Mural depicting the movement of Torah scrolls following the expulsion from Spain. From Wilshire Boulevard Temple, Los Angeles.

By Vivian Mills

One of the questions that I get asked repeatedly when people learn about my field of study – the literature and culture of Sephardic Jews during the Middle Ages – is, “Why are you interested in this subject?”

The answer is simple: The Middle Ages were more like our world today than we are inclined to think. The same philosophical questions we have today about our purpose and place in the universe were being asked a thousand years ago; and although the political organization was different during those times, the political issues that arose are the same as the ones we are confronted with today.

This leads me to the issue I want to tackle: what happens to an ethnic and religious minority when a political majority tries to consolidate its power. The dynamics of power that held true in the Middle Ages hold true now.

The Synagogue of El Tránsito in Toledo, built by Samuel ha-Levi circa 1356

From circa 400 CE to 1492 CE, Jews in Iberia (present-day Spain) were a religious minority with no political or martial power that lived under the auspices of the reigning monarch. Jews were granted special dispensation to live among the ruling political majority by writs or special licenses, according to their status as property of the king (servi camarae) in the Christian kingdoms, and as protected minorities or dhimmis in the Islamic Andalusian Caliphate and in the Taifa principalities that followed it.

As Jews were dependent on the strength of the reigning monarch for their continued subsistence, it is not surprising that the lives of the Sephardic Jews in the Iberian Peninsula were tied to the political tides that battered the region during the Middle Ages. The conversion of the Visigoths from Arianism to Catholicism in 589 CE was the first instance of a political majority’s consolidation of power that had a profoundly negative effect on the lives of Iberian Jews.

Under Gothic rule

After the fall of the Roman Empire in the fourth century, the Visigoths invaded Iberia, and they found a sizable Jewish population there. By the sixth century, instability and internal power struggles beset the region. By this time, the Gothic language was extinct and the division between the native Hispano-Romans and the conquering Goths was negligible.

Attempting to unify a kingdom burdened by internal struggles, the Visigoth kings abolished the laws that treated the Hispano-Romans and the Goths differently and converted to Catholicism, associating themselves with the growing power of the Church.

1888 painting by Antonio Muñoz Degrain depicting the conversion of the Visigoth king Reccared I.

Following this conversion, the Visigoth rulers implemented a series of harsh laws that targeted the Jewish population, forcing conversions, proscribing circumcision, and declaring that conversion to Judaism was punishable by death. These laws eventually led to the first edict of expulsion of the Jews of the Iberian Peninsula by Sisebut in 613 CE. Much of the Jewish population converted to Christianity or fled toward the territories in Northern Africa.

Less than a hundred years later, the Visigoth kingdom came to its end with the Islamic Umayyad invasion of the Iberian Peninsula, which left only a few enclaves of Christian kingdoms in the north. Following the Visigoths’ fall from power, many of the Jewish people that had converted to Christianity under their rule returned to Judaism.

Under Islamic rule

The Umayyad Caliphate lasted a century and was known for its relatively tolerant attitude toward other religions and ethnicities under the dhimma, or protected minority status for followers of monotheistic religions like Jews and Christians. As a result, the Jewish population of Al-Andalus – the Islamic name of Iberia – flourished.

When the Umayyad Caliphate of Cordoba disintegrated in 1031 CE, the Al-Andalusian principalities or taifas (Arabic tawā’if, parties) that remained were embroiled in political strife, often warring against each other. They were also involved in complicated power struggles and alliances with the Christian kingdoms in the north.

The Al-Andalusian princes invited the Almoravids and later the Almohads from North Africa to aid in their struggle against the increasing power of the northern kingdoms. These groups practiced a type of Islam that was much stricter than that of the Andalusians. As their power gradually disintegrated, the Almoravids tried to unify the population under the banner of Islam. By 1140 CE, edicts were issued that forced the Jewish minorities under Andalusian rule to convert under penalty of exile, and strict observance of Islam was required. Many Jews fled toward the newly conquered Christian territories in the north.

Under Christian rule

Alfonso X, also known as the Wise, and his Jewish courtiers

During the following three centuries, the Jewish population of the northern Iberian Peninsula had what could be described as a relatively prosperous period under the protection of the Christian kings, becoming involved in regional commerce, agriculture, and government administration.

This would change dramatically by the end of the fourteenth century, when political strife brought about by competing dynasties, economic hardships, and anti-Semitic campaigns in the rest of Europe led to a virulent campaign against the Jewish population of Castile. Castilian Jews were accused of exploiting Christians through their positions as tax collectors and administrators.

The aljamas (Jewish settlements) of Castile suffered a series of terrible pogroms, the product of several campaigns of defamation and anti-Jewish propaganda, like the one led by the infamous Ferrán Martínez that resulted in the Massacre of Seville of 1391 CE. These events served as a foreshadowing of what was to come just a few decades later.

Following their marriage in 1469, Isabella of Castile (1451-1504 CE) and Ferdinand II of Aragon (1452-1516 CE) decided to bring their unified kingdoms and newly conquered territories under one religion and one language in order to strengthen their position.

