The Ahrida Synagogue in Istanbul, Turkey. The oldest synagogue in Istanbul, dating back to the 15th century, with a boat-shaped central platform (bima).

By Elyakim Suissa

“Woe to Yosef! Woe to Yosef!” cried the Muslim customer to one Rabbi Avraham Albalidah in the rabbi’s shop in Gallipoli (Gelibolu in present-day Turkey; then part of the Ottoman Empire) in the mid-sixteenth century. “I saw him killed and discarded under the bridge… and when I returned to that place again, I looked for him but did not find him.”

There had indeed been a missing Yosef Shaltiel who resided in Gallipoli. There were also rumors that Yosef had been killed. However, without concrete proof of a body, practical issues would arise. Yosef’s widow Pasana would be forbidden from marrying another man according to the precepts of Jewish law. If she remained a widow, Pasana would likely live a life of poverty and low social status, not to mention loneliness and solitude.

Upon hearing this information from his customer, Rabbi Albalidah recounted this story to the local Jewish beit din, the court in which all matters of Jewish law were decided.

The beit din asked Albalidah a series of questions concerning Yosef’s identity: Could Albalidah be sure that this Muslim customer knew Yosef Shaltiel and was able to recognize his body? Where was the bridge located? On the day that the Muslim had entered the rabbi’s shop, could it have been that another Yosef was also missing?

Albalidah answered: Not only did the Muslim surely know this man, but every resident of this area of Gallipoli knew who Yosef Shaltiel was. The bridge was close to half a day’s march from Gallipoli. There was not another Yosef missing from Gallipoli besides this Yosef.

We are told that Albalidah’s claim was bolstered by a Jewish merchant present in the courtroom, who testified that Yosef Shaltiel alone, and no other Yosef, was missing from Gallipoli.

This description appears in a collection of texts known in Hebrew as she’elot u’tshuvot (“questions and answers”), a genre that arose in the ninth century and produces new writings through the present day. This genre is part of the body of practical law in Judaism that applies to everyday life.

Responsa, questions and answers, she’elot u’tshuvot

Judaism, in addition to being a religion, incorporates a complex system of law that is intended to encompass all aspects of life, the mundane as well as the spiritual. The genre of she’elot u’tshuvot, also known as responsa, comprise questions on specific scenarios submitted to renowned rabbis in urban centers who possessed the training necessary to issue rulings on such precise issues.

These writings, especially during the beginning of their proliferation in medieval Europe (around the ninth to twelfth centuries), were often implicitly used to strengthen communication and authority between rabbis of different geographical communities across Europe and the areas conquered by the Ottoman Empire.

