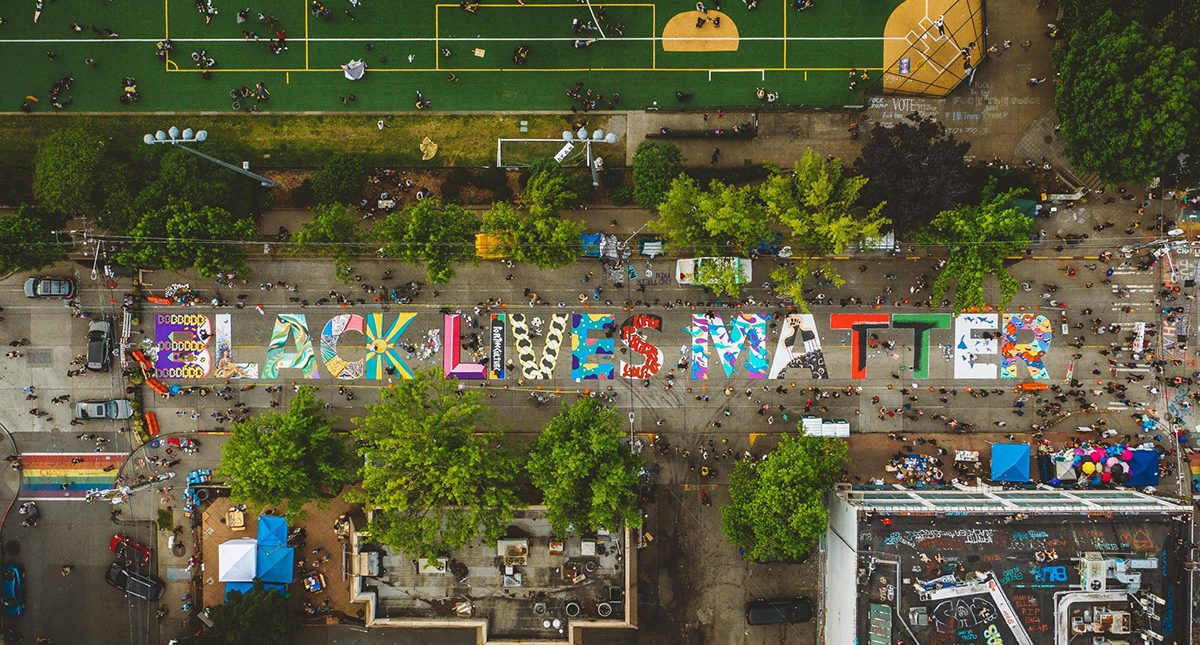

Photo of Capitol Hill, Seattle, in June 2020 by Kyle Kotajarvi.

Over the last few months, Stroum Center faculty have been discussing the relationship between their work as scholars and the national call to address the systemic roots of racial inequalities in the U.S.

Below, faculty members share their reflections on what Black Lives Matter means to them from their vantage points as scholars, teachers, and individuals.

Mika Ahuvia, Assistant Professor, Jewish Studies, Comparative Religion, International Studies

When I hear “Black Lives Matter,” I think of the three women who coined the phrase as an affirmation of Black life and dignity in a society that has, unfortunately, taught black folks that their lives don’t matter. I think of the phrase Am Yisroel Chai (“the people of Israel live/endure”) and how this affirmation also arose from fraught historical circumstances to affirm Jewish survival and dignity. I hear Black Lives Matter as a call and challenge to be a better teacher, colleague, friend, and ally to Jews of color and all Black, Indigenous, and other People of Color. I hear it as a call to be a better citizen of my community (whether that’s UW, Seattle, the U.S., or the world).

Nicolaas P. Barr, Lecturer, Comparative History of Ideas

When I hear “Black Lives Matter,” I hear the demand for justice that has been promised but never fulfilled. I see Black collective strength and leadership, and a vision that refuses complacency. I hear an echo of James Baldwin’s open letter to Angela Davis in 1970:

We must do what we can do, and fortify and save each other — we are not drowning in an apathetic self-contempt, we do feel ourselves sufficiently worthwhile to contend even with inexorable forces in order to change our fate and the fate of our children and the condition of the world! We know that a man is not a thing and is not to be placed at the mercy of things.

Smadar Ben-Natan, Benaroya Postdoctoral Fellow in Israel Studies

For me, “Black Lives Matter” signifies struggle and inspiration: The ongoing struggle of Black and all people of color in the US for life with dignity, and the leadership of the black community in the quest for justice and human rights. As a human rights scholar and lawyer, I rely on the teaching of Angela Davis: “Freedom is a constant struggle.” From the abolition of slavery to the civil rights movement, anti-colonial movements, the defeat of South African apartheid, and the Black Lives Matter movement, Black people have been forced to fight for the most fundamental right to be considered human. They have made enormous sacrifices and their struggles have become an inspiration to so many. The Jewish people that I am part of have also endured racism, persecution and genocide, exemplifying resistance, perseverance, and leadership in the modern human rights movement. These hardships and struggles should teach us that they should not be fought in isolation. Black Lives Matter, for me, is a call for solidarity.

Daniel Bessner, Associate Professor, International Studies

When I hear Black Lives Matter, I hear a call to solidarity that spans races and genders, a call for equity in a system that rewards, protects, and defends the few at the expense of the many. I hear a critique of U.S. imperialism and the damage it has wrought at home and abroad. And I also think of the many Jewish Studies scholars who have devoted their lives to racial justice and equity, and hope that my own generation of Jewish Studies scholars will take the best of their forerunners and expand their vision to include people in the United States and abroad.”

