By Ke Guo

When I was taking the 2020 summer Ladino class with David Bunis, he selected a song from an old songbook named “El bukieto de romansas” for students to translate in class. As an ethnomusicologist and student of Sephardic music, I was immediately attracted to this songbook.

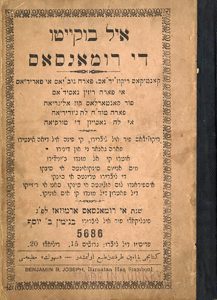

The book, “El bukieto de romansas” (איל בוקייטו די רומאנסאס), is a Sephardic song collection edited by Binyamin Ben Yosef that was published in Istanbul in 1926 and records several categories of Sephardic romansas (folk songs and poetry) that can be sung in various situations: religious songs, songs for new mothers, songs for brides, love songs that describe passion and frustrations, and songs of folk tales telling stories of adultery or of historical events. Each song is assigned a maqām (a musical scale system in Turkish and Arabic music) in which it should be performed.

The book, “El bukieto de romansas” (איל בוקייטו די רומאנסאס), is a Sephardic song collection edited by Binyamin Ben Yosef that was published in Istanbul in 1926 and records several categories of Sephardic romansas (folk songs and poetry) that can be sung in various situations: religious songs, songs for new mothers, songs for brides, love songs that describe passion and frustrations, and songs of folk tales telling stories of adultery or of historical events. Each song is assigned a maqām (a musical scale system in Turkish and Arabic music) in which it should be performed.

The undertaking of preserving orally transmitted Sephardic folk songs through writing started as early as the late nineteenth century, when scholars and print publishers began documenting traditional Sephardic songs in cities throughout modern day Turkey, with sponsorship from the Ottoman state, academic institutions, and ethnic organizations. “El bukieto de romansas” represents one part of this effort.

Now, in the present, motivated by my curiosity and eagerness to learn about the historical repertoires of Sephardic music, I hope to help carry on the tradition of preservation by transcribing and translating the entire book and making the translation available online.

The work of transliterating and translating “El bukieto de romansas”

Transliterating the songs in this collection has been a challenge. Ladino is not a unified language even today, so the spelling of words may vary for speakers in different geographic regions. Moreover, Hebrew letters and the Latin (or Roman) alphabet do not correspond exactly: For example, the Hebrew vowel “י” (yod) can represent both “i” and “e” in Roman languages, and “ו” (vav) can represent both “o” and “u.” When transcribing the text from Hebrew rashi letters to the Latin alphabet — a process called “romanization” — I have had to make decisions about how to recreate the spelling.

Without knowing the original meaning of the text, I have sometimes needed to revise spelling based on the words I am able to find in several dictionaries, such as the Ladino-English Concise Encyclopedic Dictionary (Kohen, 2000), the folkmasa online Ladino dictionary, the Ladino-French Dictionary (Nehama, 1977), and others. Some possible printing errors in “El bukieto de romansas” have also increased the level of difficulty in transcribing and translating accurately.

Since my knowledge of Ladino and Spanish (which helps in understanding Ladino) is limited, I have sought collaboration from Sephardic community members and other experts, including Paco Diez, a master musician, philologist, and a visiting artist at the UW School of Music in 2017 and 2019; Hazzan Isaac Azose, cantor emeritus of the Seattle Sephardic Synagogue Ezra Bessaroth; and Anthony Geist, a professor in the UW’s department of Spanish and Portuguese studies. I have also consulted David Bunis, maintaining our connection from summer 2020 Ladino at the UW .

While the translation project is still ongoing, I have done further research on the sonic aspect of the repertoire in “El bukieto de romansas.” How were these songs sung centuries ago? Are they always sung in the maqām as marked in the text? Although some of the songs in “El bukieto de romansas” also can be found in other Sephardic song collections, the fact that these versions are often different has made it challenging to speculate about how they were sung at the time of publishing.

With these questions in mind, I have reached out to senior researchers in Sephardic music, Susana Weich-Shahak and Judith Cohen, who have both spent many years collecting ethnographic information directly from residents of the regions around the Mediterranean Sea. Their collections of field recordings and expansive knowledge on Sephardic repertoires have helped me locate different versions of songs for comparison.