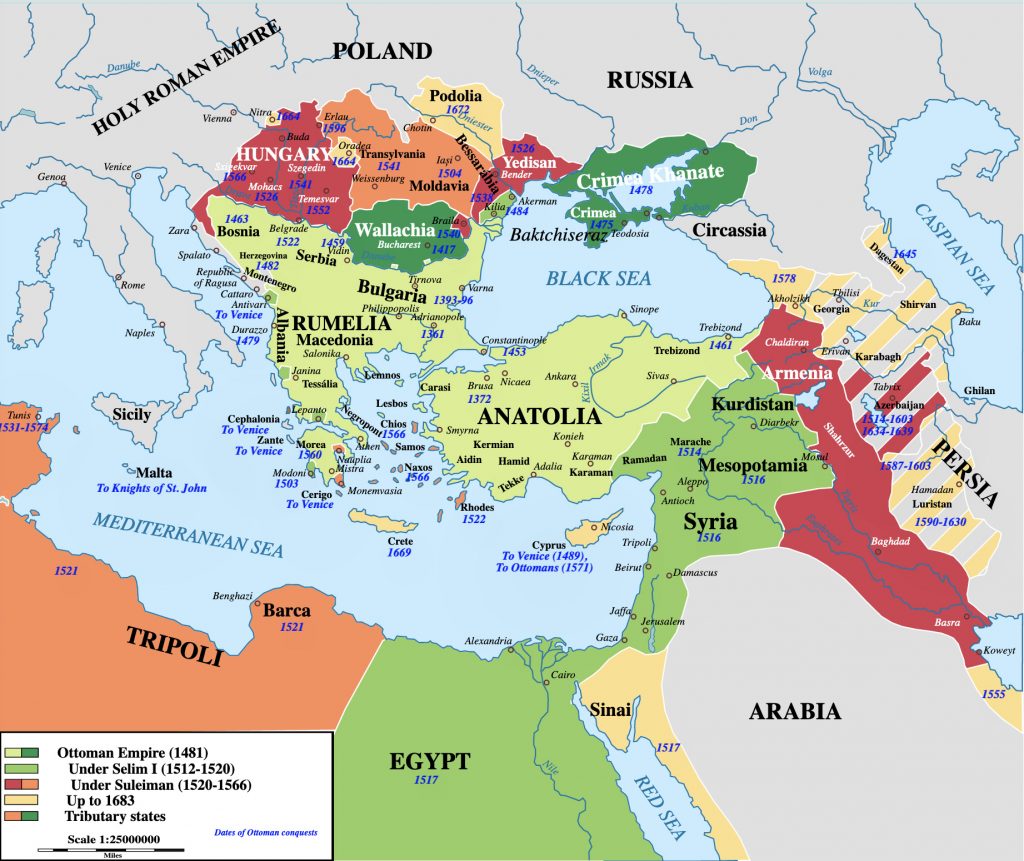

The Ottoman Empire, 1481-1683. Via Wikimedia Commons.

The Ottoman Empire, at its widest territorial expansion, ruled the modern-day Middle East and north Africa, and even spread to eastern and central Europe. In the sixteenth century, when this case was recorded, the majority of Jews in the Ottoman Empire had recently arrived from the Spanish exile of Jews in 1492. While the primary spoken language of most Jews in the Ottoman Empire was Ladino (Judeo-Spanish), responsa were almost solely authored in Hebrew, the intellectual and religious language of Judaism from biblical times until the modern day.

These texts, such as the one featuring the anecdote described above, are uniquely situated to give us nuanced glimpses into the workings of Ottoman Jewish life, especially concerning the realities and tensions of coexistence with Ottoman Muslims.

Legal considerations: Rabbi Yosef ben Lev’s ruling

The responsum quoted above was answered by Rabbi Yosef ben Lev (circa 1505-1580), known by his Hebrew acronym, the Maharibal. The Maharibal, originally born in Yugoslavia, had settled in Istanbul’s Sephardic Jewish community — composed of Jews who had moved from the Iberian Perninsula — after having built up his reputation in Salonika (also known as Thessaloniki, in present-day Greece) as an adjudicator for about fifteen years prior.

