Altaras-Zevulun wedding in Istanbul at the Zülfaris Synagogue (June 3, 1950). Author’s great-grandparents, Salamon and Estrula Altaras, seated on either side of the bride and groom.

By Nesi Altaras

In Rodosto (Tekirdağ), a city on the shores of the Sea of Marmara, my paternal grandfather, Nesim, lived life in Ladino. Like most Jews in Turkey in the early twentieth century, his household was so devoid of Turkish that when my grandmother, Gülten, moved to Rodosto from Adana — a major southern city — she had to learn Ladino to speak to the head of the house: her new mother-in-law, Estrula. In spite of my grandmother’s necessary adjustment, by the time my father was born, Turkish had become the primary language of the shrinking Jewish community of Tekirdağ. My father spoke Turkish at home, overhearing only the most essential words in Ladino from his grandmother.

Nearly 140 kilometers east, my maternal grandfather, Eliezer, grew up in Kuledibi (literally “by the tower”) — the most Jewish area of Istanbul and home to the famous Neve Shalom synagogue. Going to Jewish elementary school and playing with his friends on the streets around the Galata Tower — La Kula in Ladino — Eliezer spoke Ladino to friends, neighbors, and family. But when Eliezer’s sister was born, he sought to ban Ladino at his home. He wanted his sister to speak Turkish without a Jewish accent; she would face less discrimination and become a “real” Turkish citizen.

My family’s rejection of Ladino was part of a critical moment for the broader Jewish community in Turkey — and a moment shaped by the nationalist and racist policies of Turkey’s single-party state. After a 1930s tour of Edirne and Çanakkale, two of Turkey’s western cities, notorious Turkish fascist Nihal Atsız complained that Jews were flouting their obligation to the new republic by defiantly continuing to speak their own language — Ladino. While he couched his views in particularly racist terms, Atsız’s idea that citizens of Turkey — all legally deemed to be Turks — must speak the national language at all times was also the position of the state.

The Turkish Republic, formed in 1923 after the Ottoman Empire dissolved, was founded on a contract of Turkishness with two components: being a nominal Sunni Muslim, and speaking Turkish at home. For Christians and Jews, only linguistic assimilation was possible. Under the promise of equal citizenship, all minorities living in Turkey were expected to abandon their language, whether Ladino, Armenian, Circassian, Kurdish, or Greek, in favor of Turkish.

Of the various tools the Republic used to promote Turkish, one of the most effective was mandating Turkish instruction in minority schools. The Jewish school that my grandfather Eliezer attended had originally carried out instruction in French, but quickly had to switch to Turkish to accommodate new state mandates. In some areas, use of “other” languages even prompted violence.

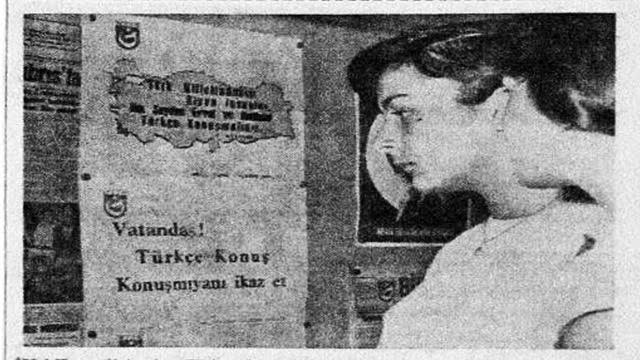

A poster from the Citizen Speak Turkish campaign. Source: Avlaremoz.

But perhaps the most visible effort to assimilate minorities into the new state was the years-long Citizen Speak Turkish campaign. Through sponsorship of public events, newspaper articles, and posters, the state endeavored to convince the entire population that to be a citizen of Turkey meant speaking Turkish. Posters declared that “should our fellow citizens falter and speak ‘foreign’ languages, we must remind them to speak Turkish.”

