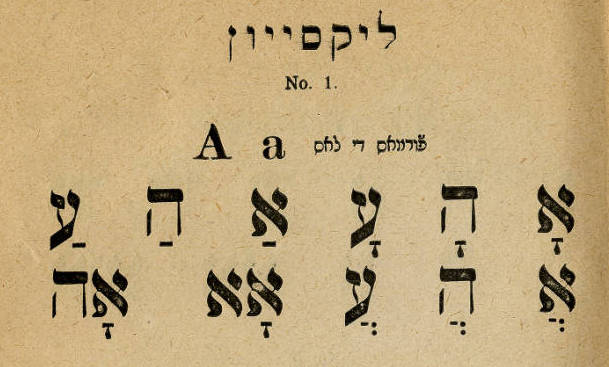

Partial page from the Magen David (ST0067), a Hebrew school book for Sephardic students. Notice that the Hebrew letter “ה” (heh, the fifth letter of the alphabet), often vocalized and romanized as “H,” receives the “A” sound in this book.

By Makena Mezistrano

Using artifacts from the Sephardic Studies Digital Collection, ‘From the Collection’ introduces the people, places, customs, and ideas that shaped the experiences of Ladino-speaking Sephardic Jews in the Ottoman Empire, the United States, and beyond. Keep up with ‘From the Collection’ by subscribing to the Sephardic Studies Program newsletter.

How did Maimonides, the medieval scholar famous for his code of Jewish law and philosophical treatises, wish his friends a “good Sabbath?” As a Sephardic Jew living in the Iberian Peninsula (today’s Spain and Portugal) and later Egypt, Maimonides may have preferred one of potentially three distinct versions of Hebrew used in the Sephardic heartland. But he would have likely used an inflection that sounded something like Shabbath Shalom — the accent at the end of his words, the final sound in Shabbath being a soft “d” or “th” sound.

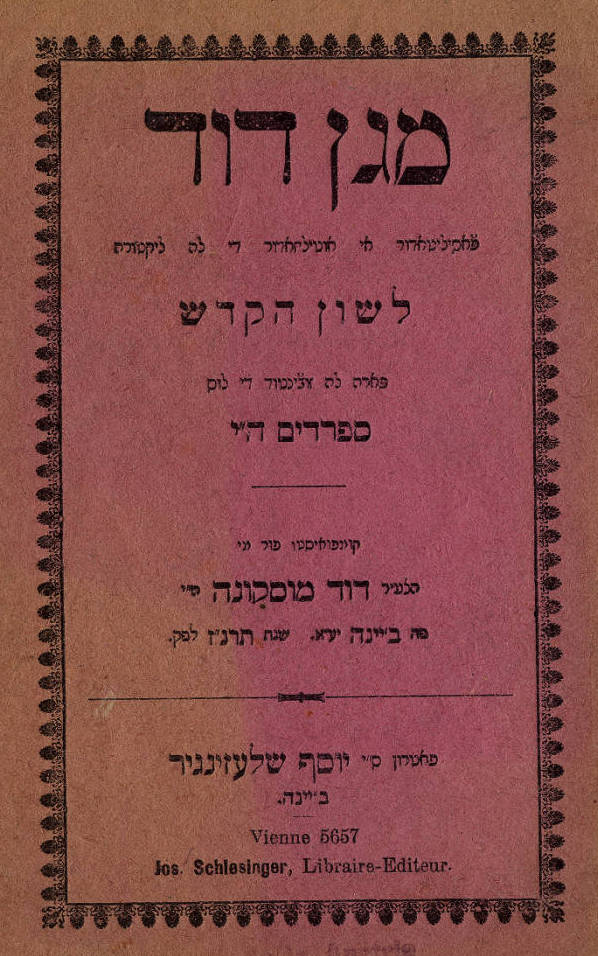

Cover of the Magen David. View the entire text online here via the Sephardic Studies Digital Collection.

Many years into the future, especially in the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, Sepharadim and Ashkenazim alike would call upon Maimonides and his Hebrew in an attempt to define — and claim — the mantle of “authentic” Hebrew for the Jewish people.

This centuries-long debate among scholars and Jewish community leaders demands, in part, a reconciliation: Whose Hebrew is “correct?” Is it that of Maimonides, or that of Eastern European Ashkenazim, who would have rendered Maimonides’ Shabbath as Shabbos? And what implications does this answer carry for defining the “ideal” identity of the Jewish people?

