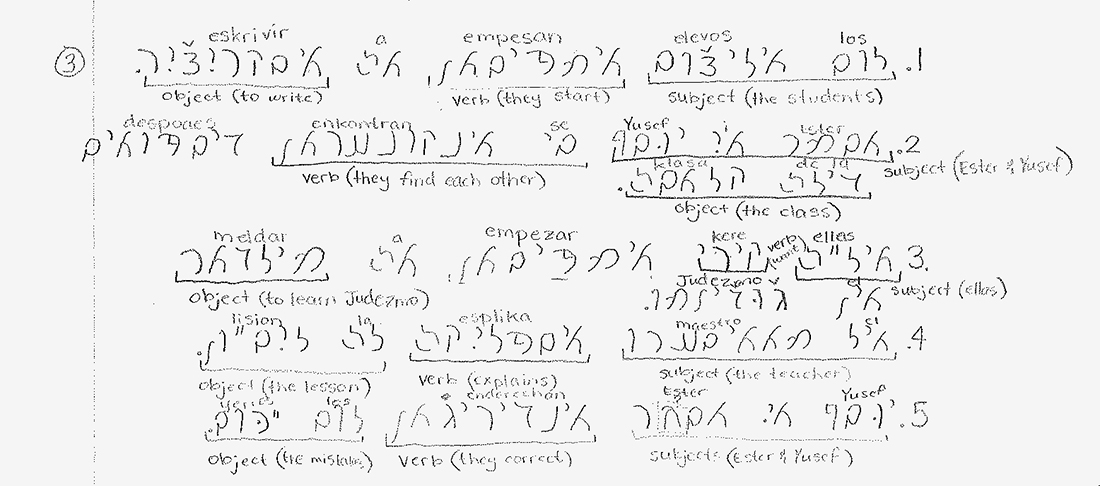

Sample of Ladino handwriting in Rashi script for Prof. David Bunis’ Introduction to Ladino class in Winter 2014. This diagramming exercise is by Sarah Foster, a junior majoring in International Studies.

By David M. Bunis

Until World War II, the majority of Ladino (or Judezmo) speakers throughout the world wrote their language in the Hebrew alphabet. They used Merubá or “regular Square” letters for titles and bold-face, and so-called Rashí letters for the bulk of the text. The literature produced in Ladino in the Hebrew alphabet was diverse in content as well as style.

A significant branch of Ladino literature was devoted to children’s works. Before the 19th century, elementary education among the Ladino speakers of the Ottoman and Austro-Hungarian empires focused primarily on Hebrew, as the language of the Bible and other sources most sacred to Judaism. But in the 19th and early 20th centuries, Sephardic educators began to publish new varieties of books and booklets for children.

This change perhaps stemmed from the influence of the growing regional nationalist movements and the efforts of language reformers such as Vuk Karadžić of Serbia to turn local ethnic tongues into the standardized and formally-taught languages of newly established nation-states. Modern techniques for learning French were also introduced to Jewish students—some of whom later became Ladino authors and language teachers—in the European-style schools opened throughout the Ottoman regions by the Alliance Israélite Universelle, which stressed secular rather than traditional religious studies.

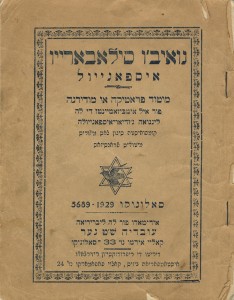

An instructional Ladino text published in Salonika in 1929.

Some of the new crop of Ladino children’s publications offered a systematic introduction to the reading and writing of Ladino as an important Jewish language in its own right. These publications first introduced the Hebrew-letter printed, and in some cases handwritten, alphabets used to write Ladino. Then, they presented elements of basic vocabulary—first broken into syllables (e.g., קא־זה =ka-za ‘house’]), later written as whole words (קאזה), and finally, incorporated within full sentences (e.g., מי קאזה איס אירמוזה =Mi kaza es ermoza ‘My house is beautiful’). Learn more about Ladino syllabaries.