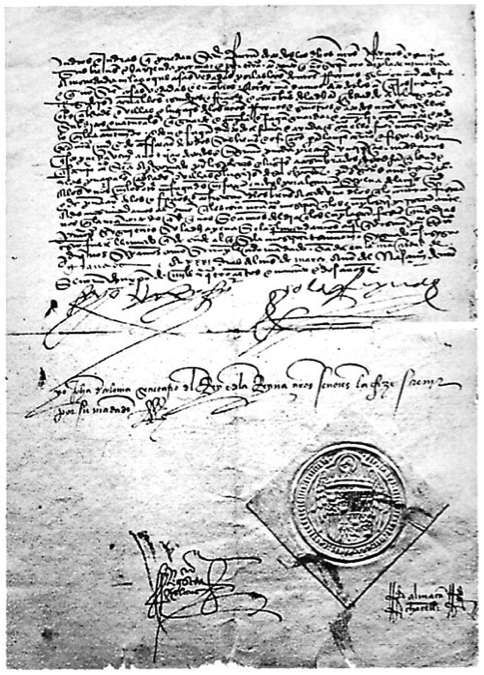

A copy of the Edict of Expulsion or Alhambra Decree issued the 31st of March 1492

Isabella was involved in a dynastic war with Joanna, Queen consort of Portugal (1462-1530 CE), the daughter of her half-brother, King Henry IV (1454-1474 CE). Joanna was rumored to be the daughter of Henry’s favorite, Beltran de la Cueva, and was known as “Juana la Beltraneja.” After the death of Henry IV in 1474 CE, Isabella and Joanna went to war for the right to rule Castile. Two years later, Isabella and her husband Ferdinand emerged victorious and were known from then on as the “Catholic Monarchs,” the rulers of the kingdoms of Castile and Aragon.

Given the rising hostility against Jews in Castile and the rest of Europe and their precarious position as new monarchs, Isabella and Ferdinand felt pressure to take decisive action against the Jewish population of Iberia, having previously enacted a series of policies that sought to reduce Jewish influence in society. The Catholic monarchs issued the final edict expelling the Jews from the territories in the Iberian Peninsula on the 31st of March 1492, almost a whole millennium after the first edict by the Visigoths.

The same year, the keys of the last remaining Islamic Al-Andalusian stronghold were turned over to Isabella and Ferdinand; a few decades later, the mudejares – Islamic people that stayed in Castile after the conquest of Granada – were also expelled from Spain. With the expulsion of the Jews and Muslims went over two thousand years of knowledge, love for the land, and tradition, and the newly minted kingdom of Spain was much poorer for it.

The cost of exclusion

The purpose of this bird’s eye view of almost a thousand years of history is to highlight certain patterns that occur when a political majority tries to shore up its power against changes caused by political or social forces. These majority efforts to consolidate power often have consequences for minorities, who suffer forced assimilation or exile. In these cases, it seems that majorities “win,” while minorities lose. But do majorities actually “win”?

After a hundred years of prosperity – thanks in part to the riches of the Americas – Spain went through a sharp decline in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. There were many contributing factors for this, among them failed economic and political policies, but an important factor that is often underappreciated is the incredible intellectual and economic power that went away with the expelled minorities, who were excluded from the definition of “Spaniard.”

The push towards persecution in Spain did not end with the expulsion of Jewish and Islamic people. Spain turned on its own citizens and established the Inquisition and a system of castes – old and new Christians – that furthered divided its population.

How different are these issues from those we see highlighted in the everyday news of our own times? Today we see powerful political and economic majorities trying to strengthen their weakening influence by ostracizing those with less power here in the United States, as well as in the rest of the world. Institutionalized racism, forced assimilation and exile are weapons that are also used today against those with less political power.

Let us not forget, then, that by casting our eyes towards the past and examining the consequences of excluding minorities, we have the opportunity to learn how to better deal with our present. Perhaps we can even learn how to build a better future for all.

Vivian Mills is a second-year PhD student in Spanish and Portuguese Studies at the University of Washington. She was born in Ecuador and moved to the United States with her family at the age of sixteen. She received a BA in Business Economics and an MA in Spanish from the University of South Florida. Her research focuses on identity and the building of textual authority in the literary works of Jewish, Converso and Morisco writers of late medieval and early-modern Iberia. Her latest research focuses on the works of Shem Tov of Carrion, a medieval poet and rabbi. When not reading poetry, you can find Vivian at work in her garden or spending time with her family.

Vivian Mills is a second-year PhD student in Spanish and Portuguese Studies at the University of Washington. She was born in Ecuador and moved to the United States with her family at the age of sixteen. She received a BA in Business Economics and an MA in Spanish from the University of South Florida. Her research focuses on identity and the building of textual authority in the literary works of Jewish, Converso and Morisco writers of late medieval and early-modern Iberia. Her latest research focuses on the works of Shem Tov of Carrion, a medieval poet and rabbi. When not reading poetry, you can find Vivian at work in her garden or spending time with her family.

Leave A Comment