Genocide-surviving Armenians were suspicious of the promise of equality; Greeks, most of whom had been deported, were too proud of their own language. But Jewish elites, harboring a fear of being the state’s next target, were more than ready to become what was known as “Turks believing in Judaism” (musevi Türk vatandaşları) as opposed to just Jews (yahudi). Some Jewish leaders even became public advocates for linguistic assimilation, speaking Turkish at home and imploring other Jews to do the same — not only privately, but in their synagogue sermons and in the local Jewish newspapers. Ironically, these assimilationist agendas were by necessity promoted in French and Ladino so that they would be legible to the broader Jewish community.

The idea that Ladino was “backwards” or too “Oriental” was not new: By the 1880s, especially middle class Jews across the Ottoman Empire began to adopt French in their quest for modernity and European status (as was the case in my grandfather Eliezer’s Jewish school). The shift toward Turkish, already gaining traction by the 1908 Young Turk Revolution, may have been motivated by a number of possibilities: Some Jews were pursuing economic gain that closeness with the government, via a shared language, would provide. Others were perhaps motivated by fear, or by a genuine belief that Turkish should be their new mother tongue. Sometimes these last two factors could even coexist.

This assimilationism was so internalized over the first decades of the republic that all of my grandparents, Ladino speakers themselves, decided not to teach their language to their children. Many felt that they had no other choice. Some even sought to prevent their own parents from speaking Ladino to the next generation. The ban on Ladino that my grandfather Eliezer attempted to enforce was not completely successful, as the household included two women — Eliezer’s mother and grandmother — who spoke very little Turkish. Yet by the late 1960s and 70s, when my parents were born, families usually lived without Ladino-speaking grandparents and could easily institute Turkish as the home language.

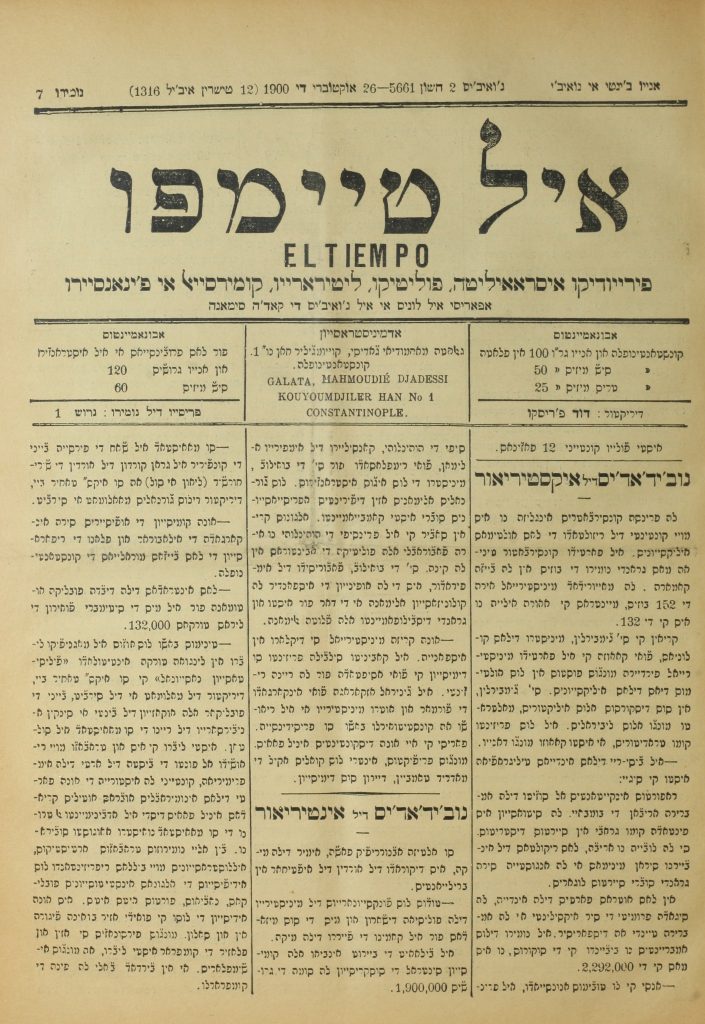

Page from the Ladino newspaper El Tiempo (ST00108), published in Istanbul. Although always a Ladino imprint, El Tiempo’s editor David Fresko advocated that his readers adopt Turkish. (Courtesy Sephardic Bikur Holim Congregation)

Jews of my grandparents’ generations, and many of my parents’ generation, were convinced of the “backwardness” or “uselessness” of their mother tongue. They had internalized the state discourse that they were Turks of Jewish faith and that as Turks it was natural, if not required, for them to raise Turkish-speaking families.

