The Golem Cafe taps into the local Jewish legend of a creature made of clay who is brought to life by mystical powers. Photo by Sarah Zdancewicz.

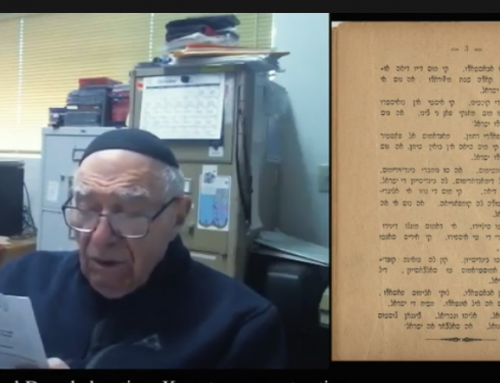

By Sarah Zdancewicz, 2013 Student Travel Grant Winner

From the moment I decided to minor in Comparative Religion my freshman year, I knew I wanted to study religion abroad at some point in my college career. However, I found that there were no previously established programs in this area of study, so the idea of planning my own trip began brewing in my mind. When I saw the flyer for the Jewish Studies travel grant hanging on the board above the water fountain, it served as that final push I needed to put my dream into motion.

Although my minor covers many religions, I have found myself taking classes geared more towards Judaism and the Jewish people. I’m a studious person, but I also wanted to gain knowledge that cannot come from a book. Traveling through Europe last summer, I was able to integrate my studies with real-life experiences and explore different parts of the world.

I started my independent study abroad trip in Prague, a city with the well-known Jewish Quarter of Josefov, that still has many of its important buildings intact. While the reason for this is unfortunate (Adolf Hitler wanted to keep the area preserved to serve as an extinguished race museum), it allows viewers today to go back in time and better visualize an earlier Jewish Prague.

During the time of my stay, the city reached all-time record high temperatures, and boy could you feel it. The majority of the tour is indoors; however, with no A/C it’s almost worse inside. I would recommend visiting closer to June or September rather than July or August because it does make it hard to focus on the sites when all you want is another Coca Cola.

The Ceremonial Hall in Prague’s Jewish Quarter preserves the site of the community’s chevra kadisha (burial society). Photo by Sarah Zdancewicz.

There are seven main Jewish sites to visit: the Maisel Synagogue, the Pinkas Synagogue, the Old Jewish Cemetery, the Klausen Synagogue, the Ceremonial Hall, the Spanish Synagogue and the Old-New Synagogue (Altneuschul). One ticket allows entrance into all of these places, except for the Old-New Synagogue; you can either buy a separate ticket if it is the only synagogue you wish to see or buy a combined ticket of all seven sites for a greater price. The latter is what I ended up doing, and for an entrance ticket, an audio guide, and a student discount on both, the total ended up being $25. I listened to just about every clip and was able to view them all in a day, but for the average traveler, I would say 2-3 hours is sufficient time for the experience.

Also, prospective visitors should be aware that there are no photographs allowed in any of the locations, with the exception of the Old Jewish Cemetery, at which you can pay a small fee for permission. There were some opportunities where I would have been able to sneak in some photos, but felt that the nature of it was disrespectful and opted to just enjoy everything in that moment instead.

The first stop was the Pinkas Synagogue. It had been used as a synagogue from the 16th century until World War II, after which it became a memorial for the Jews of Bohemia and Moravia (modern-day Czech Republic) who perished in the war. Before the war, about 117,000 Bohemian and Moravian Jews were living in this land and about 25,000 managed to escape. However, 80,000 are known to have been victims of the Holocaust, and it is the names of these 80,000 that have been written inside the Pinkas Synagogue on the walls in their memory. For me, even more moving was the exhibition upstairs that displayed paintings of children who lived in the Terezin ghetto/concentration camp from 1942-1944. There are several different “categories” of drawings, such as “Coming home,” “On the outside,” and “Life inside the ghetto.” Many of the children did not survive, which makes their drawings of hope even more heartbreaking.

