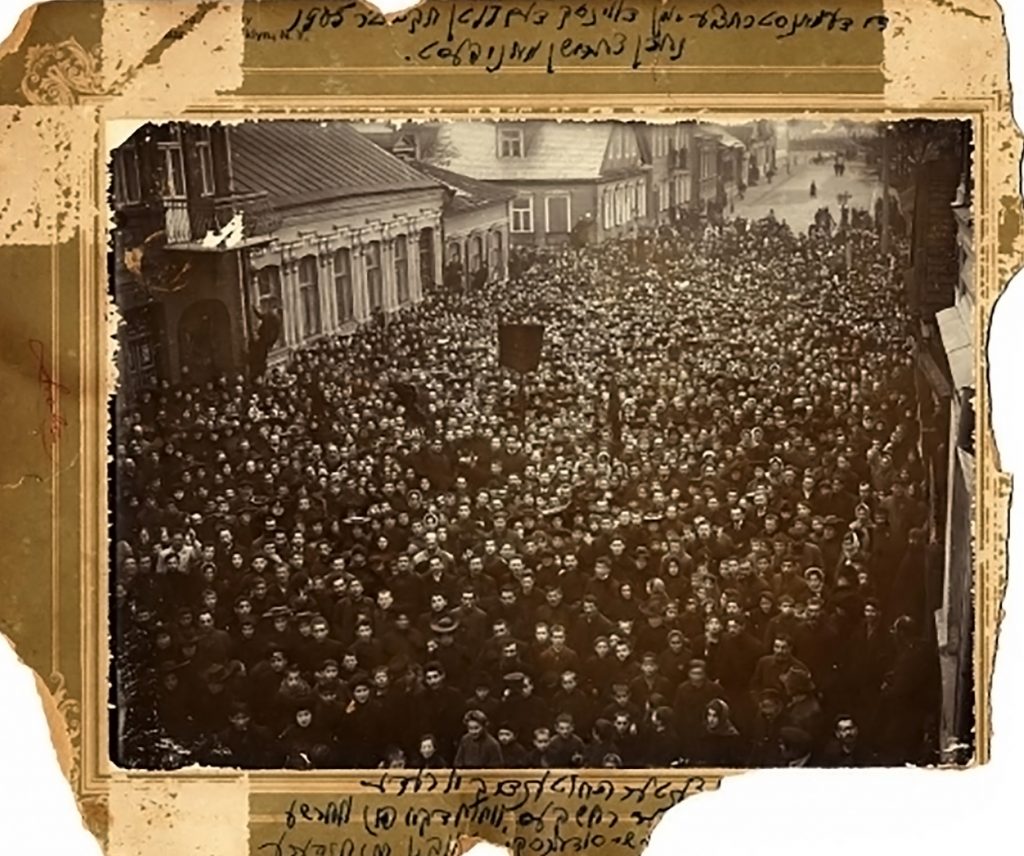

Members of the Bund on a picnic, Minsk, 1910. Via the YIVO Encyclopedia.

By Shelby Handler

“There, where we live, that is our country.”

— Motto of the Jewish Labor Bund

At this point, it is impossible to count how many times I have googled a phrase that began with the question, “What is the Jewish custom for…”? Each time I’ve typed my queries, I’ve always found a strange sense of belonging when my question immediately pops up as a suggestion, blinking in gray below the search box.

But what does my absurdly millennial and mundane strategy for accessing ancient, sacred Jewish practices have to do with my graduate research on the General Jewish Labour Bund, the largest Jewish socialist party in early 1900s Russia and interwar Poland?

What brings me to both searches is a single urge: my yearning to belong, to honor, to claim and reclaim my lineages. Lineages forged by blood, by ritual, and by politics. This is why I’ve spent the past year digging up dusty books about an organization that, to my knowledge, none of my direct ancestors were a part of.

I don’t have a neat biological link to the work of this impactful Jewish socialist party, founded in Vilna (in present-day Poland) in 1897. But upon learning of its existence, and of its deep belief in a diasporic doykeit (“here-ness”), I felt an inexplicable kinship. I had to follow that feeling with the fervor of one uncovering a hidden bloodline.

