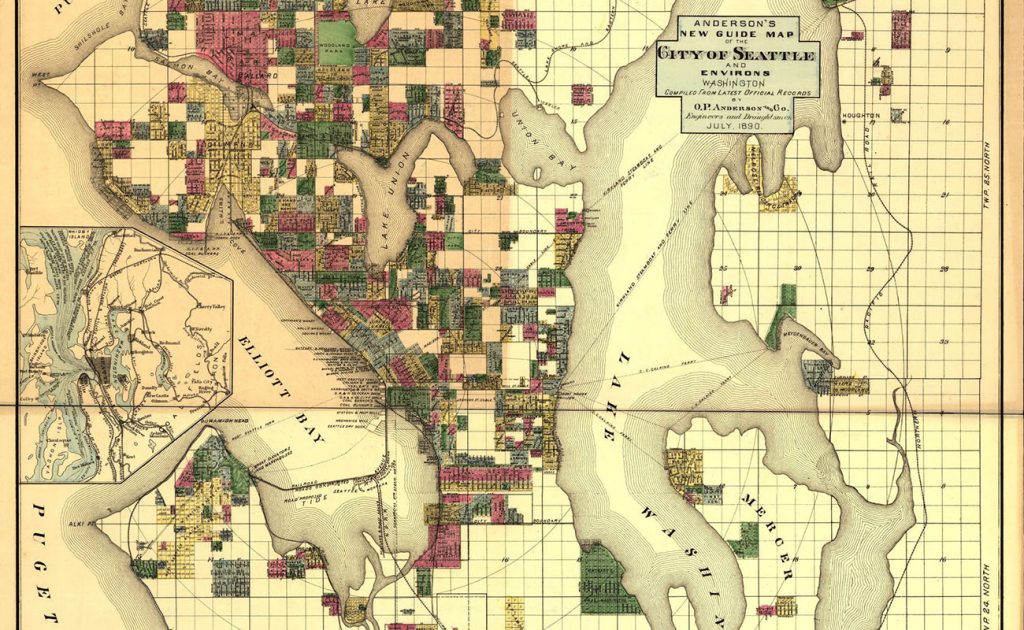

Anderson’s new guide map of the city of Seattle and environs, 1890. Via the Library of Congress.

By Oya Rose Aktaş

According to the story passed down by Seattle’s Sephardic community, the first Sephardic Jews to settle in Seattle chose this place as their new home because the lakes and the Puget Sound reminded them of the Marmara Sea and the Bosphorus Straits in Turkey. They worked in Pike Place fisheries, built communities in the Central District and Seward Park, and constructed the Ezra Bessaroth and Bikur Holim synagogues. They built relationships with their neighbors and witnessed the hardships that they experienced, such as the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II.

As a Ph.D. student in history who researches Jews of the Ottoman Empire at the turn of the 20th century, I wanted to see how this story lined up with the historical record. I went as far back in the history of migration to Seattle as I could to learn more about this period in Seattle and see if there were any parts of the story that had not been passed down.

