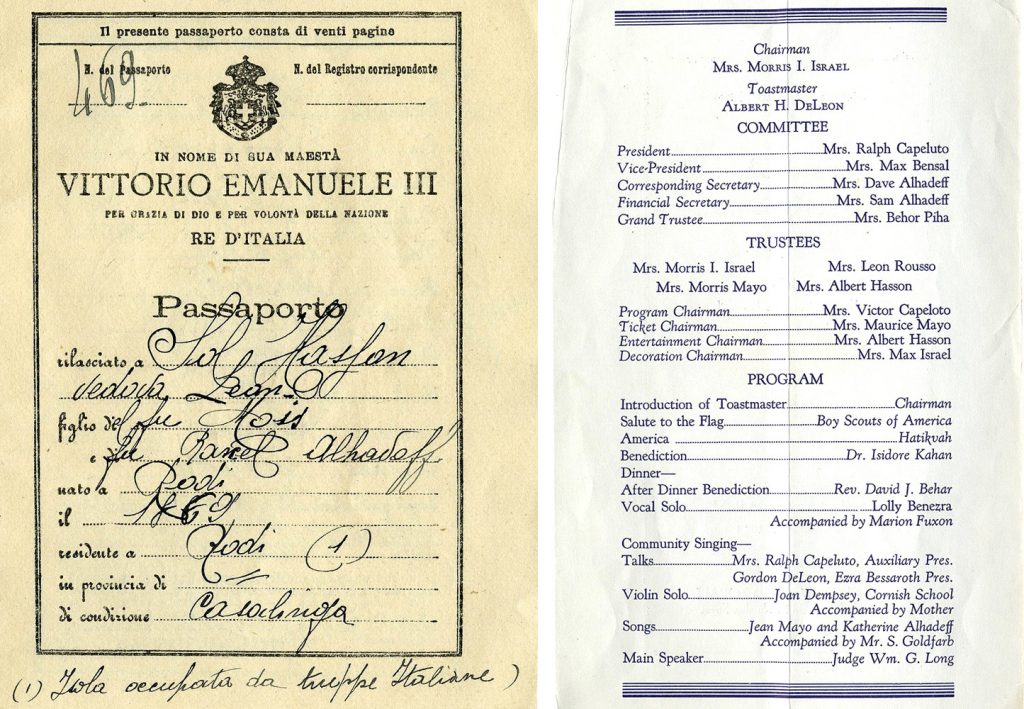

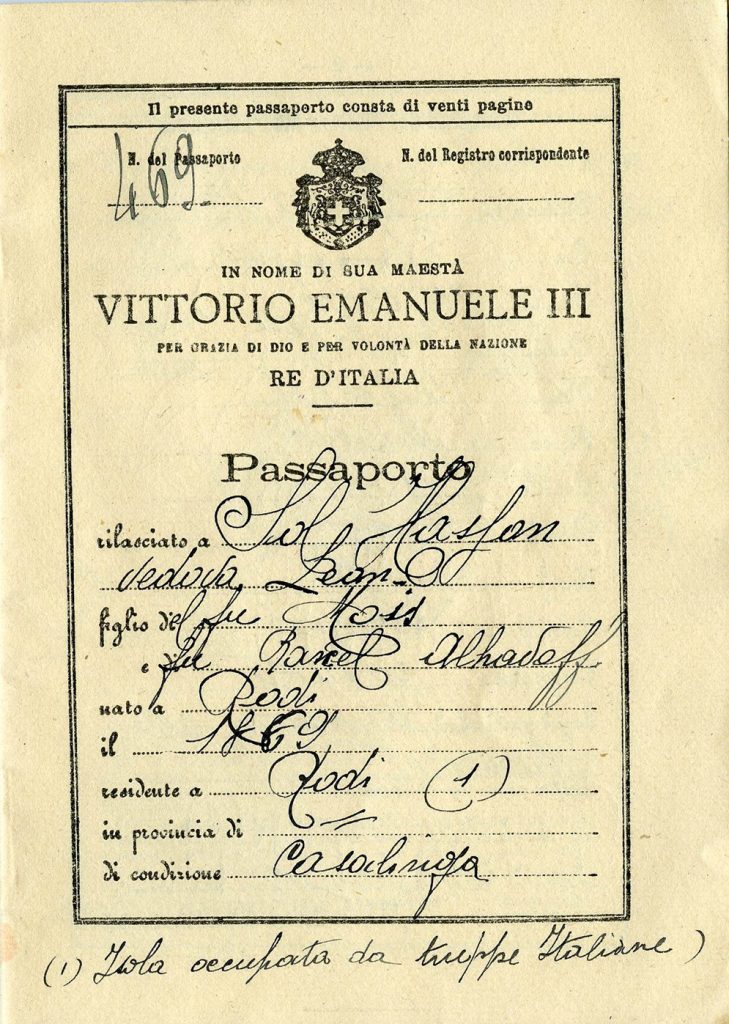

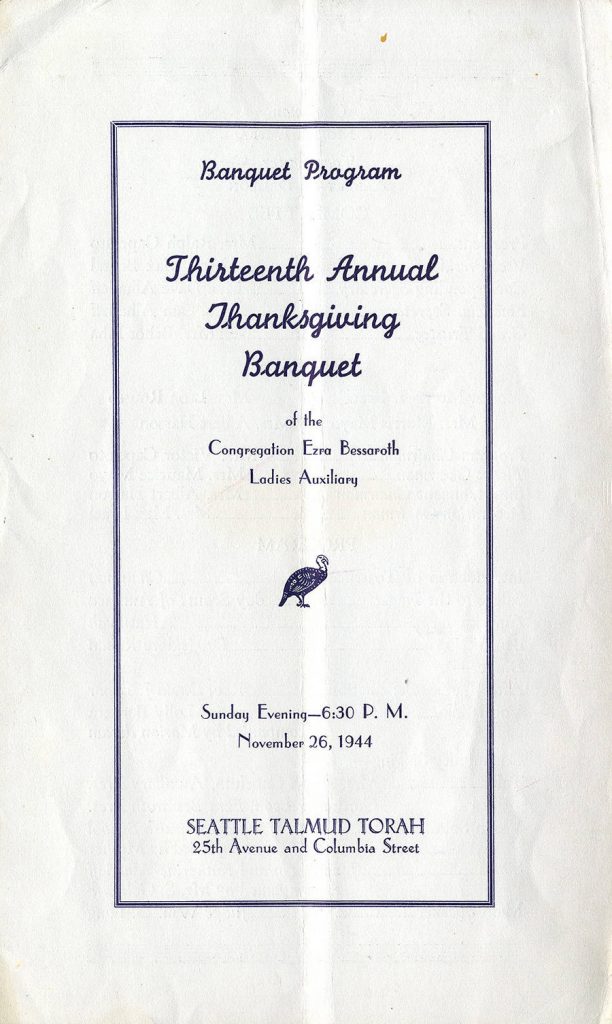

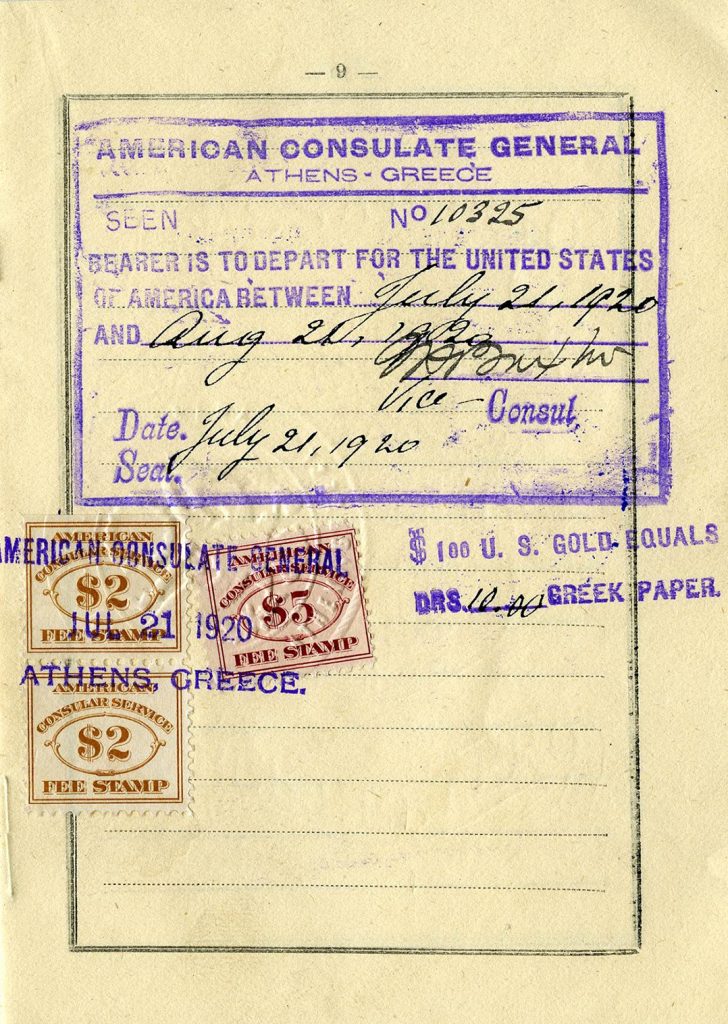

Left: Sol Hasson’s Italian passport, 1920 (item number ST001718, courtesy of Menache Israel). Right: Banquet Program, Thirteenth Annual Thanksgiving Banquet of the Congregation Ezra Bessaroth Ladies Auxiliary, 1944 (item number ST00810B, courtesy of Leatrice Guttmann).