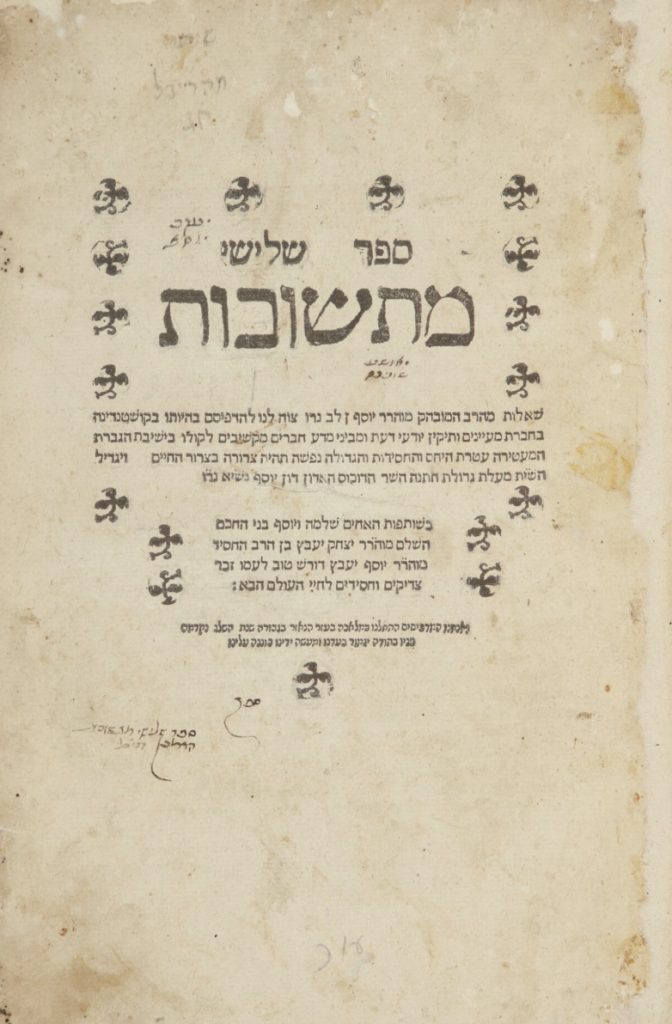

Title page from a first edition collection of Rabbi Yosef ben Lev’s responsa, circa 1557. Via Sotheby’s.

At the end of his lengthy response to the difficult issue of Yosef Shaltiel and Pasana, Rabbi ben Lev concludes that Pasana is unable to remarry, as there is not enough proof to confirm Yosef’s death. The corpse allegedly witnessed by the rabbi’s Muslim customer cannot be definitively identified as Yosef Shaltiel according to the criteria set forth by Jewish law.

Rabbi ben Lev stipulates that for this discussion, “One must study and research and know, that when there is a conflict between the poskim [rabbis who are authorized to issue rulings on Jewish law] in a matter similar to the one of our discussion, whether we should proceed according to the lenient opinion due to concern for the woman in a chained marriage [a marriage a woman cannot legally end under Jewish law, even when the relationship is practically over], or whether we should proceed according to stringency.”

The rabbi raises three main “doubts” related to this case that prevent him from ruling in Pasana’s favor. These doubts are: the distance in time between the man’s death and the Muslim’s informal testimony; the precedent that a firsthand viewing is required in order to identify the dead; and the fact that the Muslim, in his informal testimony, mentioned neither the name of the dead man’s father nor the name of his city, pieces of information that are part of Jewish protocol in confirming the dead.

Real-life details from this case

What questions and answers of our own may we glean from this story? Given the level of detail and the rare mentions of actual names (the vast majority of responsa follow an anonymized naming pattern), this responsum is a perfect example of a text that allows historians to read between the lines to identify social patterns and perhaps even tensions.

For example, we might wonder what type of shop Rabbi Albalidah operated, especially since it was frequented by at least one Muslim customer. We may also note the cautious level of detail used by the author in specifying the religious identities of all actors in the scenario (note that another Jewish merchant is said to be present in the courtroom). Despite Rabbi ben Lev’s absence of explicit concern as to the witness’s Muslim identity, the question is clearly written to include this detail in case it might be problematic.

This text and others like it also show us the nuances of religious law, especially as Rabbi ben Lev bases his response on the responses of predecessors who dealt with similar issues, participating in a chain of tradition that had practical consequences for its non-rabbinic adherents.

Islamic responsa from Istanbul in the same era

We can find similar nuances in the Islamic tradition of religious legal rulings that came out of Istanbul in the same era. For example, in one question sent to Ebüʾs-suʿūd (1490-1574), the chief Islamic jurist and a contemporary of Yosef ben Lev, it is asked whether a non-Muslim’s testimony about another non-Muslim’s right of inheritance is considered reliable.