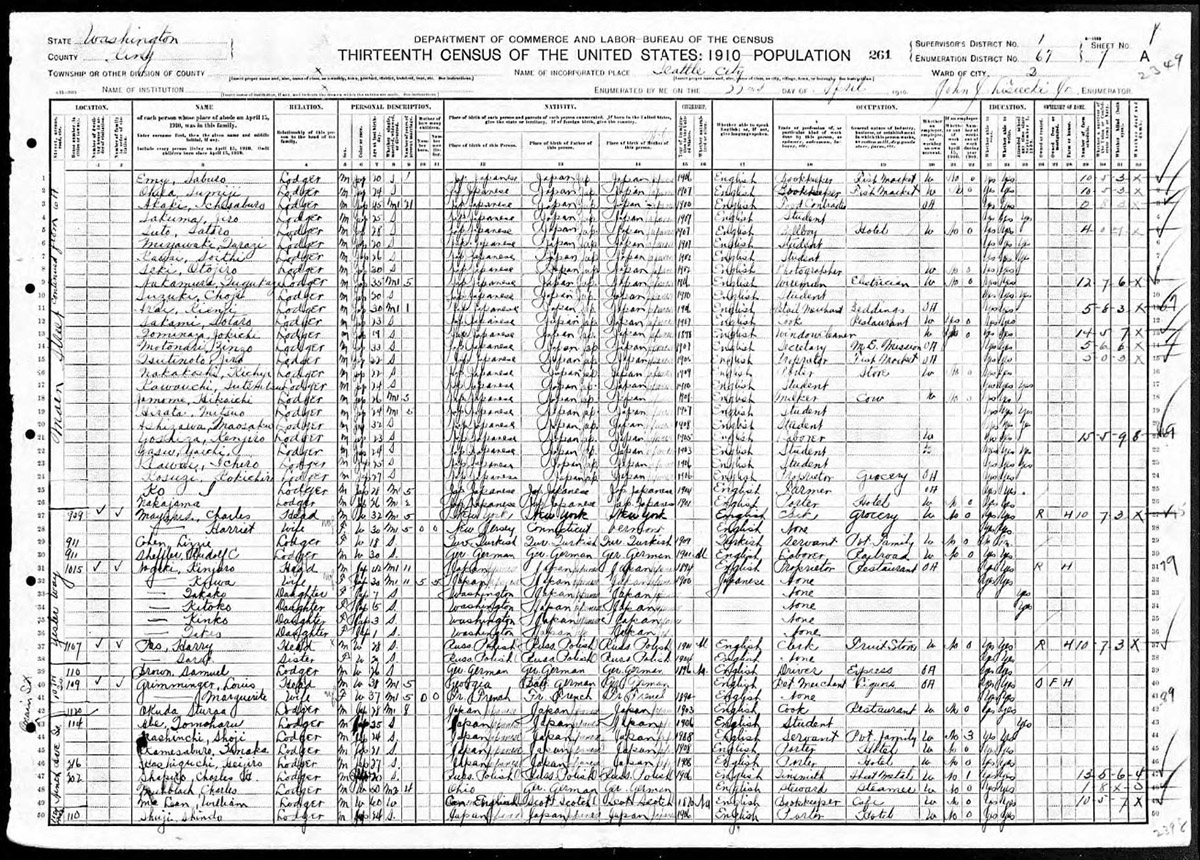

In doing this research, I learned that Sephardic Jews were one of many groups who were migrating to Seattle at the turn of the twentieth century, and they were not necessarily the first to arrive from the Ottoman Empire. I dove into census records from the turn of the twentieth century and collected information on people who were listed as born in “Turkey” (which at the time encompassed modern Turkey, parts of the Balkans, and the Levant, the eastern Mediterranean region between present-day Turkey and Egypt).

“Turkish” residents of Seattle before 1900

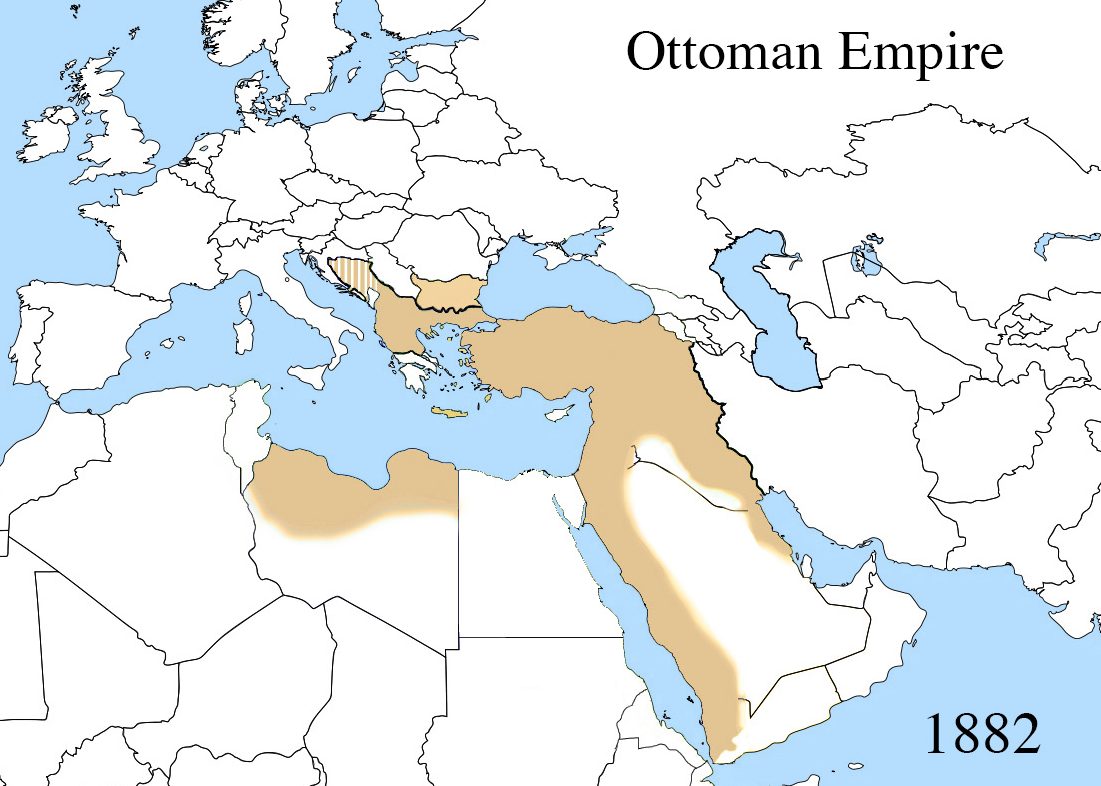

Map showing the Ottoman Empire in 1882. Adapted from Wikimedia Commons.

