Special thanks to the Mitchell F. and Sophie Wise Ehrlich Student Support Fund in Jewish Studies and to Honorary Board member Arlene Ehrlich for establishing this fund in memory of her parents.

By Moshé Elias

Immediately after graduating from the University of Washington in June 2018, I enrolled in an intensive Yiddish-learning program at the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research. Who wants to go to summer school right after graduating from college? One who loves learning, that’s who. That’s me!

I’m not your average Ashkenazi boy learning Yiddish to reclaim a part of a long-lost, vibrant Jewish culture that existed in Central and Eastern Europe for generations. Surprising as it may sound, I undertook the Yiddish immersion experience as an Iraqi Arab who comes from a Muslim-Jewish background.

As a native speaker of Arabic and someone who grew up practicing Judeo-Arabic, I had the opportunity in college to explore the complexities and beauty of different Jewish communities. I landed on Yiddish after an academic journey in Jewish studies (and political science) at the University of Washington.

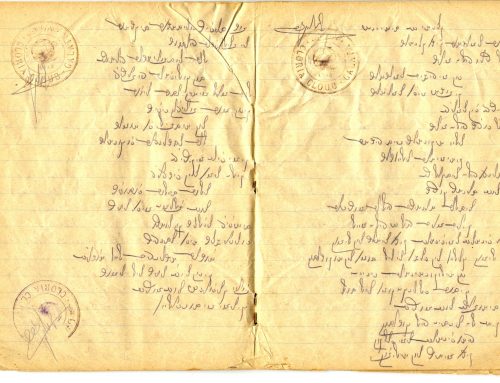

Moshé Elias with YIVO classmates at an event

In the Uriel Weinreich Zummer Program, I studied Yiddish language, literature, and culture; an eye-opening experience. Being a YIVO student allowed me to observe and participate in various entertaining events such as concerts, plays, and musicals, in addition to Shabbat dinners, potlucks, movie nights, and more; all of which were related to Yiddish language and culture. These occasions played a significant role in my immersion in Yiddishkeit (the “Yiddish” or “Jewish” way of life), linguistically, culturally, socially, and spiritually — all while cultivating a deeper understanding of the rich history of Eastern & Central European Jewry.

I encourage you to take the opportunity, if at all possible, to learn Yiddish; preferably in a place where you can be surrounded by archives, like I was when I studied at YIVO.

I will share two reasons I believe Yiddish language and culture should be studied. First, language as a key. Yiddish provides access to many important documents of Jewish history — in particular the magnificent, complex, and dramatic experiences of Ashkenazi Jews before, during, and after the Holocaust — and literature.

Second, language as a bridge. Surprisingly, speakers who come from very distant regions share idioms and other cultural similarities. Though Yiddish and Judeo-Arabic/Arabic don’t have many linguistic similarities, they have cultural connections, in idiomatic expressions, sayings, and proverbs used by ordinary speakers.

Language as a key

My appreciation for learning and studying Yiddish stems from my deep interest in its rich literature. For intellectuals who were part of the 19th-century Yiddishist movement, Yiddish was the main spoken and written language used in books and newspapers, and on the stage in Yiddish theater.

Celia Dropkin, from the Jewish Women’s Archive

I was quite amazed in observing the social and political progressiveness of Yiddish-speaking intellectuals, both before and after the Holocaust. In her poems, Celia Dropkin, a prominent early 20-century Yiddishist, presents herself as a feminist, non-conformist writer. “Mein Mame” (“My Mother”) is one of Dropkin’s most famous poems, in which she describes her widowed mother as a hero. Losing her father as a child, when her mother was only 22, Dropkin emphasizes her mother’s responsibility in taking good care of herself and her younger sister, whom she raised and educated as a single mother between the late 1800s and early 1900s.

Yiddish theater often brings to attention problems and issues affecting society and addresses them in a progressive, sometimes sarcastic, sometimes serious tone. One example is “Fiddler Oyfen Dakh” (“Fiddler on the Roof”), a famous play that depicts life in a Russian shtetl (a small Jewish town).

“Fiddler Oyfen Dakh” tells the story of a milkman called Tevye who aims to marry off his five young daughters through a matchmaker, the traditional way of getting married. Refusing to have their marriage arranged by someone else, Tevye’s oldest three girls (Tzeitel, Hodel, and Chava) stand for themselves and depart from the norm. Tzeitel marries her beloved poor tailor; Hodel marries a revolutionary student with whom she moves to Siberia and Chava ends up marrying a non-Jew. In demanding their right to choose their life-partners, Tevye’s daughters resist classism, ethnocentrism, and patriarchy.