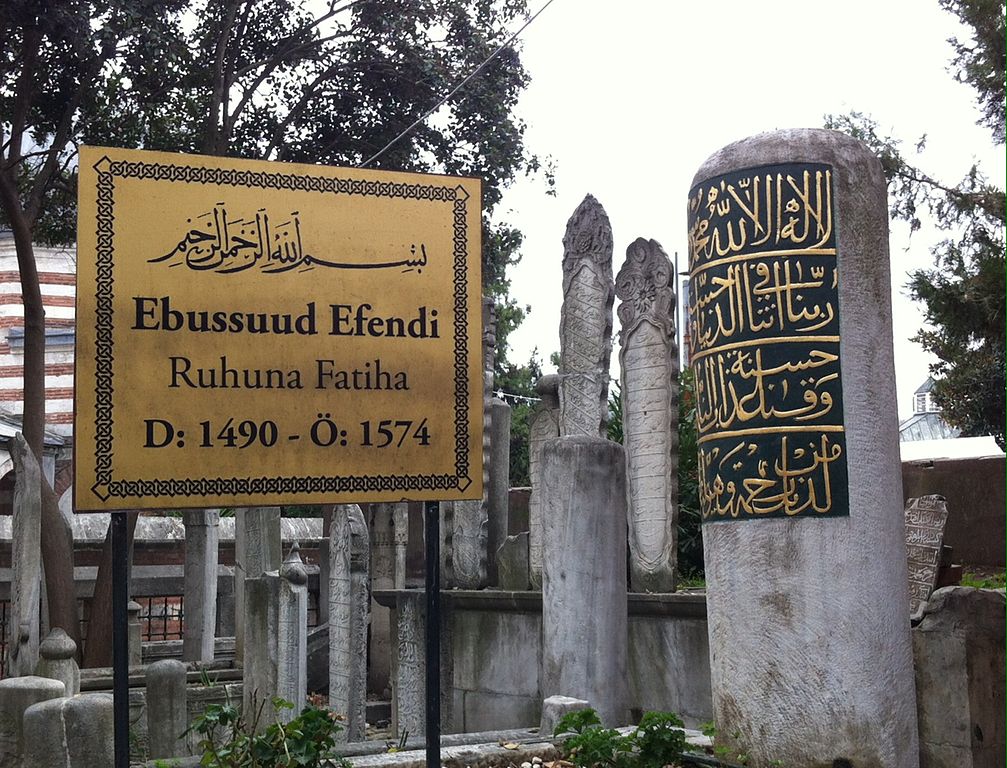

Tombstone of Ebüʾs-suʿūd, chief Islamic jurist of Istanbul in the mid-16th century. Photo by Nadiya, via Wikimedia Commons.

The concern is based on a document (dated 1543) about merchants from Dubrovnik — a city in present-day Croatia, then a tributary state of the Ottoman Empire — that contains the statement, “it must be investigated whether there is a Muslim witness.” Ebüʾs-suʿūd maintained that this is a custom that is “peculiar to the people of Dubrovnik.”

Here, we are given insight into the nuances of tradition. Although a statement issued by Ebüʾs-suʿūd, the highest official authority of Islamic law in the Ottoman Empire, would be considered binding, he implicitly maintained the validity of a different custom as well – the local precedent, specific to Dubrovnik, that a Muslim witness must be seen.

The historical value of responsa: Insights into the past

Religion in the Ottoman Empire was all-encompassing. The voluminous collections of responsa issued by Yosef ben Lev, Ebüʾs-suʿūd, and countless other renowned Jewish and Islamic jurists were designed to apply to all aspects of life, for each member of the Empire’s social class.

However, the nature of these rulings were such that the power of their authors to enforce their own rulings mainly stemmed from their reputations and social pressure.

As the cases described illustrate, these responsa offer insights not only into the legal thinking of the time, but also the culture and society that surrounded the adjudicators of religious traditions. With this in mind, historians can explore more of these texts to investigate the hierarchical dynamics between their authors, the populations whose lives they affected, and the societies that enveloped them.

These texts are not only relevant for modern-day rabbis and imams. They are indispensable historical documents that can help us make sense of distant worldviews.

Elyakim Suissa received his Master of Arts from the Department of Middle Eastern Languages and Cultures in 2024. His research, focusing on Jewish rabbinic law, literature, and community in sixteenth-century Istanbul, has brought him to Israel and Turkey, where he has enrolled in several language and research programs. His recent M.A. thesis uses Hebrew-language responsa and Ottoman Turkish fetvas to analyze themes of communal cohesion and religious space that jointly affected both Judaism and Islam. He looks forward to continuing this research as a doctoral student of the University of Pennsylvania.

Elyakim Suissa received his Master of Arts from the Department of Middle Eastern Languages and Cultures in 2024. His research, focusing on Jewish rabbinic law, literature, and community in sixteenth-century Istanbul, has brought him to Israel and Turkey, where he has enrolled in several language and research programs. His recent M.A. thesis uses Hebrew-language responsa and Ottoman Turkish fetvas to analyze themes of communal cohesion and religious space that jointly affected both Judaism and Islam. He looks forward to continuing this research as a doctoral student of the University of Pennsylvania.