Richard Block, Associate Professor, Germanics

When I hear “Black Lives Matter,” I am reminded of how the term “chosen people” was explained to me as a young child. Given our history of oppression, we as Jews were chosen to always stand and fight with the oppressed, and to recognize their plight as our own. Clear then as now is that the work is never finished, but always only beginning. And to save one black life is to save a world, and there are so many worlds to save.

Susan Glenn, Professor, History & Jewish Studies

When I hear the cry “Black Lives Matter,” I think of “We Charge Genocide: The Historic Petition to the United Nations for Relief from a Crime of the United States Against the Negro People.” Presented to the U.N. in 1951, this petition sought to demonstrate that the government of the U.S. was in violation of the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of Genocide which had been adopted by the U.N. in 1948 in the aftermath of the Holocaust. “We Charge Genocide” documented 152 recent killings (largely by the police), and 344 other unpunished crimes of violence against African Americans, and other human rights abuses by the United States against its own citizens from 1945-1951. This represented only a small sample, as most crimes against Black people went unrecorded. Learn more about this history here.

Brendan Goldman, Hazel D. Cole Postdoctoral Fellow in Jewish Studies

When I hear “Black Lives Matter,” I am struck that a self-evident statement of humanistic values remains an elusive ideal for our nation. I am reminded that the advancement of science and industry over the past two centuries is inseparable from contemporaneous acts of enslavement, colonialism and genocide. I am forced to embrace the conviction that the arc of history bends towards nothing without our will to shape it.

Liora Halperin, Associate Professor, Jewish Studies & History

When I hear Black Lives Matter, I hear a demand to study the history of our country and internalize how uniquely ugly and unjust that history has so often been for black Americans. I hear an imperative to allow myself to be uncomfortable, alarmed, and activated by the fact that injustice not only structures this country’s past but also its present. I hear a call to engage critically in conversations about what it would take to remedy those injustices. As a Jewish Studies scholar, I hear a demand to take seriously the experiences and history of Black Jews and Jews of Color. I draw insights from the study of the Jewish past about the causes and consequences of systemic injustice against a group of people, including injustice in which Jews were and are implicated.

Laurie Marhoefer, Associate Professor, Department of History

When I hear “Black Lives Matter,” I hear a statement of fact that should not need to be said, and I remember the urgent need to fight against violent racism in the United States, a need that moves me not only as a white person who lives in this country and needs to fight racism, too, but as a historian of Nazi Germany, who knows all too well the unspeakable cost of racism.

Devin E. Naar, Associate Professor, History & International Studies

“Black Lives Matter” brings to mind a refran, or proverb, in the Sephardic Jewish language, Ladino: “Si te ambezas la ley de un ladron, el arovar te parese una mitzva.” “If you learn the law from a thief, stealing seems like a mitzvah (an obligation or good deed).” It may be difficult to acknowledge, but the laws of our country were established by thieves on land stolen from Indigenous people who built up our society through labor stolen from people kidnapped from Africa and enslaved across the generations for a quarter of a millennium. Black people (and Indigenous people) were intentionally and violently excluded from the founders’ call of “We the people.” We are the heirs of the distorted rules of engagement that set this country in motion. It is our responsibility, as scholars and as members of our society, to unlearn and transform those very rules set out by the founders, so that Black lives will matter, so that we may pursue the mitzvah of justice once and for all.

Scott Noegel, Professor, Near Eastern Languages & Civilization

When I think of “Black Lives Matter” I feel deep sadness at the historically epic failure of so many human beings to recognize that we are one people. I am bewildered by, and feel shame for those whose hatred is so deep over such shallow differences. Yet, I also feel buoyed by the hope that the cries for equality will once and for all drown out the cowardly voices of racism. When I think of “Black Lives Matter” I think of imminent, positive change.

Noam Pianko, Professor, International Studies

When I hear “Black Lives Matters,” I am reminded that any discussion about group identity in the United States must recognize the centrality of race and racism in this country. American Jewish historians studying the process of Jewish integration and Americanization have certainly underscored the ways in which the United States has used racial ideas to limit Jewish immigration and to exclude Jews from full social, legal, and political participation. However, we have spent far less time grappling with the ways that anti-Black racism created opportunities for Jews complicit in these hierarchical systems to achieve an exceptional level of acceptance as a white religious minority community. Black Lives Matter challenges me to underscore this uncomfortable reality in my teaching and scholarship.

Sasha Senderovich, Assistant Professor, Slavic Languages and Literatures

When I hear “Black Lives Matter,” I hear a call to re-examine my own life narrative in relationship to the mythology of the United States that I’ve had access to as an immigrant to this country. The myth of “pulling oneself up by your own bootstraps” is strong in the Russian Jewish immigrant community, mainly comprised of Ashkenazi Jews who are white, a group to which I belong. It has been important for me to begin to learn how many Jews who faced personal and systemic discrimination in the Soviet Union leaned heavily into the American myth of endless possibilities, as I did. Focused on “making it” in our new country — which many of us did in one way or another — we sometimes account for our success through personal ambition alone. The BLM call for racial justice and for a reckoning with the past has helped me understand and think more deeply about how most Soviet Jews benefited from being read as white after entering the U.S. starting in the 1970s. For me, a one-time immigrant who is a white person in the system of U.S. racial hierarchies, “Black Lives Matter” has meant, for now, reading works of literature and scholarship that have helped me come to painful and necessary understandings of how I have become — and how I am — an American.

Hamza Zafer, Associate Professor, Near Eastern Languages and Civilization

When I hear “Black Lives Matter,” I hear a call to something beyond the individual. I think collective voices, collective responsibilities, and collective responses. I hear the slogan of a movement that is building solidarity across socio-economic, racial, and religious differences in our society. I hear an affirmation of common grounds.

Leave A Comment