Before 1900, there were only three Turkey-born settlers in Seattle: M. Abraham and Nassir Khalil, who were both listed as peddlers — traveling salespeople, a common profession for Arab Christian immigrants from Lebanon — and Emma Josenhans, whose American-born parents were missionaries in Turkey (likely working to convert Orthodox Armenians to Protestantism), and whose architect husband would design many buildings on the University of Washington’s Seattle campus.

By the time the Washington Territory became Washington State in 1889, only Emma remained in Seattle, while Nasser and M. Abraham had either moved on or passed away. By the 1900 census, there had been a slight bump in “Turkey”-born Seattle settlers: There were a total of 17 people listed as born in “Turkey,” six of whom belonged to the same “Melkey” (Milakee) family. Most of these settlers were likely Lebanese, and held working and middle-class occupations, including a waiter, a storekeeper, a hotel cook, a day laborer, a peddler, and a cigar merchant. There were also three Jews in this first wave of Turkey-born settlers, whose parents were all originally from Russia.

“Turkish” residents of Seattle in 1910

In the following decade, there was an explosion in migration from the Ottoman Empire to Seattle. The 1910 census listed 548 Seattle residents as having been born in “Turkey” — representing an over three thousand percent increase from the previous census.

| Census Designation | Male | Female | Total | Percentage of Total Seattle Population | Total Seattle Population |

| 1900 “Turkey”-born population | 10 | 7 | 17 | .02 % | 80,671 |

| 1910 “Turkey”-born population | 483 | 65 | 548 | .23 % | 237,194 |

Census information from HistoryLink.org — 1900, 1910

Only 65 of these residents, or just over 10 percent, were women. The majority of the women who had migrated were Jewish, followed by Syrian, Greek, and Armenian women, all of whom were listed as the daughters, wives, mothers, nieces, sisters, and sisters-in-law of the heads of house.

Of all of the women recorded in the census, only one Jewish woman, Lizzie Cohen, was classified as a “lodger” residing with a local family, with “servant” listed as her occupation. Along with two other Jewish women listed as “dressmakers,” Lizzie was one of the few women to undertake paid labor. Two other exceptional women were Anna Joseph and Asma Ablan, Assyrian and Syrian, who were the only women listed as “heads” of their households by the census.

The hundreds of men who immigrated to Seattle in this period were identified as having even more diverse ethnic backgrounds, and worked in a wide range of professions. In addition to Jews, Greeks, Armenians, Assyrians, and Syrians, there were Bulgarians, Albanians, Macedonians, and Roumanians who had immigrated from the Balkans. The majority of these men were working class, most commonly listed as “laborers,” with “shoeshiners” as the second most common profession.