Shifts in Sephardic music: From maqam-ization to modern influences

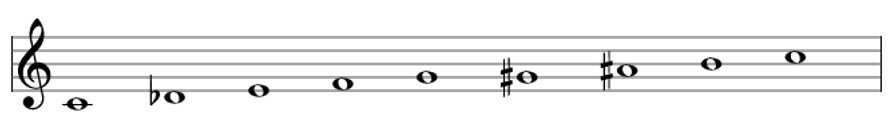

From as early as the sixth century in Byzantine regions, which included almost all of the coastal lands surrounding the Mediterranean, the Jewish liturgy went through maqam-ization — the setting of Jewish liturgical songs in the musical modes, genres, and melodies of Arab and Ottoman urban cultures. Folk music in Jewish societies was also greatly influenced by music from Islamic cultures. (The role of Jews as transmitters of the musical traditions of the lands of Islam — as composers and performers throughout history — is significant, despite the current political collisions in the Middle East.)

A frequently heard Turkish maqam in Sephardic music: Maqām Hicaz.

Maqām, a systematic use of modes with specific intervals for each maqām and a set of complex rules for composition and improvisation, has been a dominant influence in the Sephardic music played in Turkey. Although some of the songs in “El bukieto de romansas” have retained their popularity through the present in shorter or otherwise altered versions, these songs are rarely performed in the style of maqām anymore.

Modified melodies, influenced by Western classical and popular music, have prevailed in the newer interpretations of Sephardic music that people hear today. Upon comparing today’s popular recordings with the written records in “El bukieto de romansas,” it is notable that during transmission within the last century, the lyrics, melodies, and forms of these songs all have changed extensively.

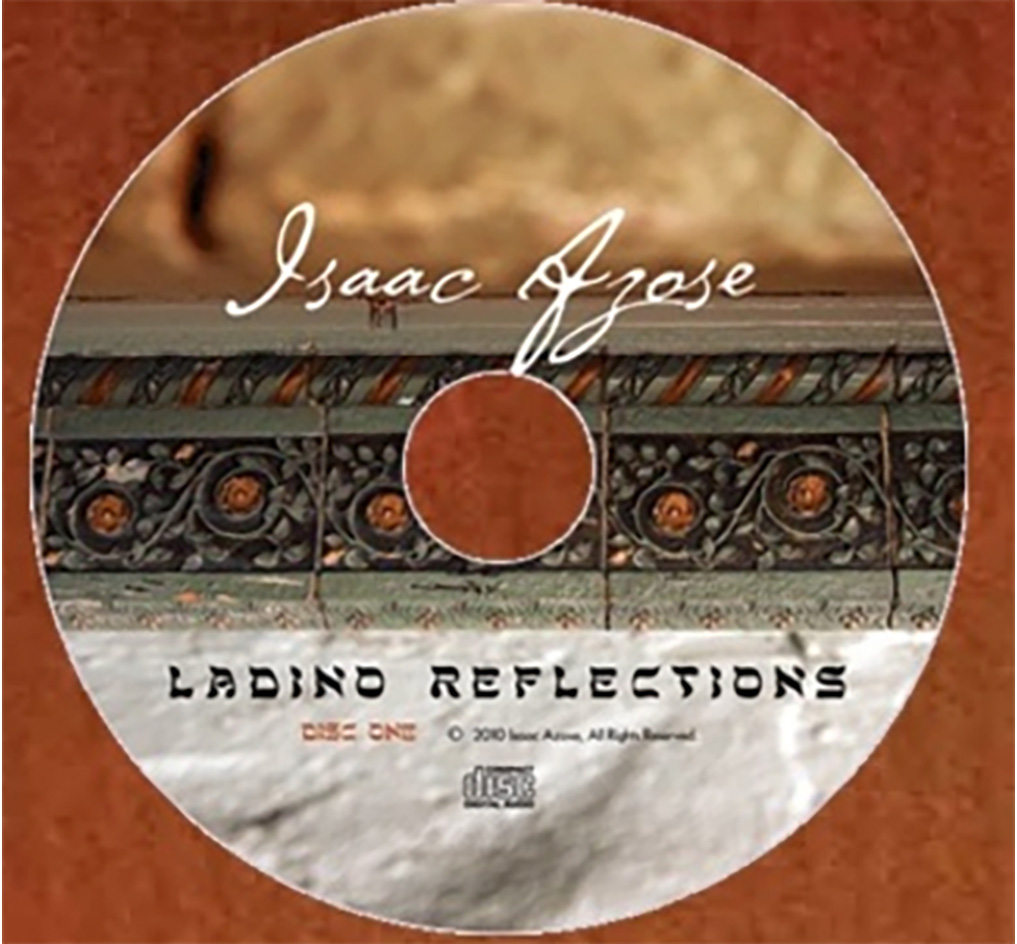

In the following example, Hazzan Azose performs “Kantika de la parida de Konstantinopla” with lyrics from “El bukieto de romansas.” Lyrics from two sources from different time periods are provided for comparison.