By Lili Brown

Let’s do an exercise together. Take a moment to look at the two images of documents above.

What differences jump out at you immediately? Is it language? Is it how the papers have aged differently? Or that one is just typed, while the other incorporates both typeface and handwriting?

What similarities jump out at you immediately? Yes, they are indeed both pieces of paper. Are there any surnames present on both? Is it easier to find the differences rather than the similarities between these two documents?

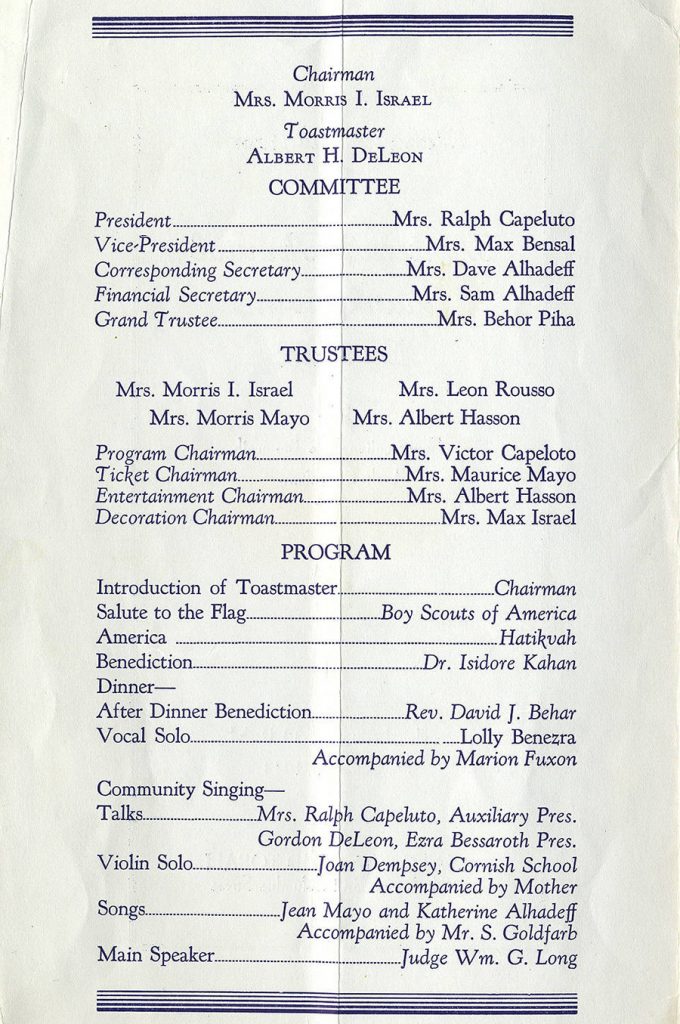

Banquet Program, Thirteenth Annual Thanksgiving Banquet of the Congregation Ezra Bessaroth Ladies Auxiliary, 1944 (item number ST00810B, courtesy of Leatrice Guttmann).