According to David Moskona, the Sephardic author of the 1897 Hebrew school book Magen David, Maimonides’ Hebrew — that is, Sephardic Hebrew — is unequaled. Though at first glance the Magen David looks like a regular school book, it has a clear agenda — and the very title of Moskona’s work will alert readers to the forthcoming content. In Hebrew, magen is a shield. As his Ladino introduction makes clear, Moskona’s contribution is really a defense and a protection against the Ashkenazi influence on the Hebrew language.

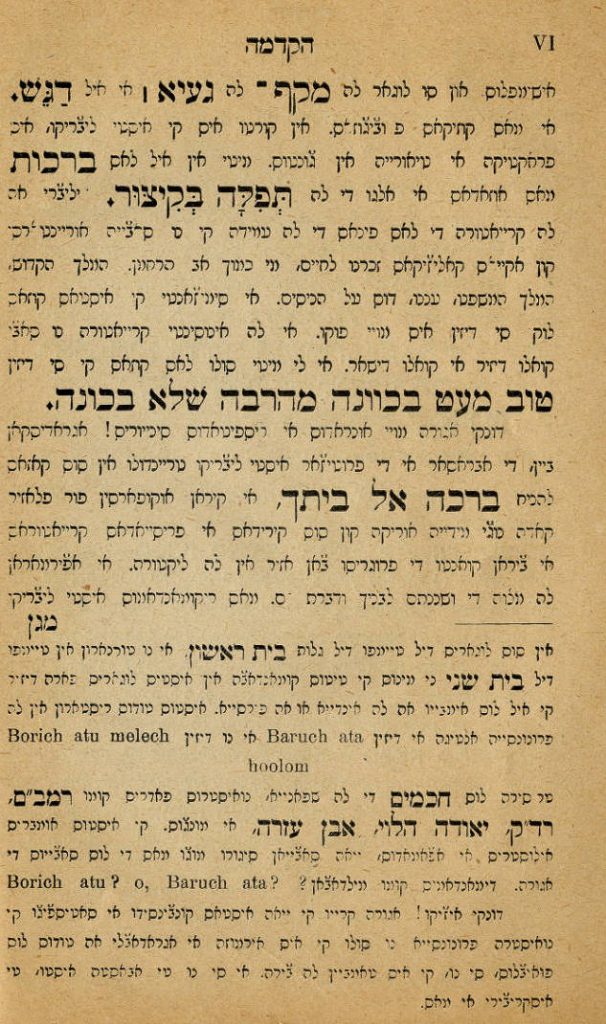

In this Ladino introduction, Moskona claims that Sephardic Hebrew is more beautiful (ermoza pronunsasion) than the Eastern European, Ashkenazi style. It is also the most authentic version of the Jewish language. “That is the truth,” Moskona writes, referring to the Sephardic inflection (of which he assumes there are only two varieties), “incontestable proof for verifying our [Jewish origins in] antiquity” (ke es la vera, provas enkontestavles por verifikar nuestra antiga).

Having established Sephardic Hebrew as the ultimate verification for Judaism in general, Moskona accuses Ashkenazi Jews of “damaging” Hebrew (lo van danyando) and clearly interprets their style of speech as a departure from its “authentic” form. Invoking an illustrious lineup of Iberian rabbis and extending their rabbinic authority to evidence an ideal Hebrew, Moskona says: “The sages of our language, our fathers like Maimonides, David Kimhi, Judah a-Levi, Abraham Ibn Ezra and more…we ask: How did they read [Hebrew]?” (los hakhamim de la safanya, nuestros padres komo Rambam, Radak, Ye’uda a-Levi, Ibn Ezra, i munchos….Demandamos komo meldavan?) To answer Moskona’s rhetorical question, these Sephardic sages would never have said Shabbos.

Moskona’s emphatic tone emerged from a noteworthy time and place. By the time he was writing the Magen David, Sephardic Jews and their style of Hebrew pronunciation had become a topic of admiration and fascination for the maskilim, members of the Jewish Enlightenment or Haskalah, a movement that emerged in Central and Eastern Europe in the late eighteenth century (and that also gained adherents in the Ottoman Empire).