Based on the works of Yiddish writer Sholem Aleichem, “Fiddler Oyfen Dakh” is a masterpiece where prominent social issues are addressed on the stage of the Yiddish theater.

Yiddish literature is a treasure, and Yiddish is the key that unlocks it.

Language as a bridge

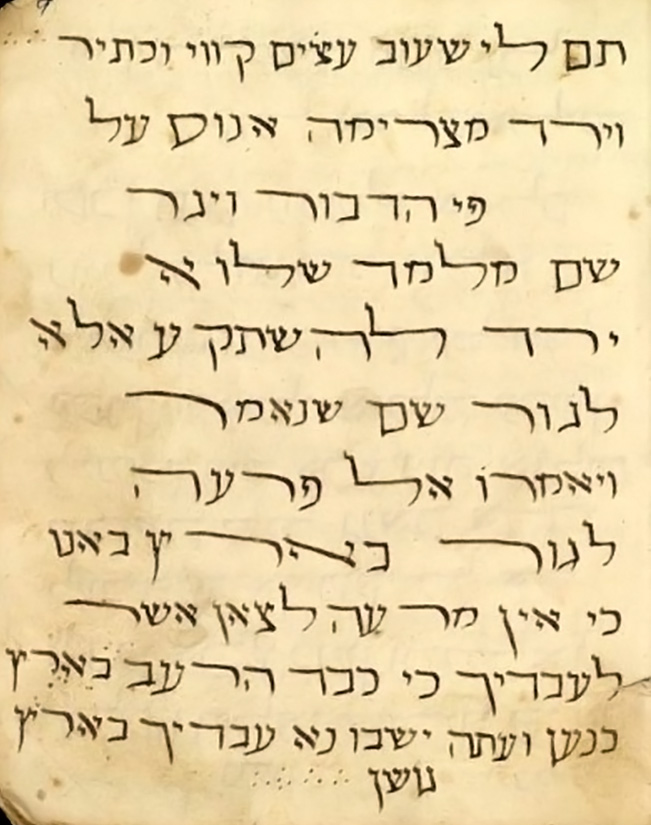

Handwriting in Judeo-Arabic

It may seem like there could be no two further languages than German and Arabic, and yet there exists a complex, rich, and often unseen connection between the two. Yiddish — a Hebrew-influenced sub-dialect of German — and Judeo-Arabic — a Hebrew-influenced sub-dialect of various Arabic dialects — are both historic languages written in Hebrew script by diaspora communities.

While German and Arabic are not related, linguistically speaking, these two sub-dialects are very much culturally connected. These two Judaic languages are a testament to the cultural connection between both the Eastern/Central European and North African/Middle Eastern Jewish communities.

Judeo-Arabic is categorized as a Semitic language because it is derived from Arabic, a Semitic language; additionally, it contains influences from other Semitic languages including Hebrew and Aramaic, while Yiddish is categorized as a Germanic language (though it does contain some Aramaic influences as well).

Although Yiddish and Judeo-Arabic neither sound similar nor share many words in common, there do exist idiomatic expressions, proverbs, and phrases that link the languages together.

The tables below offer a collection of words and sayings that Yiddish and Arabic share.

| Word/Phrase | Yiddish | Transliteration | Arabic | Transliteration |

| Blessing | ברכה | Brokha | بركة | Baraka |

| Dream | כאָלעם | Kholem | حلم | Helem |

| Peace | שלום | Sholem | سلام | Selam |

| Sugar | צוקער | Tsukar/Truker | سكر | Sukkar/Suker |

| Lemon (one piece) | לימענע | Limene | ليمونة | Limone |

| Female Sultan | סולטאַנאַ/סולטאַנע | Sültàna/Sültànè | سلطانة | Sültàna/Sültàne |

| Hello/Peace upon you (Greeting) | שלום עליכם | Sholem Aleykhem | سلام عليكم | Salamu Aleykum |

| Response to the above | עליכם-שלום | Aleykhem Sholem | عليكم السلام | Aleykum Selam |

| Some proverbs commonly used in both Yiddish & Arabic (depending on the dialect) |

| In one ear, and out the other |

| Walls have ears, and streets have eyes |

| Give the bread to its baker |

| Walk for a month, but don’t cross a river for a shortcut |

| If one is ugly, he/she blames it on the mirror |

| It’s hard to steal from a thief |

| Don’t beg for a sandal from the bare-footed |

As one whose mother tongue is Arabic, I found it fascinating that there was a cultural connection between two languages that have vastly different origins and influences and are spoken in geographically isolated regions.