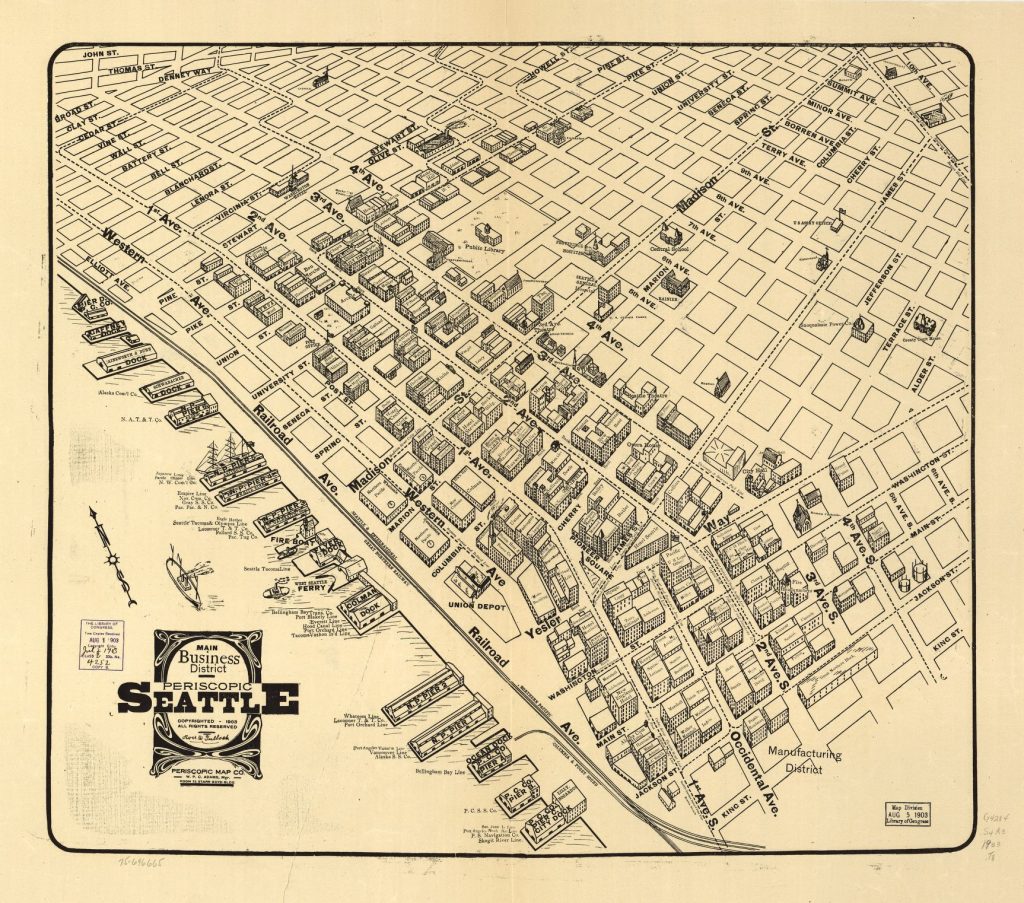

In addition to these low-wage trades, the census lists professions that would have catered to emerging communities and families. Armenians and Greeks living in Queen Anne, Wallingford, and Pike Place worked as bakers. Greek restaurant proprietors living by the waterfront along Pike Street supported the growing Greek restaurant industry. The census even includes Armenian ice cream peddlers living along Denny Way, who must have been inspired by a growing number of families and children.

Unlike the 1900 residents, who spent time in other parts of the United States before settling in Seattle, many of those listed in 1910 had arrived in the country very recently, and likely immigrated with Seattle as their intended destination. This reflects two big shifts for Seattle in the first decade of the twentieth century: increasing international recognition, and a booming settler population.

The impacts of increasing settlement

Both of these shifts had severe consequences for the natural environment, and the Duwamish and other Coast Salish peoples who had lived on and cared for the lands and waters for thousands of years. The tidal flats that had housed shellfish and the hills that overlook these flats were subject to aggressive regrading projects, which leveled the area of present-day Seattle now called Belltown and filled in the waterfront we now know as Elliot Bay during the first decade of the twentieth century.

Main business district, Seattle, 1903. Via the Library of Congress.

Indigenous symbols and practices were co-opted into advertising this growing metropolis — with events such as the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition, a 1909 world’s fair held on the University of Washington’s campus — as longhouses were erased from the landscape.

Racial segregation in the housing market also increased, with covenants and other policies restricting the areas in which Black, Asian, and Jewish residents could live and limiting some people of color, particularly Black Seattleites, to buying and renting homes in the Central District.

Seattle’s Sephardic community

While Seattle’s Sephardic community contributed to, and was affected by, these changes in complex ways, Sephardic experiences have always been woven in with groups from other religious, linguistic, and racial backgrounds.

My dive into historical census records reveals the different identities that Seattle’s Sepharadim have taken on over the years: Spanish-speaker, fishmonger, shoeshiner, dressmaker, Jew, and even Turk. But I also learned that these identities always intersected with other groups, whether they were fellow Ottoman settlers, multilingual Turkish speakers, or neighbors in the Central District.

Although stories that traverse these different groups are not passed down as readily, searching for these connections can show how our identities change over time, and open up new ways of thinking about our collective past.

Oya Rose Aktaş is a Ph.D. student in the University of Washington’s Department of History studying non-Muslim communities in the transition from imperial subject to liberal citizen in the late Ottoman Empire and early Turkish Republic. Her current research focuses on how state violence targeted at Christians affected the position of Jews in Istanbul, and her project for the Stroum Center graduate fellowship will include work on the Sephardic diaspora in Seattle, Washington. Prior to graduate school, Oya worked on U.S. foreign relations and economic policy at Washington DC think tanks.

Oya Rose Aktaş is a Ph.D. student in the University of Washington’s Department of History studying non-Muslim communities in the transition from imperial subject to liberal citizen in the late Ottoman Empire and early Turkish Republic. Her current research focuses on how state violence targeted at Christians affected the position of Jews in Istanbul, and her project for the Stroum Center graduate fellowship will include work on the Sephardic diaspora in Seattle, Washington. Prior to graduate school, Oya worked on U.S. foreign relations and economic policy at Washington DC think tanks.

I may have some additional information. My mother’s father’s first wife was a Lizzie Cohen. He was Isaac Baroh. She was also my father’s mother’s sister Sultana Cohen Morhaime. With brothers Bennie Cohen and Joseph (Joe) Cohen.

Also my dad’s sister Rebecca Morhaime Moshcatel was the first Sephardic Jewish child brought to Seattle.

My grand Oncle, Aharon Mizrahi, left Turkey around 1905 and moved to seattle.

I know he worked in the fishery business.

Did you came across his name while doing your study ?