By Sarah Zaides

How did Sephardic Jews learn how to read and write their mother tongue? And could the resources used then be helpful today for those who want to learn the language?

Judeo-Spanish (also referred to as Judezmo, Ladino, and Djudyo), the language of the Sephardic Jews of the Ottoman Empire, was not only an oral language spoken in the home or chanted in the synagogue. A vast array of books in Ladino indicate that it was also a language of written literature, religious and secular, didactic and entertaining, political and satirical, and more. Even if it was a written language, was Ladino ever taught like a proper modern language, with textbooks in schools? An array of original source materials collected as part of the Sephardic Studies Digital Library and Museum at the University of Washington reveals that, in the late nineteenth century and into the twentieth century, Jewish publishing houses across the Ottoman Empire issued a number of silabarios (sometimes called silavarios or silaberios), essentially small grammar books or school primers that taught children how to read and write in Ladino and to do so in the traditional Hebrew alphabet.

The three silabarios featured here come from the private collections of individuals here in Seattle who have kindly shared them with us. While one was published in Salonica (Thessaloniki), and two others in Istanbul (Constantinople), all three follow a remarkably similar structure. They tend to introduce the reader to the Hebrew alphabet (as used in Ladino), how to put the letters together to form sounds or syllables (hence the name of this genre of booklet: silabarios), and basic rules of grammar. These introductory sections are followed by short vignettes that provide moral lessons as well as introductions to Jewish holidays. Both practical and didactic, silbarios first made their appearance in the nineteenth century and new editions continued to be issued until at least the 1930s.

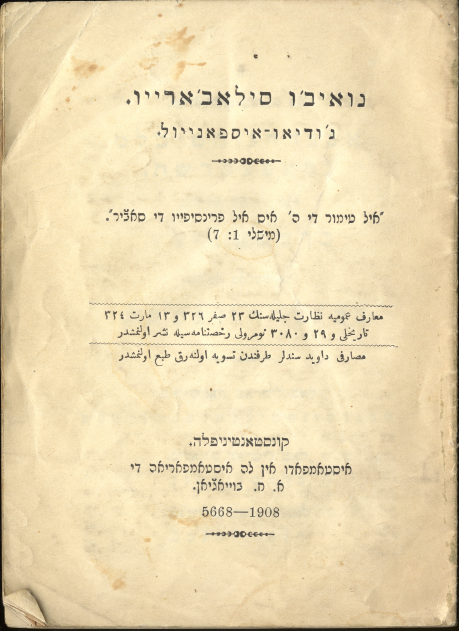

Nuevo Silavario Djudeo-Espanyol, Constantinople, 1908

Strikingly, scholars trace the seemingly unlikely origins of the first silabarios to interactions between Protestant missionaries and Jews in the Ottoman Empire. Beginning in the 1820s, Protestant groups from Britain and the United States influenced by millenarian beliefs anticipated that the upcoming 20th century would usher in the End of Days–a cataclysmic period in which Jews would play an important role. According to Christian sources, namely the Book of Revelation and the Book of Hebrews, Jews would eventually recognize the error of their ways, follow Christ, and return to the Land of Israel to usher in the Second Coming.

To promote this belief, Protestant missions established schools in the various cities of the Ottoman Empire. They also seem to have published the first silabarios. The first one, published in 1855, contained four short chapters, including a chapter on Rashi script, syllables, and reading comprehension passages. Due to the visibly Christian themes in these passages, scholar Rachel Saba Wolfe has suggested that missionaries composed and published them in the hope of attracting Jews to Christianity by making the tenants of the faith available to Jews in their own language, Ladino. During the nineteenth century, missionaries in the Ottoman Empire also published Ladino translations of the Hebrew Bible and of the New Testament, as well as biblical concordances and even a newspaper, with the same goals in mind.[1]

In response to the appearance of these missionary texts, Sephardic Jews decided to publish their own books in Ladino that would promote Jewish messages to the Jewish masses and counter the missionary propaganda.The silabarios featured here notably replicated aspects of the structure of the Protestant books, but, importantly, changed the content of the reading comprehension passages to reflect Jewish rather than Christian perspectives.