|

First stanza of lyrics from “El bukieto de romansas” Oh! Ke nueve mezes |

First stanza of lyrics from version sung by Aruh Palomba, recorded in 1978 Ay ke mueve mezes |

Performing & passing on Sephardic music today

Isaac Azose, Ladino Reflections (2010)

With the Sephardic diaspora moving from Europe and Anatolia (present-day Turkey) to other locations around the world, Ottoman musical styles have gradually lost favor among Sephardic communities. In Hazzan Azose’s own recordings of Sephardic non-liturgical songs, he referred to Isaac Levy’s reconstructed versions of lyrics and melodies as his main reference.

In my personal experience as a participant in musical events organized by Sephardic communities in Israel and the Americas, including Autoridad Nasionala del Ladino in Israel, singers perform Sephardic songs in popular styles that are no longer tied to Ottoman musical aesthetics. While these popular versions of melodies might preserve some elements from traditional Iberian music and Ottoman music, the approach is more of a musical mixture representing the global diaspora of Sephardic Jews than a devoted preservation of a single style of music.

Album cover via The Jewish Music Research Centre

In the past few centuries, the scenarios of performance for Sephardic romansas have also changed, from casual and domestic environments to formal and staged settings. The oral tradition, which used to be highly reliant on women within Sephardic households, has switched to multimedia recordings powered by modern technologies.

As a leading research institute in Jewish music, The Jewish Music Research Centre (affiliated with The Hebrew University of Jerusalem) has published early sound recordings of these songs, and has organized concerts performing these works for public audiences. Recently, the project “Eastern Mediterranean Judeo-Spanish Songs from the EMI Archive Trust (1907-1912)” was released in a 4-CD set, providing a direct sonic experience that can accompany “El bukieto de romansas.”

Recordings like these, along with live performances and the work of contemporary researchers, are continuing a musical tradition that was orally transmitted for centuries. By Romanizing and translating “El bukieto de romansas,” and making it available on the UW Sephardic Studies website — and in a digital edition to published on Manifold in June 2021 — as well as by recording local Sephardic musicians and performing Sephardic music myself — I hope to help carry on this tradition, as well.

Ke Guo is a Ph.D. student in music education with a focus in ethnomusicology at the University of Washington’s School of Music. She was born in Wuhan, China, and studied applied mathematics at UCLA for her B.S. degree. She then obtained an M.S. in management science and engineering from Stanford University and an M.M. in music education from San José State University. Before pivoting into music education, she worked in the consulting and tech industry. Her research in world music education and ethnomusicology has covered topics in both Chinese music and Sephardic music. As a vocalist and multi-instrumentalist, she is also active as a concert performer, and has offered individual concerts as well as collaborative concerts in America and Europe. Focusing on the topic of the worldwide transmission and reception of Sephardic music both within and outside of the Sephardic community, she is excited to conduct future field research in the Iberian Peninsula, Turkey, and other countries around the Mediterranean.

Ke Guo is a Ph.D. student in music education with a focus in ethnomusicology at the University of Washington’s School of Music. She was born in Wuhan, China, and studied applied mathematics at UCLA for her B.S. degree. She then obtained an M.S. in management science and engineering from Stanford University and an M.M. in music education from San José State University. Before pivoting into music education, she worked in the consulting and tech industry. Her research in world music education and ethnomusicology has covered topics in both Chinese music and Sephardic music. As a vocalist and multi-instrumentalist, she is also active as a concert performer, and has offered individual concerts as well as collaborative concerts in America and Europe. Focusing on the topic of the worldwide transmission and reception of Sephardic music both within and outside of the Sephardic community, she is excited to conduct future field research in the Iberian Peninsula, Turkey, and other countries around the Mediterranean.