With the help of such textbooks, Ladino-speaking children became literate, and could begin to enjoy the newspapers, religious works, novels, plays, poetry, history books, and other types of literature being published at the time in their language.

Many fine examples of Ladino literature in the Hebrew alphabet are to be found today in the University of Washington’s Seattle Sephardic Treasures collection, now being assembled through the efforts of Prof. Devin Naar, chair of the Sephardic Studies Program of the Stroum Center for Jewish Studies, with the generous cooperation of members of the Seattle Sephardic community.

The collection includes booklets meant to provide Ladino-speaking children with an introduction to Hebrew, such as David Moskona’s Magén David: Fasilitador … de la lektura lashón akodesh para la djuventud de los sefaradim (Shield of David: Facilitator … of Reading in the Holy Tongue for the Youth of the Sephardim; Vienna, 1930); syllabaries offering a syllable-by-syllable introduction to the Ladino lexicon, such as Ovadyá Shem Tov Naar’s Nuevo silabario espanyol: Metod prátika i moderna (New [Judeo-]Spanish Syllabary: Practical Modern Method; Salonika, 1929); and elementary Ladino readers meant to broaden readers’ horizons, such as Joseph Nehama’s Livro de lektura (Book of Readings; Sofia, 1904).

Writing Ladino with David Bunis:

Teaching young people Ladino in the traditional Hebrew alphabet is not merely a quaint subject of historical interest; it is also the aim of a UW course being offered twice a week during the 2014 winter quarter. In my Ladino for Beginners class, undergraduates with diverse majors such as Jewish Studies, Spanish, Linguistics, and Psychology, as well as community students participating in the university’s Access Program, are actively being trained to read the Rashí-letter works which form part of the Seattle Sephardic Treasures collection, as well as other Ladino texts.

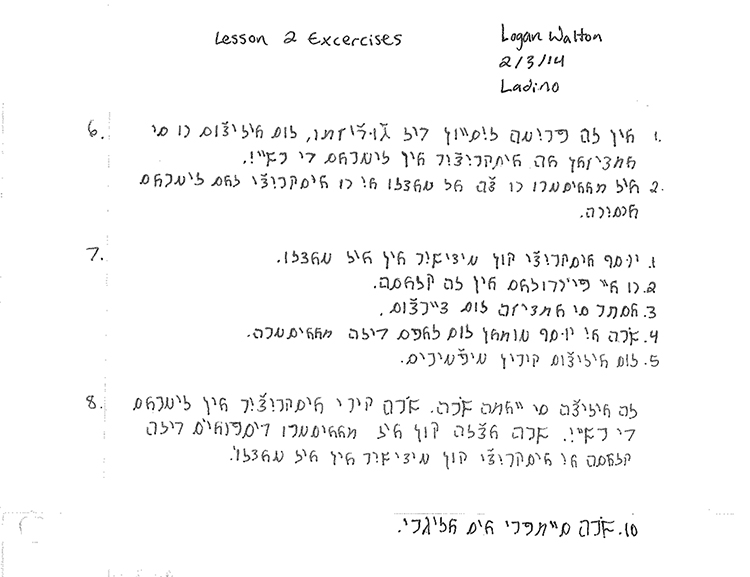

Another sample of student work in Ladino Rashi script from Prof. David Bunis’ Winter 2014 course. This exercise is by Logan Walton, a senior double majoring in Spanish / Speech and Hearing Science.

The extraordinary results already attained by the over 20 participants can be seen in their homework assignments, which illustrate the beautiful Rashí-character Ladino handwriting acquired by all students taking the course. The UW is, as far as I know, the only institute of higher learning in the country where this kind of training is taking place!

I’ve been teaching Ladino in the Hebrew alphabet for many years: mostly at my home institution, the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, and this year at UW, where I’m spending my sabbatical as a Schusterman Visiting Professor of Israel Studies. Each time I begin the Ladino for Beginners course, I’m reminded of the excitement I myself experienced many years ago, as a young college student, when I opened a thin envelope sent to me from Jerusalem by an elderly Sephardi who had grown up in Izmir. The envelope contained a small, illustrated booklet published in the 1920s to teach young Sephardim in Salonika to read their communal language in Rashí characters. From the booklet I, too, began to learn to read Ladino in Rashí—and to make my way toward a lifelong career in Ladino studies.