Equally as significant, these three exemplars appeared rather late: one in the final years of the existence of the Ottoman Empire, the second as the empire collapsed, and the third, on the eve of the Great Depression, in post-Ottoman Greece. Throughout this period, other languages had risen to challenge Ladino as the everyday tongue of Jews in the region for both practical and ideological reasons. In an era of rising nationalisms, some saw Judeo-Spanish as a kind of “impure” or “bastard” tongue–due to the admixtures of Turkish, Hebrew, French, Italian and Greek together with the Spanish–not suitable for proper discussion in modern times.

While Ladino continued to be spoken by the vast majority of Jews in the region, some proposed alternatives. Some preferred Turkish, the language of the Ottoman state; others preferred modern Hebrew, attracted by the new Zionist movement; and many, especially the upper and middle classes, viewed French as the language of modernity and of civilization. The Paris-based Alliance Israélite Universelle (est. 1860) aimed to educate Ottoman Jews in the European mold through a network of schools it established throughout the Mediterranean region. It is noteworthy, therefore, that despite the ascendance of the Alliance Israélite Universelle and the French language, Judeo-Spanish continued to receive attention among local Jewish educators and publishers, who deemed it necessary and worthwhile to formally teach Judeo-Spanish to Jewish youth [2].

Just as the first silabarios sought to convey the message of Protestantism to Jews in their local language, so, too, did proponents of the Alliance seek to convey its ideology and modernizing agenda to Jews in Ladino.

Take a look through our collection and ask: what were the priorities and expectations of the authors and publishers of these books? We’ve highlighted a few interesting passages, but please leave your comments and start a conversation.

A Spelling Book with Nursery Rhymes

The first piece, Nuevo Silavario Djudeo-Espanyol, or The New Judeo-Spanish Syllabary [Spelling Book], published in Istanbul in 1908 (the Hebrew year 5668) is a treasure for any young student of Ladino. From the library of the Sephardic Bikur Holim (ST00119), the booklet displays several languages on the cover: Ladino (in both the block and Rashi script) as well as Ottoman Turkish, the administrative language of the Ottoman Empire. The cover also includes a kind of epigraph drawn from Mishle (the book of Proverbs, 1:7): El temur de a'[shem] es el prinsipio de saver (“The fear of God is the beginning of knowledge”).

This statement sets up the tenor of the booklet, focused on a traditional education in the principles and practices of Judaism. But it also is very practical: from diphthongs, to verbs (importantes kon dos sylabios) to la biblia, this particular silabario seems most interested in helping children learn to read Ladino. Take for example a little nursery rhyme, Bolisa i su Gatiko, or “Bolisa and Her Kitten.” The syllables are broken up by hyphens, to aid in pronunciation and also to add a musicality to the nursery rhyme, a strategy meant to help the students memorize the story. “Mir-a al ga-ti-ko, ko-mo el es dju-ge-ton,” (“look at the kitten, see how he plays”).

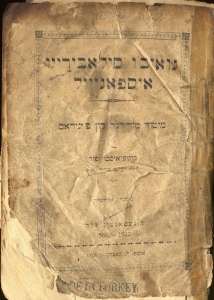

Nuevo Silabario Espanyol- Salonica, 1929

Nuevo silabario Espanyol: metod pratika i moderna por el embezamiento de la lingua Djudeo-Espanyola, kompuesta segun las mijores metodas fransezas was published in Salonica in 1929, or the Hebrew Year 5689. From the collection of Isaac Azose (ST006), the subtitle reads: the practical and modern method for learning the language of Ladino, composed according to the best French methods. Here the emphasis on the “best French methods” is of great significance for it advertises to the reader that the booklet should be perceived as up-to-date and European. The claim actually has the effect of legitimizing Ladino as a modern language by indicating that it can, in fact, be taught according to French methods.

(Notably, the publisher was a certain Ovadia Shemtov Naar. Despite sharing the surname with the UW Sephardic Studies chair, Devin Naar, there is no known family connection.)

The little grammar book contains everything from sounding out small words (el leon) to what happens on the first day of school. Interestingly, this silabario contains “hidden” moral messages, teaching its readers about good conduct and behavior in school and family, as well as basic Jewish morals. For example, a passage begins on page 22 about the first day of school: La manyana, el dia esklarese. El gayo kanta kukuriku (Morning, day breaks. The rooster crows cock-a-doodle-doo); it ends with a lesson that good children pay attention to their lessons. As another example, turn to page 35 for a lesson about honesty: el mentirozo no es nunka kreyido (one who lies is never believed).