The wonder of archival material is that entire essays could be spent discussing what each of these documents communicate to us, in their own way.

The banquet program is no doubt a product of the 1940s — the event is organized by the Ladies Auxiliary, and in lockstep with the time period, the women who organized this event are identified through their husbands’ names.

A student from the Cornish School performed the violin solo — what is the relationship between this institution and the current Cornish College of the Arts in Seattle?

The passport, on the other hand, provides a snapshot of a person and their nuclear family. We learn the names of Sol’s father, mother, and deceased husband.

While a passport might seem like a transactional, impersonal format, it provides evidence of personhood, movement, and being. Where did this document allow this person to go, and who did it allow them to become?

Community archives: Offering a fuller picture of community history

As an archivist and a student of the Information School, I am not in the business of looking at these documents in isolation. There are archives, both formal and informal, that might collect these items separately; governmental agencies certainly would have copies of Sol Hasson’s passport, while a file cabinet at Congregation Ezra Bessaroth might house the 1944 banquet program.

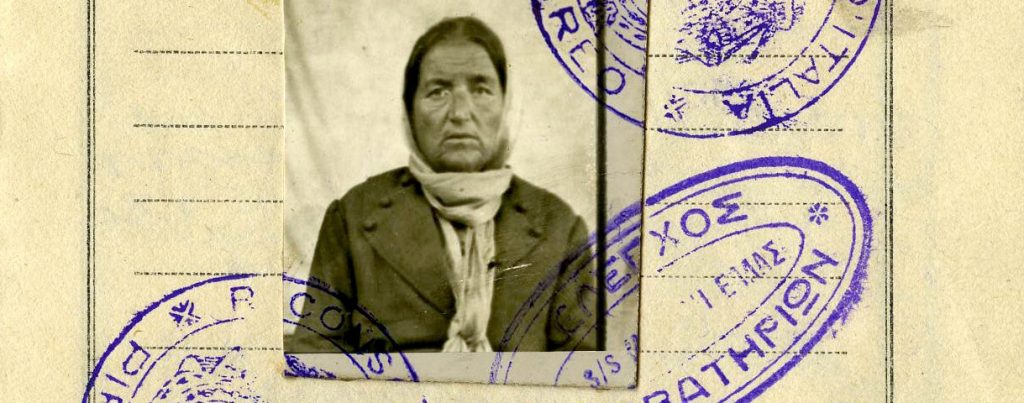

Sol Hasson’s passport photo

But a community archive — a specific type of archive organized around the many voices and materials that record a community’s history — asserts that documents of different types, languages, or timeframes need to communicate with each other. Community history is not told in one narrative, type of document, or person, because communities are composed of a collective of individuals. The archive must mirror the multitude of identities and connections that are present in the community it aims to preserve.

A community archive for Seattle’s Sephardic community is no different, and the University of Washington’s forthcoming Sephardic Studies Digital Archive, collecting photographs, documents, and objects, will be one of the first archives in the world to focus solely on Sephardic community history in the United States.

Piecing together Sephardic narratives through archival material

The Sephardic Studies Digital Archive, part of UW Special Collections, will move beyond the already-existent, robust Sephardic Studies Digital Collection to offer a digital repository highlighting the emergence and growth of Seattle’s Sephardic community, with diverse materials donated primarily by community members.

The way in which different documents and records can speak to and with each other is what draws me most to community archives. For many Jewish communities, including those of Seattle, these records serve as a foundation for vibrant Jewish life across generations. These two documents in particular materialize moments that together tell part of the story of building Seattle’s Sephardic community.