When I was growing up, none of my grandparents actively spoke Ladino: they had just gotten used to speaking — and being — Turks, even while their Turkishness was constantly questioned. Consequently, both my parents, with Turkish as their first language, were not able to pass Ladino onto me. I grew up learning only the most important Ladino words: lonso, vaziyo, kalavasucho; the occasional dicha, like “se alevantaron los pipinos i aharvaron el bahchivan.” The first two are insults (bear, dunce), the next a zucchini dish, and the dicha a saying told to disrespectful young people who might, for example, try to give their mother cooking tips (literally, it means “the cucumbers got up and beat the gardener”). The only person in my life who wanted to speak his language was my great-grandfather Pepo, who was delighted when I chose to learn Spanish in middle school over French or German.

As time went on I resented that I did not speak Ladino, the language of my community. I was angry at the government for its racist policy, and at the Jewish leaders who internalized the assimilationist agenda and foisted it upon their community.

The desire to recover my language underlines that as Jews, we are not simply Turks of Jewish faith — a conception of identity that assimilationist elites in Istanbul propagate to this day. Our language punctuates our distinctiveness as a people: we are not Turks, but citizens of Turkey deserving of equality nonetheless. A newly popularizing word in Turkish allows us to construct this new identity that includes all peoples of Turkey: Türkiyeli (“of Turkey”). But Ladino had already given us this concept in the 19th century: Turkino.

Last year, after brushing up on modern Spanish in college, and with a Ladino-Turkish dictionary in hand, I began reading Istanbul’s monthly Ladino newspaper El Amaneser — the only contemporary Ladino newspaper circulated today — and a Ladino book of essays. I began to speak Ladino with my grandparents without having to switch to Turkish — and they obliged. With the help of Professor David Bunis’ Ladino Language and Culture class this summer at the University of Washington, I hope to finally master the language of my family.

Stay up-to-date with new digital content from the Sephardic Studies Program. Subscribe to our quarterly e-newsletter.

Particular attention should be paid to groups. If you are a member of the group “pickup artist”, “how to divorce any girl for sex” and the like, first get out of them, then proceed to finding a girlfriend. Start dating on a social network should be spontaneous, preferably not with personal messages. Girls love to put up photos, commenting on them is often open to anyone, it’s a good excuse to draw attention to yourself. Rate your likes, forum hookup usa leave informative comments, ask questions under the photo. Example: if you see photos from the beach in Turkey, ask something about Turkey, try to guess the beach, the city, etc.

Nesi Altaras is an MA student at McGill University in Montreal and an editor at Avlaremoz, a Turkish online publication covering Jewish and minority topics in Turkey. His research projects include the migration of Jews from Van and Hakkari and an analysis of the use of citizenship as apologies by contemporary states. He is a student in the UW’s summer Ladino Language and Culture course with Professor David Bunis.

Nesi Altaras is an MA student at McGill University in Montreal and an editor at Avlaremoz, a Turkish online publication covering Jewish and minority topics in Turkey. His research projects include the migration of Jews from Van and Hakkari and an analysis of the use of citizenship as apologies by contemporary states. He is a student in the UW’s summer Ladino Language and Culture course with Professor David Bunis.

Mazal bueno, Nesi!

What an interesting article.. Both sets of grandparents were born in Turkey and emigrated to Cuba and then the states.. My maiden name is Behar Galico.. any advice how to connect with others with my heritage?

My grandmother Zimboul Haleva (Tacher) was born in Rodosto in 1898 and immigrated to US with Grandfather Moshe Tacher (Silivri) in 1913. She had many pictures that when I was 17 marked on back all the names, she told me to take them, I did not. My aunt Lesa Oziel Tacher donated the pictures to the UW Jewish library. How can I see and copy those pictures? Can someone tell me how and where to go on UW campus? Michael Tacher

Does anyone have any additional information about the above picture? Did the couple with the baby (Top right) live in Felek Sokak, Istanbul? Was the baby’s name Beba? Thank u