The Salonica silabario also includes basic explanations for Jewish holidays (muestras fiestas). Notice that the author also uses the word fiesta and hag (Hebrew word for holiday) interchangeably. The descriptions are short, and include information about when the festivals begin according to the Hebrew date. It begins with the weekly Sabbath, Shabat (pp. 35-36):

La palavra shabat kiere dezir repozo.

Por kuala razon guadramos el Shabat? Por lo ke el Dio, despues de aver kreado el mundo en sesh dias, al de siete se repozo. Por esto mos ordeno el Shabat komo dia santa por repozarmos todo el puevlo. Aparte de esto, por akodrarmos del lavoro duro donde muestros padres sufrieron en Ayifto i muestro profeta Moshe demando este dia de repozo de el rey Paro i el Dio lo aprovo komo dia santa.

The word Shabbat means “rest.”

Why do we keep the Sabbath? Because God, after having created the world in six days, on the seventh, he rested. For this reason, he ordered the shabbat as a holy day for the entire people to rest. In addition, to remind ourselves of the hard labor that our ancestors suffered in Egypt, our prophet Moses also demanded that Pharaoh recognize this day of rest and God approved it as a holy day.

Nuevo Silaberio Espanyol, Constantinople, 1922 (second edition)

Finally, we have access to two exemplars of Nuevo Silaberio Espanyol: metod moderna kon figuras, printed in Constantinople in 1920 and 1922 (just prior to the declaration of the Turkish Republic). Both come from the library of the Sephardic Bikur Holim (ST00136 and ST00195). A set of inscriptions identify the former author of the book: “This book belongs to to Morris Maimon” (in English); and in the Rashi script of Ladino: “Este livro apartiene a Moshe Maimon tomado del Talmud Tora…” (This book belongs to Moshe Maimon taken from the Talmud Torah…”). The Talmud Torah likely referred to the Sephardic Jewish school that operated here in Seattle in the 1930s. Does this mean that the formal instruction of Ladino continued right here in the New World using the same textbooks as Jewish schools in the Old World?

Perhaps Morris Maimon was one of several students who studied from the book here in Seattle? If we turn to page 51, for example, we wonder: who is Victor Calderon, the name inscribed on the top of a page describing Jewish holidays?

Turn to page 44 to learn about el nasimiento de Moshe (the birth of Moses) and to page 48 for los diez komandamientos (the Ten Commandments)–in full. Notice that the Commandments are addressed in the informal second person, tu:

-

Yo so a'[shem], tu Dio, ke te saki de la tiera de Ayifto, de la kaza de siervos. No tengas otros diozes delantre de mi.

-

No agas a ti idalo, ni ninguna semejansa de loke ay en los sielos por ariva, ni de loke ay en la tiera por abasho, ni de loka ay en la aguas debasho de la tiera. No te enkorves a eyos ni les siervas, porke yo a'[shem] tu Dio, su Dio selozo, ke vijito el delito de los padres sovre los ijos, sovre los treseros i sovre los kuarentas djenerasiones, a los ke me aboresen; i ke ago mersed a miles, a los ke me aman, i ke guadran mis enkomendansas.

-

No djures el nombre de a”[shem], tu Dio, en vano, porke no livrara a'[shem] al ke djurara su nombre en vano.

-

Miembra el dia del Shabat para santifikarla. Sesh dias travajarash i aras todo tu ovra, ma el dia el seteno es Shabat a a'[shem] tu Dio, no agas ninguna ovra, ti, ni tu ijo, ni tu ija, tu siervo, ni tu sierva, ni tu kuatropedia, ni tu pelegrino ke esta adientro de tus puertas, porke en sesh dias izo a'[shem] los sielos la tiera, la mar i todo loke ay en eyos, i algo en el dia sinko; por esto bendisho a'[shem] el dia de Shabat i lo santifiko.

-

Onra tu padre i a tu madre, porke se alargen tus dias sovre la tiera ke a'[shem] tu Dio te da.

-

No mates.

-

No fornekes.

-

No roves.

-

No atestegues kontra tu kompanyero testimonio falso.

-

No kovdisies la kaza de tu kompanyero, no kovdisies la mujer de tu kompanyero, ni su siervo, no su sierva, ni su buey, ni su azno, ni ninguna koza de loke es de tu kompanyero.

Given the religious, didactic function of the booklet, it is no surprise that it also includes explanations of all of the traditional Jewish holidays just as the other silabarios do. This one is particularly fascinating because, under Fiestas Djudias, it contains an unexpected Jewish festival (p. 52): El 2 Novembre.