Language is a bridge; it shows that one may not need to sound similar to members of another group in order to find cultural commonalities with them. In engaging in cultural exchanges, there are many surprising lessons to learn.

Choosing to study Yiddish

What I would like to share with you is a message of hope and support. As individuals, our race, belief, national origin, etc., should not dictate what we want to study or where and what we want to learn. In fact, some of my peers at the YIVO were not Jewish and were learning Yiddish just for research purposes.

Regardless of my own connection to Judaism, I chose to include Jewish studies as part of my educational journey at the UW as an individual; someone of varying interests and motivations, rather than someone who is restricted — and actually limited — by labels. This is especially applicable to those who come from complex identities, including myself, where the question of which part of that identity to prioritize can always be debated.

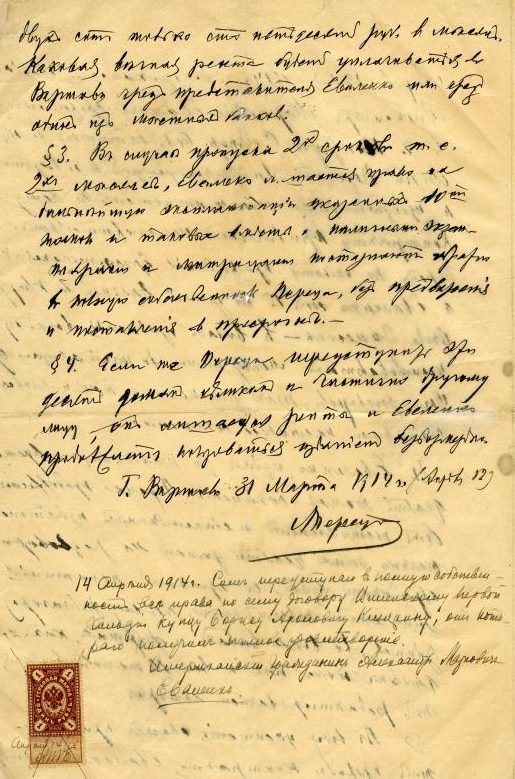

Handwritten contract for works by Yiddishist I.L. Peretz, archived at the YIVO Institute

Language itself is a key to growing knowledge and improving our perception of people and their culture, traditions, and history. In my experience, studying Yiddish expanded my horizons about European Jewish life in contemporary eras, both preceding and following the Holocaust. The biggest takeaway from my studies at the YIVO was discovering materials of importance to the Ashkenazi Jewish memory, including poetry, short stories, music, and films, some pertaining to the Holocaust. On many different levels, these materials allowed me to experience the rich history of contemporary Yiddish culture and gave me the Yiddish knowledge I needed to access YIVO’s Yiddish archival materials.

Language is also a bridge that can be built between one group and the other for mutual benefit and better visions of the future. Prior to studying at the YIVO, I received discouragement from some people who believe that Yiddish is a language of the past that is neither valued by some Ashkenazi Jews nor relevant to those without European heritage.

In fact, Yiddish culture does incorporate some Eastern elements, despite how German the language sounds. I was particularly touched by old Yiddish movies where family values and relationships between neighbors — both of which suggest a strong culture of love and caring — are well-preserved; they reminded me a lot of the social life in which I grew up between Baghdad and Istanbul.

Knowledge rewards these who seek it, both through education and experience, regardless of who they are and what cultures they come from. As a multicultural individual of Arabic and Judeo-Arabic heritage, I am honored to be part of the large movement that aims to revive Yiddish language and culture.

Learn more about Opportunity Grants supporting study abroad, language study, and research. Applications are accepted in fall and spring.

Moshé Elias studied political science with a minor in Jewish studies, and graduated in 2018. With the support of a Mitchell F. and Sophie Wise Ehrlich Opportunity Grant, he participated in a summer program sponsored by the YIVO Institute for Yiddish at Bard College. As an Iraqi native who speaks Judeo-Arabic, his interest in studying Yiddish stems from his desire to help revive this historically significant language.

Moshé Elias studied political science with a minor in Jewish studies, and graduated in 2018. With the support of a Mitchell F. and Sophie Wise Ehrlich Opportunity Grant, he participated in a summer program sponsored by the YIVO Institute for Yiddish at Bard College. As an Iraqi native who speaks Judeo-Arabic, his interest in studying Yiddish stems from his desire to help revive this historically significant language.

It is great that Ladino language is coming to the fore. Any news about judeo-arabic spoken/written in Egypt and other middle eastern countries?