The Galata Bridge spanning the Golden Horn inlet of the Bosphorus River in Istanbul (present-day Turkey), circa 1895. Via Wikimedia Commons.

By Oya Rose Aktaş

On April 24, 2020, the 105th anniversary of the 1915 Genocide was commemorated in the United States with an additional layer of acknowledgement, after the U.S. Senate voted in December 2019 to officially recognize atrocities committed by the Ottoman Empire against Armenian, Assyrian, Chaldean, and Greek Christians during and after World War I as constituting genocide.

Echoes of this violence can be found right here in Seattle, in an oral history project conducted in the 1930s at the University of Washington. Sephardic Jews from the Ottoman Empire began moving to Seattle at the turn of the 20th century. One of the Istanbul-born Sephardic Jews who came to the U.S. in this wave of migration, Albert Adatto, was a student at the University of Washington who grew up in Seattle’s Sephardic community and decided to devote his 1939 masters’ thesis to documenting Sephardic life in Seattle and the United States.

The thesis, titled “Sephardim and the Seattle Sephardic Community,” described the history, culture, and composition of Seattle’s Sephardic community. At the end of this thesis, Adatto included a transcript of interviews that seemingly had nothing to do with Sephardic life in Seattle: They were interviews about the Armenian massacre of 1896.

Violence targeting Armenians in the late Ottoman Empire

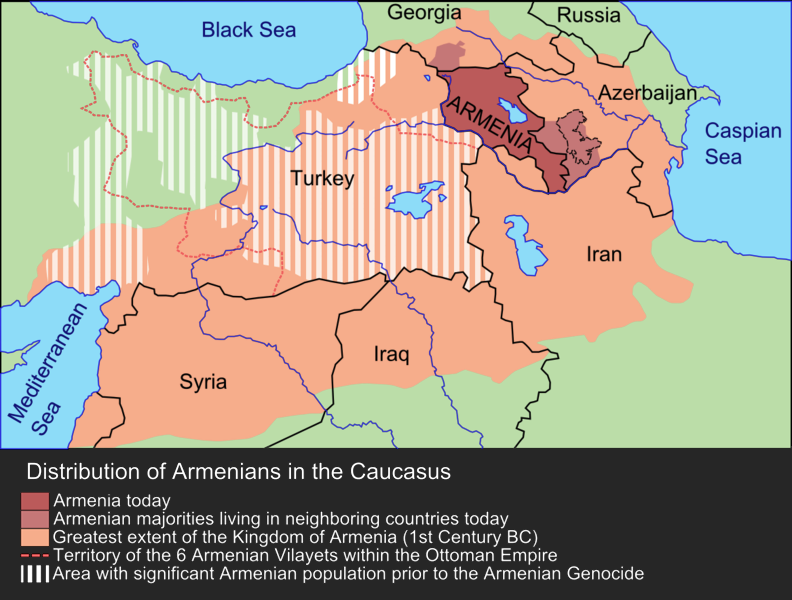

Armenians remember the 1890s massacres as the beginning of the decades-long process that culminated in the 1915 Genocide. Most of the violence was concentrated in the eastern provinces of the Ottoman Empire, near the border with Russia, which had been ruled by Armenian kingdoms in antiquity. The Ottoman sultan, Abdülhamid II, sponsored brigades that attacked Armenian villages in order to stamp out nationalist movements and perceived opposition to the sultan. Although areas that were more readily incorporated into Ottoman economic networks were spared this violence, villages farther from the sultan’s reach became targets of massacre and pillaging.

Distribution of Armenians in the Caucasus, past and present. Via Wikimedia Commons.

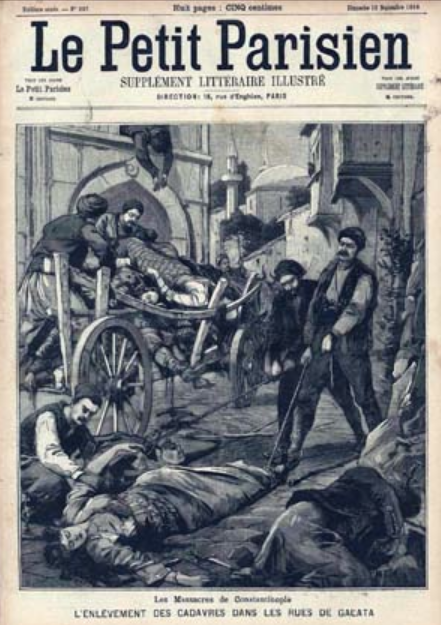

In 1896, this violence spilled over into the Ottoman capital of Istanbul when a group of Armenian revolutionaries staged an armed occupation of Istanbul’s Ottoman Bank to draw attention to massacres against Armenians in the provinces. This takeover triggered attacks against Armenians living in the capital over the next few days. These attacks left such a strong impression on Jewish residents of the city that three decades later and six thousand miles away, four Seattle residents chose to recount what they had witnessed to Albert Adatto.

Remembering the 1896 massacre

From Albert Adatto’s interviews, we learn that many Jews protected Armenians in Istanbul during the 1896 massacre. One interviewee, Sam Adatto, noted, “I knew of a few Jewish families in Galata [the district where the Ottoman Bank was located] who hid their Armenian friends until the excitement was over.”

Another, Dorah Cohen, recalled, “Many Armenians were killed but we Jews saved many from death because we loaned them religious garments and phylacteries in order that they would pass as Jews.” Jews in Istanbul extended shelter and Jewish symbols to their Armenian friends and neighbors to protect them from the immediate violence surrounding them. The accounts also mention instances of Turks protecting Armenians, but perhaps passing as Jewish was easier or less subject to scrutiny than passing as Muslim.

