Luther Adler, Stella’s brother, and Stella Adler, in a publicity photo for the play “Awake and Sing!,” 1936. Via Wikimedia Commons.

By Amna Farooqi

If you’re like me and ran to the theater to see director Yorgos Lanthimos’ most recent film release, “Poor Things,” starring Emma Stone, Willem Dafoe and Mark Ruffalo, you may not have guessed that one of these actors has strong ties to the Yiddish theater.

That’s right: Actor Mark Ruffalo, of “13 Going on 30” fame, received his acting training from a woman who is not only descended from Yiddish theater royalty, but has also become famous in her own right for her acclaimed acting Method. I am talking about none other than the famous actor and teaching icon, Stella Adler.

Stella Adler and the origins of method acting

Stella Adler was born to Jacob P. Adler and Sara Adler in New York City’s Lower East Side at the turn of the 20th century, in 1901. Both of Adler’s parents were originally from Odessa (in what is now Ukraine) and emigrated to the United States: Sara in 1883, and Jacob in 1890.

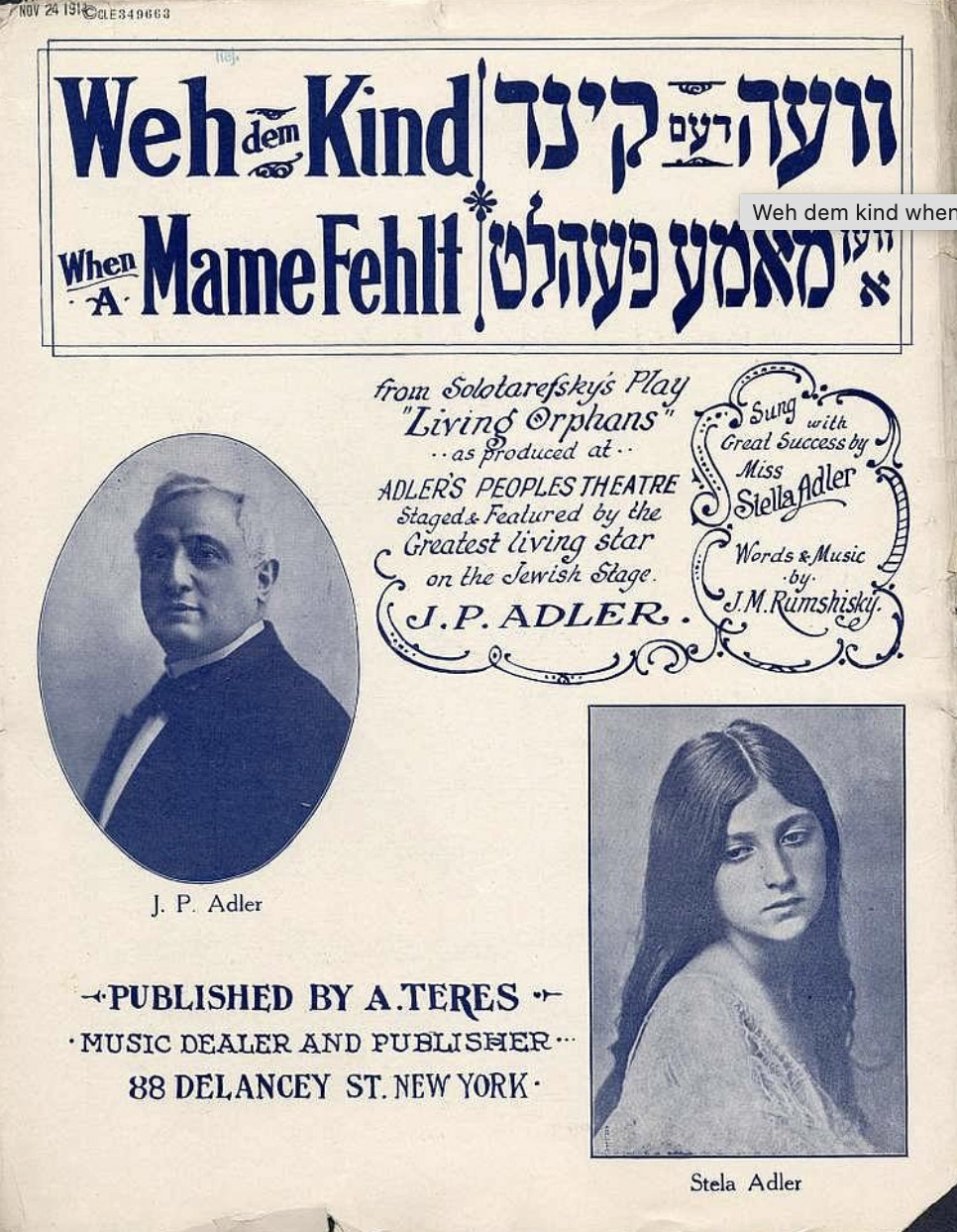

Cover of the sheet music for a popular Yiddish song, Weh dem kind when a mame fehlt, 1914. “From Solotarefsky’s Play ‘Living Orphans,’ as produced at Adler’s Peoples Theatre, Staged & Featured by the Greatest living start on the Jewish stage, J.P. Alder; Sung with Great Success by Miss Stella Adler.” Via the Library of Congress.

They would become two of the most prominent actors in New York’s Yiddish theater, which was the premiere theater district in New York City at the time. It was also the precursor to what we have come to know as the height of American theater: Broadway.

Like their parents, Stella Adler and her five siblings were quick to take to the stage. They began acting at a young age; so perhaps it makes sense that Stella Adler would go on to open her own highly acclaimed acting studio. She would also produce one of the most common forms of acting training used in U.S. higher education institutions today.

Tracing the lineage of Adler’s acting method provides important insights into her craft, which is used by actors worldwide today. Whether it’s sitting down on a couch to stream a show, watching a film in a movie theater, or attending an evening out at a repertory theater, you’re likely encountering an actor who has engaged her version of method acting in their career.