Drawing inspiration from the Bund in the present day

I am not the only one, either. Amongst contemporary Jewish leftists, remembrances of the Jewish Labour Bund have uncorked a suppressed ancestry of revolutionary Ashkenazi activism. As recently noted by many Jewish artists, thinkers, journalists, and organizers, the Bund offers, across time and space, an activist ideal that feels sturdy and expansive, maybe even a usable blueprint for our current movements for liberation.

Artist and writer Molly Crabapple summarizes the value of the Bund’s still-relevant vision: “It’s basically that you can be an internationalist… That we can all be ourselves while also fighting for everyone.”

This echoes activist scholar Melanie Kaye/Kantrowitz’s invocation of the Bund’s doykeit in her seminal definition of “diaporism,” from her book “The Colors of Jews”: “Diasporism takes root in the Jewish Socialist Labor Bund’s principle of doikayt — hereness — the right to be, and to fight for justice, wherever we are…”

It may well be that the definition of “diasporism” that Kaye/Kantrowitz offered to incoming generations of Jewish activists is one primary spark in the revival of the Bund’s “here-ness” politic. It is this ethic that inspired me to reach towards the Bund, through research and poetry, towards their diasporic theory of change, from my own specific positionality, so far from the one their vision sprung from. The poems I wrote with the support of Robinovich Fellowship in Jewish Studies reflect both the fraughtness and generativeness of this reaching.

The history of the Jewish Labor Bund

The organization often shorthanded by the singular title of “the Bund” was in fact not one discrete thing, and did not exist in just one place, or even under one name. It was founded just before the turn of the century in Vilna, at that time a part of the Russian Empire, as Algemeyner Yidisher Arbayter Bund in Lite, Poyln un Rusland (General Jewish Workers’ Bund in Lithuania, Poland and Russia). This name marks the first period of the Bund and its clandestine beginnings in Czarist Russia, in which it had to fight for its Yiddish socialist ideals from the underground.

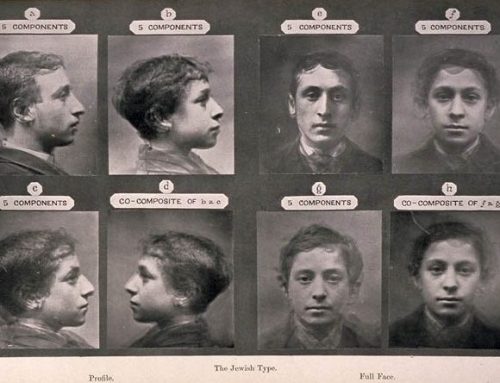

A Bundist demonstration in 1905, Dvinsk (now Daugavpils, Latvia). Via the YIVO Encyclopedia.

The Bund’s initial Russian period, from roughly 1897-1921, was characterized by its navigation of Czarist suppression and its complicated relationship with the Bolsheviks in the lead-up to the 1917 Russian Revolution. In the face of Leninism, the Bund formed a platform of social democratic Marxism, emphasizing that it could preserve Jewish identity while still working in solidarity with other Russians for proletariat revolution, and in the face of burgeoning Zionism, it offered a vision of secular Jewish cultural autonomy that did not rely on nationalism. These navigations eventually resulted in the dissolution of the Russian Bund and a shift of its center to Poland, in the wake of the Russian October Revolution of 1917 and World War I.

The Bund’s Polish interwar period, from 1919 to 1948, was a time of immense electoral movement-building, rich cultural work, and courageous self-defense patrols, all achieved despite disagreement and attacks from Polish Communists, pogroms by the antisemitic hard right, ongoing suppression by the Polish government, and the devastating Nazi occupation of Poland starting in 1939.

It is during this period that the Bund developed key auxiliary groups to serve and politicize different sectors of Polish Jewry: SKIF (Sotsyalistisher Kinder Farband – Socialist Children Union) and Zukunft (the Future), the sports federation Morgenshtern (Morning Star), the publishing house Kultur Liga, the Yiddish school network TSYSHO (Tsentrale Yidishe Shul Organizatsye – Central Yiddish School Organization), and more. Through youth work, sports, education and publishing, the Bund engaged in cultural organizing as a form of outreach and base building.