Reading the accounts more closely suggests that the violence left a lasting effect on the Jewish residents of Istanbul as well. Anna Adatto, who was just a girl at the time, went out with her friend shortly after the massacre began to see what was happening. Her neighbor yelled at them “to return home at once because of the grave danger.”

“L’enlevement de cadavres dans les rues de Galata” — “Gathering bodies in the streets of Galata” in the Parisian weekly Le Petit Parisien. September 13, 1896. Via the Armenian Genocide Museum Institute.

Anna recalls, “Just as we approached our home we looked up at a nearby wall and saw a Turk with a huge stick knock down an Armenian. It appeared as if the Armenian was killed instantly.” For such a young person to witness such sudden death must have left a lasting impression. Sam Adatto remembers seeing Armenian porters being killed in Galata, and being so afraid that he went home and “never went out again for twenty four hours. It was a horrifying experience.” These horrific memories stayed with the interviewees for decades to come.

The interviewees disagreed about the impetus behind the violence. Albert introduced his interview transcripts with the observation, “This writer has talked with several other Sephardim who were in Stambol [Istanbul] in 1896 and the general consensus seems to blame the Armenians for the uprisings and condemn the Turks who participated in the riots.” Indeed, Sam Adatto remarked, “Those who attempt to overthrow the government are not good. The same with the Armenians. I liked many Armenians, but I do not like the idea of forcing a revolution on any government.”

Another interviewee, Shomuel Brudo, had a much more skeptical impression: “The Armenian massacre in Constantinople [another term for Istanbul] is a very delicate question and to pass judgment will be almost impossible. Personally I sympathized with the Armenians and felt they should be granted political autonomy.” Although many of the interviewees sympathized with the suffering of Armenians, Brudo was alone in sympathizing with their political aspirations.

Framing violence in terms of class

The language that interviewees used in referring to the violence is also significant, because it frames the victims as culpable, and removed from the interviewees themselves. The people that found fault with Armenians emphasized the fact that the perpetrators and the victims were all lower class. They used terms like “fighting” and “rioting,” rather than “massacre.”

During her interview, Anna Adatto noted, “Turks prior to the fighting called the Armenians, ‘rats’ and after the fighting it seems as if the Armenians disappeared like rats because there was not a sign of them anywhere.” She also ended her interview by saying, “The Armenians were often called ‘Politica Daimem’ and were very skilled politicians.” These damaging stereotypes minimize the violence that Armenians faced, and suggested equivalent actions on both sides, despite Sam Adatto’s acknowledgement that “…of all the people that were killed that day only one per cent were Turks, the rest were Armenians.”

The interview transcripts exhibit this class-based distancing within the Jewish community as well. Anna Adatto recalled, “I know that some of the lower class people in our district were guilty of looting. There were also two lower-class Jews who participated in looting and they were ostracized by the neighbors. No good ever came to them because they were cursed by the stolen goods.”

The references to class in the testimonies indicate that the victims, the perpetrators, and the profiteers of the violence that took place in 1896 were from the more-vulnerable working class. By 1915, however, class privilege no longer protected people from the genocide. The Armenian intelligentsia was one of the first targets of the Ottoman Empire’s genocidal policies, and the orders came from the highest echelons of the Ottoman state.

Going beyond heroes and villains in reading history

Scholars rarely study shared histories of Jews and Armenians. One of the few exceptions is Julia Phillips Cohen, who considers the ambivalent relationship between the two groups in the Ottoman Empire in the 1890s in her book, “Becoming Ottomans: Sephardi Jews and Imperial Citizenship in the Modern Era.” Phillips Cohen uses letters and newspaper articles, as well as the testimonies above, to demonstrate how Jews helped Armenians in private but did not want this aid to be publicly acknowledged. In my own research, I try to understand the complex dynamics of this ambivalence, particularly by acknowledging people’s class positions.

When we study history, particularly histories of violence, it is tempting to try to find the “good guys” and the “bad guys.” Reading these testimonies has been a reminder for me that people react to violence in ambivalent, contradictory ways. Understanding complicated reactions to violence by groups that are not openly targeted by state-sanctioned attacks, like Sephardic Jews in the late nineteenth century Ottoman Empire, can help us recognize the divisive effects of violence.

We can acknowledge interviewees’ fear of challenging state power, while also identifying the problematic stereotypes that factor into their reflections. Dismissing violence as the purview of the working class, or a particular ethnic/racial group, is a prevalent trope that occludes deeper structures of violence.

By puzzling through these ambivalences, we can begin to recognize how broader groups become implicated in state violence, which in turn forces us to reflect on our collective responsibilities when it comes to supporting groups targeted by the state.

Oya Rose Aktaş is a Ph.D. student in the Department of History studying non-dominant populations in the late Ottoman Empire and early Turkish Republic. Her current research focuses on how state violence targeted at Christians affected the position of Jews in Istanbul in the decades before and after World War I. Prior to graduate school, Oya worked on US foreign relations and economic policy at think tanks in Washington, D.C.

Oya Rose Aktaş is a Ph.D. student in the Department of History studying non-dominant populations in the late Ottoman Empire and early Turkish Republic. Her current research focuses on how state violence targeted at Christians affected the position of Jews in Istanbul in the decades before and after World War I. Prior to graduate school, Oya worked on US foreign relations and economic policy at think tanks in Washington, D.C.

Leave A Comment