Portion of Moskona’s Ladino introduction. Below the line, in smaller font, he levels his critique against Ashkenazi Hebrew. On this page, Moskona mentions several important medieval Sephardic rabbis to legitimize the pronunciation style put forth in the Magen David.

Promoting Iberian Jews’ Hebrew pronunciation brought with it major implications for defining the “ideal” identity of the Jewish people; just as this was true for the maskilim, it continues to fuel the debate about “correct” Hebrew today. The very figures that Moskona mentions — like Maimonides — became ideal Jews in the eyes of the maskilim. These Jews — and medieval Sepharadim as a whole — were celebrated as doctors, philosophers, poets, and artists integrated into and contributing to the wider society — but they were experts in Jewish law and text, too. To emulate their lifestyle meant adopting their intellectual pursuits and utilizing their version of Hebrew, as well. The maskilim not only perceived this as “the right” Hebrew, but also as the mantle of what Jewish integration into society at large should look like. The maskilim therefore encouraged all Jews, especially the Ashkenazim, to adopt it.

In addition to the broader historical context in which he found himself, Moskona was in a specifically unique position. Living and writing in Vienna, which was then part of the Austro-Hungarian (or Habsburg) Empire, Moskona was a minority in the Jewish community. Although Vienna was home to a vibrant Ottoman Jewish population and many Ladino-speaking Jews like Moskona, most of Vienna’s Jews were Ashkenazi. For Moskona, then, the differences between Ashkenazi and Sephardic pronunciation were perhaps something that he regularly encountered.

Although Moskona was Sephardic, he likely would not have been treasured by the maskilim in the same way as they treated the medieval Sephardic luminaries. With Ladino linking him to the Sephardic communities of the Ottoman Empire, Moskona would have been denigrated instead of celebrated as an heir to the Iberian Sephardic tradition and its Hebrew. His ties to the Muslim “Orient” — which carried prejudiced images of “backwards” and “uncivilized” people — would have, in the eyes of many outsiders in the West, replaced his Sephardic lineage.

When Moskona defends Sephardic Hebrew, then, he speaks to three audiences: To Jews who have attempted to strip modern, Ottoman Sepharadim from their Iberian heritage; to his Ashkenazi neighbors; and to his fellow Sepharadim.

His message to each is clear: Jews who speak Hebrew like Maimonides are still here. Moskona is one of them, and by virtue of his Hebrew, and the Hebrew of his fellow Sepharadim, his claim to that lineage is legitimate. The Sephardic students who use Moskona’s Magen David (including those in the Sephardic Jewish community in early twentieth century Seattle) will carry that Hebrew so idealized by the maskilim forward: As Moskona dutifully reminds his student readers, that Hebrew belongs to them.

Special thanks to Hazzan Isaac Azose for contributing the Magen David to the Sephardic Studies Digital Collection. Many years after its first printing, Hazzan Azose and Esther Morhaime, both prominent Seattle Jewish educators, reissued Moskona’s book with illustrations — but without its Ladino introduction — for use in the local Sephardic Religious School.

Have an artifact you’d like to contribute to the Sephardic Studies Digital Collection? Learn how to share it with us here.

Hi Makena,

As a young boy growing up in Seattle, I heard two hazzanim (cantors) in particular; Nissim Azouz (Azose), oldest son of the first rabbi of Sephardic Bikur Holim synagogue, and my uncle, Sam Bension Maimon (my mother’s brother). As a young boy, I drank in every word of their Tefilah (prayer) and I learned a lot from them. One of the things that I learned, is that, the letter ה the 5th letter of the Hebrew alphabet, had no sound. It only took the sound of whatever vowel was beneath it or above it. In other words, it is exactly like the letter Aleph א and the letter Ayin ע . It is just like the beginning illustration of your article. All the Sephardic Jews of Turkey, Greece and the Balkan countries, including the city of Vienna, where David Moskona, the author of Magen David, was from, would follow this practice. I didn’t ever think that the time would come when I would be one of the very few people who still follow this practice. I still participate in daily prayer services via Zoom and I lead some of the services. I feel blessed that, at my age, I am still able to lead and participate in the services.

Thank you again for this article. It’s only the first time that I have seen anything promoting a custom which will surely die out soon.

Hazzan Isaac Azose