What holiday is to be celebrated on the 2nd of November? None other than the Balfour Declaration, the statement issued in 1917 by the British Foreign Secretary in support of the creation of a Jewish homeland in Palestine. It is the only “modern” holiday included in the Fiestas Djudias, indicating its significance from the perspective of the creators of this silabario, their support for Zionism, and their hope to instill in their readers, Jewish youth, the same political viewpoint.

The inclusion of the Balfour Declaration among the Jewish holidays is ever more striking considering the extent to which Jewish leaders in the former Ottoman Empire had explicitly opposed Zionism. The Chief Rabbi of Istanbul, Haham Bashi Haim Nahum, a protégé of the Alliance Israélite Universelle, initially viewed Zionism as a threat to the Ottoman Empire because its realization would entail the loss of Ottoman sovereignty over Palestine.[3] However, after the conquest of Palestine by the British in 1917, and especially with the formal institution of the British Mandate in 1922, support for Zionism among Turkey’s Jews would not comprise their loyalty to their own country as Turkey had already lost control of Palestine.

Although ostensibly a political statement, the booklet’s discussion of the Balfour declaration remains unquestionably shaped by traditional religious, even messianic, imagery:

Despues de muncho sufrir, muestro puevlo vido venir el dia de la salvasion. En el 2 Novembre 1917, un grande ministro Inglez, Balfour (rekordadvos bien este nombre), deklaro por la primera ves ke la Palestina apartiene alos Djudios. De dos anyos para aki, mozotros ya somos patrones de muestra tiera Eres Yisrael, la tiera ke prometio el Dio a muestros padres i ke mozotros pedrimos dos vezes. El Dio no se olvido de mozotros i el metio en los korasones de todos los reynados agora ke mos den a mozotros la Palestina. La fiesta de 2 Novembre es una grande fiesta para mozotros porke es el primer dia de muestra salvasion.

Translation:

After much suffering, our people has witnessed the arrival of the day of salvation. On the 2nd of November, 1917, a great English minister, Balfour (remember this name well), declared for the first time that Palestine belongs to the Jews. Two years later, we are already the patrons of our land, Eretz Yisrael, the land that God promised to our ancestors and that we lost twice. God did not forget about us and placed in the hearts of all the kingdoms today that they should give us Palestine. The holiday of the 2nd of November is an important holiday for all of us because it is the first day of our salvation.

From teaching the alphabet, basic phonetics and grammar, to lessons in morality, Jewish holidays, and even politics, the silabarios brought the world alive for Sephardic Jewish youth in their native tongue, Ladino. Those today seeking a glimpse into their world should explore these silabarios in greater depth. And those seeking to learn Ladino anew, in the twenty-first century, may find these little instructional manuals helpful, maybe even inspirational.

[1] Rachel Saba Wolfe, “From Protestant Missionaries to Jewish Educators: Children’s Textbooks in Judeo-Spanish.” Neue Romania 40 (2011), 135-151. [2] Rena Molho, “The Moral Values of the Alliance Israelite Universelle and their Impact on the Jewish School World of Morocco and Salonika,” El Presente: La Cultura Judeo-Espanola del Norte de Marruecos. December 2008, volume 2. [3] Esther Benbassa, Haim Nahum: a Sephardic chief rabbi in politics, 1892-1923 (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press), 1995.*This project was initiated with the generous support from the Digital History Fellows sponsored by the University of Washington’s Department of History.

Links for Further Exploration

- Tevye’s Ottoman Daughter in the Ladino Press by Sarah Zaides (Feb. 25, 2014)

- Why I’m Teaching a New Generation to Read and Write Ladino by David Bunis (Feb. 23, 2014)

Fascinating article. Ladino seems to be almost like Spanish. I found a narrative written by my aunt that said my great grandfather prayed in the “Sephardic shul” in Lubashava, Russia ( now Belarus) in the early 1900s. Would prayers have been in Hebrew or Ladino? And why would there have been a Sephardic shul in a shtetl in Russia?

Wonderful. Ladino was my first language, even thought I was born in Manhattan, Geography changed, but not the culture nor the values of our people. Honor, dignity respect and a quiet courage seems to have been passed down from many generations past. I am trying to pass it on to my children, grandchildren and now great grand children. Keep up the good work.