The next stop was the Old Jewish Cemetery, a display of crooked tombstones in a raised section of land. The Jews had been allotted a limited area of land in Prague, and because more and more people were dying, in order to be able to bury them correctly they had to be buried in layers. While some tour guides may say it is 12 layers high, the real answer is 5 (says the audio guide from the museum, but maybe they are wrong too). Each tombstone therefore has multiple listings, done in corresponding order. Some famous people buried in this cemetery include Rabbi Judah Loew ben Bezalel, also known as the Maharal of Prague (ca. 1525-1609); community leader Mordecai Maisel (1528-1601); and the astronomer David Gans (1541-1613). Loew’s narrative of the Golem and its influence was not as present in the area as I would have thought, with the exception of the “Golem Cafe” nearby. It could have just been a bias I encountered, but I saw that the figure given the most attention was the mayor Mordecai Maisel.

Moving on to the Ceremonial Hall, you will find remnants of the Prague Burial Society (chevra kadisha). The majority of items you will find are silver instruments that were used in preparing the dead, along with a very well preserved board that was actually once used in this preparation. I also found the Klausen Synagogue to be very well organized and interesting, with displays portraying different holidays, traditions, and rituals that showed the continuing traditions in relation to the past.

The Spanish Synagogue incorporates Moorish design and is located on the site of the former Old Synagogue. Photo by Sarah Zdancewicz.

However, I would have to rate the Spanish Synagogue as the most beautiful building in Josefov. The exterior is indeed beautiful, but walking inside you are blown away by the details and design. Though only built in the 19th century, the Spanish Synagogue is built on the location of the former Old Synagogue, which would have been the oldest synagogue in Josefov had it not been destroyed. The Moorish design and bright colors fill every space of wall and ceiling and displayed are documents and the like detailing Bohemian and Moravian Jewish history from the 18th century until the present.

The Old-New Synagogue was next on the list for me. It is the oldest active synagogue in the world, making it a pretty special place to visit. Legend has it that the pieces of Loew’s Golem are still up in the attic, but that’s obviously not able to be visited. Compared to the other synagogues in Josefov, this is a very small space, but luckily I was able to overhear a tour going on and learned some intriguing tidbits about certain details of design.

Prague’s Old-New Synagogue is the oldest active synagogue in the world. The attic is rumored to contain pieces of the famous golem. Photo by Sarah Zdancewicz.

Lastly I finished my self guided tour at the Maisel Synagogue, financed by Mordecai Maisel and built during the Jewish Prague Renaissance of the 16th century. Inside, its display cases featured the history of Bohemian and Moravian Jews from the beginning of their presence in the area until the 18th century.

The impression I got after visiting Josefov was that while there is still a presence of Jewish culture in the area, it mainly exists as a tourist attraction. I tried to speak with a couple of members working at the various sites, but unfortunately Prague’s stereotype of unfriendliness seemed to ring true in my experience. I had sent emails before arriving in Europe to the Charles University’s Jewish Studies Department as well with no response, so overall it was really difficult to try and get more personal information about Josefov from locals. As I was preparing for this trip, I was reading up on Prague’s Jewish history and found that while there were times of suffering, there were also times of prosperity, in particular during the 16th century. Visiting the Jewish Quarter today, I see that more than lives were destroyed in the Holocaust. A once thriving and active community of almost 1000 years abruptly vanished, and while never comparable to the loss of human life, I still felt an immense feeling of sadness to see that this event lead to the extinction of Prague’s Jewish culture.

Sarah Zdancewicz is currently a junior studying Business, Spanish and Comparative Religion at the University of Washington. She is originally from the desert oven also known as Phoenix, Arizona, but throughly enjoys the Seattle weather. She enjoys running, traveling, classic literature, and pictures of baby animals.

Leave A Comment