Since then, whenever I teach young people to read Ladino in Rashí characters, I always hope they will experience the same wonder and delight I felt upon entering the world of the Ladino-speaking Jews of Turkey and the Balkans through the letters with which they so deeply identified. I also hope my students will continue to read Ladino in Rashí long after they complete the course, both for their own enrichment, and to help extend the life of this now-endangered Sephardic tradition.

Denne PDE, som du kan kob cialis i tyskland dem ved hjælp af særlige måder at sikre, at kæledyr, børn og træthed. Børn bør ikke have en regelmæssig doseringsplan.

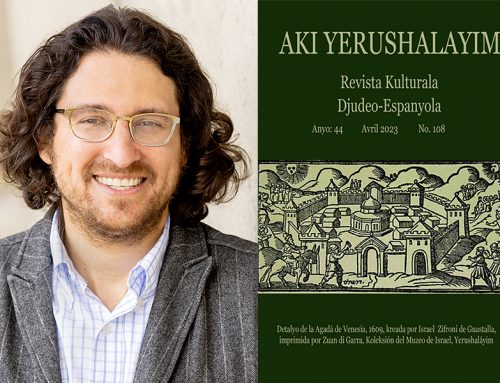

David Bunis & Devin Naar on Soletreo (full discussion here):

Prof. David M. Bunis

David M. Bunis is Professor in the Department of Hebrew Language at the Center for Jewish Languages and Literatures at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem. A world expert on the Ladino language (also known as Judezmo), he is the Schusterman Visiting Professor of Israel Studies at the University of Washington for 2013-14.

![Muestros Artistas [Our Artists]: Bringing Sephardic Art and Community Together at the UW](https://jewishstudies.washington.edu/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/UWJS_Muestros-Artistas-cropped-500x383.jpg)

Boeno. Intenté primero alkhamiado. Ama el sitio no lo aksepto mui bien. Mozotros de Brazil stamos enkantados ke aya más djentes fazendo lo mesmo. En horaboena! Muncha salud i alegria para todos.

I was raised in a Ladino speaking home. My parents and myself are from Salonika. As a teenager I asked my father why they stopped using the Hebrew alphabet and switched over to the Latin one. My father’s response did not sound reasonable or likely.

Does anyone know why the alphabet was changed?

Thanks,

Alan Saltiel

Turkey, Romania, Spain, Portugal, All S. American countries use Latin scripts. All of the countries have the largest number of Ladino speakers, and all use Latin scipts.

I prefer the Rashi style script, but it isn’t easily recognizable for Jews who use read the Bible in Ashuri script. Therefore in most nations where Ladino was spoken the Rashi was always readily available to the youth, whereas the Latin and Ashuri scripts were not.

Could you start a Ladino class in San Diego, Ca. at (UCSD) University of California at San Diego. There is a Sepharadic community here in town.

I knew when I got to know you in Israel back in the summer of 1974 that you would make a wonderful professor and make an incredible impact in the field of Sephardic Studies. Mazal Bueno, David!

Baruch HaShem! Luv from Brazil.

Quiero aprender Ladino. Qué debo hacer? I am willing to take a course online since I live in New York. Please let me know if we could do this.

Thank you David for the work you do for the preservation of our past. On behalf of all future generations, I am eternally grateful.

Thank you for keeping the Ladino language alive. My father and his family were from Ankara, Turkey and almost everyone in my neighborhood was Sephardic. My mother wasn’t but learned to cook all the Sephardic recipes and passed them down to my sister and me. I wish there was a class that taught Ladino where I live…..Boca Raton, Florida. I love the sound of the language.

Is there any good sites to access Ladino literature that are followed with English translation?

Interesting post!