Yiddish theater comes to the United States

Yiddish theater was performed in the language of Yiddish, a language related to German that was spoken by most Ashkenazi Jews — i.e., Jews who lived in northern Europe, eastern Europe, or present-day Russia — for many centuries.

Modern Yiddish theater can be traced back to 1876 in Romania, with the work of playwright Avrom Goldfadn. In 1879, Goldfadn created a Yiddish theatre troupe that performed in Odessa. During the two decades following, Yiddish theater began to appear in London, New York, Philadelphia and Chicago alongside the migration of eastern European Jews, including playwrights and actors, who were fleeing pogroms and increasing economic instability in the early 1880s in the Russian Empire.

According to Yiddish theater scholar Joel Berkowitz:

Yiddish theatre [in New York] provided a running commentary on the lives of central and eastern European Jews and their descendants… Ideological differences within the Jewish community, persecution from without, mass migration across Europe and on to other continents, the quest for a Jewish homeland, the tension between accommodating to changing social conditions and adhering to one’s own religious traditions— all the central themes in the modern Jewish experience were dramatized in the Yiddish theatre.

In the earliest stages of New York’s Yiddish theater, productions included adaptations of Shakespeare’s works, as well as original works by Jewish playwrights living in New York. Actors like Jacob P. Adler, who first rose to success in Odessa, helped to establish a Yiddish theater district in New York City’s Lower East Side.

Theaters of experimentation

The Yiddish theater was deeply integrated into the Jewish immigrant community that lived in the surrounding area. Unlike today, where you might leave a Broadway show and head towards the stage door in the hopes of meeting your favorite starlet, you’d likely find a star of the Yiddish Theater to be much more familiar as a fixture within your own community.