Organizing to build a socialist movement

Did these Bundist strategies actually work? As scholar Jack Jacobs writes in his introduction to “Bundist Counterculture in Interwar Poland“: “Some argue that the Bund was the most powerful political party within Polish Jewry on the eve of the Second World War.”

Members of Tsukunft, a youth movement of the Bund, putting up election posters in Baranowicze, Poland (now Baranavichy, Belarus, ca. 1930. Via the YIVO Encyclopedia.

Of course, this claim has been problematized amongst scholars of Polish Jewry. Jacobs acknowledges that the Bund never gained traction in Poland’s National Parliament, yet cites the Bund’s impressive performance in many Jewish communal and municipal elections in Warsaw and beyond. In elections for city councils and kehiles (organized Jewish community groups), the Bund increasingly outpaced its Zionist and Orthodox rivals in the latter half of the 1930s.

While there is a thorough debate surrounding possible context and significance of these victories, Jacobs’ book presents a strong survey of Bundist counterculture auxiliary groups and offers them as one possible contribution to these important electoral wins.

He concludes, “The increases in the size of the party’s children’s movement, youth movement, and physical education movement led to an increase in the total number of people who had had positive experiences in its entities and helps to explain why more people voted for Bundist candidates in city council and Jewish community council elections in the 1930s than in earlier years.”

In the face of great violence and suppression, the Bund was committed to serving the cultural needs of their community. These cultural strategies of base-building made an impact. They brought people out to the polls and into the streets. The Bund was able to shift culture towards their socialist goals through outreach and community.

While the ravages of Holocaust targeted Bundists as much as other Jewish communities of their time, to Nazi occupation in the Warsaw Ghetto and beyond.

In the aftermath of World War II, with its membership decimated, the Polish Bund attempted to re-establish itself amongst Holocaust survivors, but ultimately dissolved in 1948. While the descendants of Bundists work to keep its legacy alive today, in various locations across the globe, the Bund has never able to regain its status as a mass movement.

Rediscovering (and grieving) the Bund

Thus, I have inevitably discovered that a reaching towards the Bund is also a grieving of what it never got to be. Where might the Bund have gone with their base-building? How might have their constellation of countercultural institutions have grown?

We can never know. But we cannot forget their existence, as a highly successful, broad-based Jewish anti-Zionist Socialist movement, as a movement rooted in solidarity. We cannot let the historical narrative be that their strategy of doykeit lost, but rather that they somehow left it behind for us to find, and re-plant inside a here-ness they never could have imagined.

Shelby Handler is an M.F.A. candidate in poetry at the University of Washington, where they also graduated with honors as an undergraduate. They are at work on their first poetry collection, which “queers” accepted notions of ancestry and home through explorations of Jewish femme identity at the margins. In both form and content, these poems examine empty spaces and holes, asking what it means to belong to a mother, a family, a people, a land. The collection engages with the activist lineage of the Jewish Labour Bund, a socialist political party in the 19th and 20th centuries, and its concept of “doikayt” (“hereness” in Yiddish, referring to the strengthening of Jewish communities at a local level). She is the 2021-2022 Robinovitch Family Fellow in Jewish Studies.

Shelby Handler is an M.F.A. candidate in poetry at the University of Washington, where they also graduated with honors as an undergraduate. They are at work on their first poetry collection, which “queers” accepted notions of ancestry and home through explorations of Jewish femme identity at the margins. In both form and content, these poems examine empty spaces and holes, asking what it means to belong to a mother, a family, a people, a land. The collection engages with the activist lineage of the Jewish Labour Bund, a socialist political party in the 19th and 20th centuries, and its concept of “doikayt” (“hereness” in Yiddish, referring to the strengthening of Jewish communities at a local level). She is the 2021-2022 Robinovitch Family Fellow in Jewish Studies.