Sol Hasson’s Italian passport, 1920. (Item number ST001718, courtesy of Menache Israel)

When distinguishing between Ashkenazi, Mizrahi, or Sephardic Jewish communities in America, places of origin are paramount. We learn from her passport that Sol Hasson was born in Rhodes (see: nato a Rodi), in present-day Greece, a place many Sephardic Jews in Seattle called home before immigration.

The movement from Rhodes, and other Sephardic communities abroad, to Seattle enabled an organization like the Ladies Auxiliary to exist at an institution like Congregation Ezra Bessaroth. Where one document — the passport — begins a story, another document — the banquet program — can provide additional plot points.

Cover of Banquet Program, Thirteenth Annual Thanksgiving Banquet of the Congregation Ezra Bessaroth Ladies Auxiliary, 1944. (Item number ST00810B, courtesy of Leatrice Guttmann)

The ability to go beyond a community’s origin and find evidence of its evolution and strength, through documents like this banquet program, allows us to see the Sephardic community in Seattle beyond just its identity — what did this community do together?

The communal glue might be shared religion, but a community history archive aims to offer pieces to a comprehensive puzzle, accepting and welcoming the many dimensions its community members embodied, like gender or a new sense of nationality.

From this program, we know that the synagogue was not only a religious site, but also a site of community gathering, with groups like the Ladies Auxiliary providing social opportunities for the community, and leadership positions for women. Moreover, this social event took place on the American holiday of Thanksgiving; when it came to celebrating a holiday unique to their American identity, this community came together to do so.

Towards a Sephardic Studies Digital Archive: What’s at stake?

An archive undoubtedly becomes more complex the more types of items it houses. The Sephardic Studies Digital Archive will offer access to a variety of different materials, from textiles like generational tallitot (prayer shawls) and Ottoman rugs, to kettubot, or traditional Jewish marriage contracts.

Page 9 of Sol Hasson’s passport with stamps of travels, including a trip to America between July and August 1920. (Item number ST001718, courtesy of Menache Israel)

As a graduate student working towards a professional life in archives, I am studying archival theories and practices that can assist in making sense of complex collections like the Sephardic Studies Digital Archive.

There are multiple options for how to organize archives, with pros and cons to each, but ultimately the archive’s organization must be intuitive to its users, including community members. Here lies an additional layer to consider when creating a community archive: Who is the archive for, and who will get the most out of it? What do they need in order to access the materials?

A community-based approach that both meets the needs of its users and offers materials that community members see themselves reflected in is what makes community archives unique, purposeful, and powerful. These dually important concerns drive community archives and the collective memory they preserve.

Throughout my fellowship, I aim to help the Sephardic Studies Digital Archive become a true community archive, where anyone can come to learn more about the storied history of Seattle’s Sephardic community.

(And if you’d like to take part in this project, you can donate materials to the Sephardic Studies Program at the Stroum Center for Jewish Studies to continue amplifying the narrative of Seattle’s Sephardic community.)

Lili Brown is pursuing her masters’ of Library and Information Science at the University of Washington’s iSchool, where she is specifically studying community-focused archives. She hopes to utilize her training to better organize, curate, and source public history materials in a variety of archival spaces and historical repositories. Before coming to the UW, Lili earned two Bachelor of Arts degrees from Barnard College and the Jewish Theological Seminary, in history and modern Jewish studies. As the 2021-2022 Max Sarason Fellow in Jewish Studies, Lili is looking forward to working with the Sephardic Studies Program to help build the Sephardic Studies Digital Archive within UW Special Collections, drawing on both her knowledge of archival best practices and her experiences working with users in a Jewish history repository.

Lili Brown is pursuing her masters’ of Library and Information Science at the University of Washington’s iSchool, where she is specifically studying community-focused archives. She hopes to utilize her training to better organize, curate, and source public history materials in a variety of archival spaces and historical repositories. Before coming to the UW, Lili earned two Bachelor of Arts degrees from Barnard College and the Jewish Theological Seminary, in history and modern Jewish studies. As the 2021-2022 Max Sarason Fellow in Jewish Studies, Lili is looking forward to working with the Sephardic Studies Program to help build the Sephardic Studies Digital Archive within UW Special Collections, drawing on both her knowledge of archival best practices and her experiences working with users in a Jewish history repository.