Members of the AnnaRF musical group

By Hayim Katsman

After the results of the Israeli elections in April, 2019, there seems to be a consensus among political commentators that liberal Zionism is dead. Liberal Zionists believe that a Jewish liberal democratic state cannot coexist with permanent military control over almost five million non-citizen Palestinians, and therefore a “two-state solution” is required. However, in these last elections, Meretz, the only Zionist party that explicitly supported this position, won only 3.64% of the popular vote, just slightly above the election threshold.

These results seem to support the position expressed by parts of the American and Israeli left, that they must choose between Zionism and a commitment to their liberal values. While this idea might be true in the institutional political sphere, I would like to show how Israeli reggae musicians offer a possibility of reinterpreting and reimagining Zionism to stand in line with liberal values.

Reggae’s cry for Zion

Reggae music has always been countercultural. Besides the well-known identification of reggae culture with the struggle for legalization of marijuana, reggae musicians also express anti-colonial messages and call for racial equality.

In the lyrics of reggae songs we can find protests against Western racial discrimination, capitalism and materialism. Reggae musicians’ protests against the West are not expressed only through the lyrics, but also in musical style. As opposed to Western music, which accentuates the first and third beats of every bar, reggae accentuates the second and fourth beats (or “off-beats”).

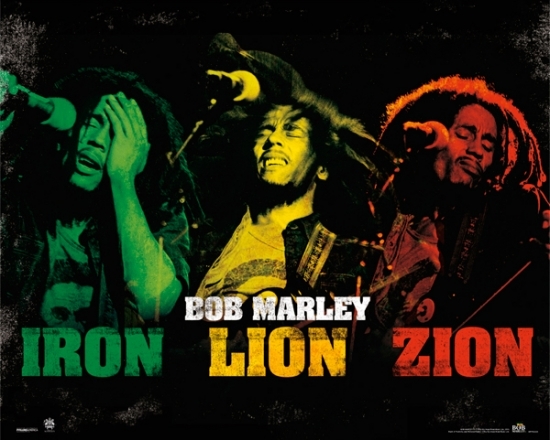

Moreover, in many reggae songs the drummer will not play the first beat of the bar, which gives reggae music a feeling of “floating” and is unusual in other musical styles. This unique rhythm (“riddim”) is called the “one drop,” referring to the “one drop rule” that was used for racial classification in America. This law asserted that any person with even one ancestor of African ancestry (“one drop” of black blood) is considered black. Bob Marley, singing “It’s all about the one drop,” reclaims the term and charges it with a different meaning.

Another interesting aspect of reggae is its fascination with Zion. In Rastafarian philosophy, “Zion” is the negation of “Babylon.” In the Jewish tradition, Babylon is a place of cultural confusion (as in the story of the Tower of Babel), but also the place where Jews were oppressed in exile, yearning to return to Zion.

Another interesting aspect of reggae is its fascination with Zion. In Rastafarian philosophy, “Zion” is the negation of “Babylon.” In the Jewish tradition, Babylon is a place of cultural confusion (as in the story of the Tower of Babel), but also the place where Jews were oppressed in exile, yearning to return to Zion.

In reggae music, Babylon is used to refer to anything in the world that is unjust – oppression, racism, capitalism, the state, the police, etc. Therefore, the reggae cry for Zion is a call for social justice and racial equality, and not necessarily for the physical land of Zion.

Similarly, the modern Zionist movement started as a movement against the oppression of Jews in the European diaspora and aimed to create a just society on the land of Palestine. “If you will, it is no legend,” the words of Theodor Herzl, leader of the political Zionist movement, are echoed in Bob Marley’s song “Zion Train,” where he states, “where there’s a will, there’s always a way.”

Reggae ideals in Israel

Despite the idealization of “Zion” in reggae, it seems as if the contemporary state of Israel does not live up to Rastafarian values. Today, leftist activists often see the state of Israel as an imperialist colonial force in the Middle East and equate Zionism with the oppression of the Palestinian struggle for national self-determination.

This poses a challenge also for reggae musicians in Israel who are opposed to Israeli policies. How can one sing about their yearning for Zion when they believe that Zionism has led to the oppression of other peoples? Should they make reggae music without referring to Zion? Is that even possible?

Israeli reggae bands offer us an example of a contemporary interpretation of Zionism that is opposed to racism and oppression. These bands do not view the contemporary state of Israel as the materialization of Zionism, but rather use Zionism to refer to a yet-unreached ideal. Just like early Zionist thinkers sought to end discrimination against Jews, Israeli reggae musicians reclaim Zionism in order to protest racial boundaries in Israel/Palestine.

Reimagining Zionism through Israeli reggae

ANNA RF, an ethno-reggae band from the southern Negev region, offers a vision of a world with no racial boundaries. Even the band’s name represents an attempt to blur linguistic categories — “Ana ‘aref’” is Arabic for “I know” and is an expression commonly used in Hebrew as a rhetorical question to say, “I don’t know.”

The band combines western beats with reggae rhythms, using traditional musical instruments like the oud and kamancheh. The band’s lyrics are written in English, Hebrew and Arabic, and band members pay careful attention to their physical appearance and stage performance so as not to identify with any particular religion or ethnicity.

In their last album, “Flight Mode,” the band included a song named “Called You Zion.” This song is inspired by the lyrics of a poem by an Ethiopian-Israeli social activist, Kassa Getoo, who wrote it in response to the Ethiopian community’s protests against police brutality in Israel.

Despite the fact that they are living in Israel, the singers express feelings of being in exile:

I called you Zion

But you are not responding, the call is waiting

I called you Zion

From the other side you have built me a wall

…

I called you Zion

When I will return to your borders I will rectify your dirt

I called you Zion

But your children do not see me in you

…

So let’s start it today

All from the beginning

The past is behind us

What’s done is done

So nice when you abolish categories

It’s the reality that appears when the illusion breaks apart.

This song represents a reclaiming of Zionism, from an idea of a Jewish sovereign state with special privileges for the Jewish people, to a vision of an exemplary society with no ethnic, racial or religious categories.

This kind of idea is gaining increasing support among Israeli society, but is not yet represented in the parliamentary political sphere. The spectrum of the Zionist / Israeli political imagination currently goes from those supporting the continuing Israeli control of Palestinian territories (and perhaps the eventual annexation of them) to those who advocate the separation of the land into two states — one Jewish and one Palestinian.

Building on the concept of Zion in reggae culture — as opposition to “Babylonian” systems of racial boundaries and oppression — can enable the reimagination of the Zionist ideal, and can perhaps open new possibilities for political solutions in the region, as well.

Understand this first please before you confuse the struggle, this has nothing to do with Israel, however they speak about the fight for the oppressed in Gaza region.

In Jamaican and Rasta religion, Zion is Africa, and nothing to do with Israel. Black people are yearning to return home to Africa… Ethiopia is where Rasta’s believe is home.

sounds like Trish didn’t actually read the article