More importantly, perhaps, is that the theater served as a space of experimentation. According to Edna Nashon, who curated the exhibition “New York’s Yiddish Theater: From the Bowery to Broadway” for the Museum of the City of New York in 2016 and edited an accompanying book, the Yiddish theater was a place where Jewish migrants could “experiment with their Americanness within the imaginary confines of the space of the stage.” In other words, they could portray issues they were facing as new immigrants, both resisting and assimilating to American culture, and work them out onstage.

This sort of socially conscious theater likely primed Stella Adler to join The Group Theatre, out of which her acting method would evolve.

Group Theatre company photo, 1938, New York City. Includes Roman Bohnen, Luther Adler (Stella Adler’s bother), Leif Erickson, Frances Farmer, Ruth Nelson, Sanford Meisner, Phoebe Brand, Eleanor Lynn, Irwin Shaw, Elia Kazan, Harold Clurman and Morris Carnovsky. From Stage magazine, December 1938, volume 16; via Wikimedia Commons.

Though she had practiced acting under her parents’ tutelage throughout her childhood and into her adolescence, Stella Adler started training with the ensemble theater company known as The Group Theatre in 1931. The Group Theatre emphasized communist ideals, both on and offstage. They were a remarkable example of a true commune at the time; they lived together in what Harold Clurman, one of the members and Stella Adler’s husband, affectionately referred to as “Groupstoy,” a ten-bedroom shared loft on 57th Street between 9th and 10th Avenues in Manhattan.

And since they were an ensemble theater collective, in addition to sharing income, they shared acting roles (fairly) evenly across their work. In 1934, they would produce one of their most renowned productions: Clifford Odets’ “Waiting for Lefty.” A play about the New York Taxicab Union Strike from 1934-35, it famously ended with the audience breaking the fourth wall. Spectators rose from their seats to chant, “Strike!” along with the characters onstage.

It was within this politically charged environment that Adler learned a version of famous Moscow Art Theatre director Konstantin Stanislavsky’s “Method” of acting, from which she would eventually derive her own.

Meeting Stanislavsky & the Method

Dissatisfied with the version of acting that her Group Theatre colleague Lee Strasberg (with whom she often vehemently disagreed) was imparting, Adler went straight to the source. In 1934, she arrived in Paris to study acting directly with Stanislavsky himself. Upon her return, she brought back Stanislavsky’s ideas to make something of her own: a new, American Method of acting. So, what is an acting “Method”?

At the turn of the century, the style of theater we call “realism” was at its height. Freudian psychology, which emphasized a person’s individual struggles and inner life, was becoming popular and audiences wanted to see inner workings of middle-class characters onstage. This is reflected in popular dramas of the day like Anton Chekov’s “The Cherry Orchard” and Henrik Ibsen’s “A Doll’s House.”

Stella Adler in the 1941 film, “Shadow of the Thin Man.” Via Wikimedia Commons.

One approach to getting to the interiority of a character is through Method acting. Versions of Stanislavsky’s system are referred to as the “Method.” Stanislavsky’s Method was a system of techniques that would allow an actor to access the most truthful portrayal of a character. While Lee Strasberg famously required actors to draw on their own personal experience, traumatic or otherwise, to portray a character onstage (emotional recall), Adler worked to preserve the psychological health of the actor.

As opposed to employing emotional recall, Adler’s system required using one’s imagination to facilitate realistic behavior under “given circumstances.” Scholar Rosemary Malague defines the “given circumstances” best when she tells us, “If an actor works within the circumstances of the play, and chooses the right actions (something to ‘do,’ or an effort to be accomplished; onstage choices founded through careful script analysis)— with imagination — the justification will elicit emotion.” That emotion, once elicited, will find expression in the body of the actor.

Take, for example, an actor playing the strike leader in Clifford Odets’ “Waiting for Lefty.” Their action, according to Adler, might be to denounce their employer, under the given circumstances of the play’s narrative. The actor playing the strike leader, having done careful script analysis to define this action within the context of the entire play, would be able to elicit the correct emotion when their character calls for a strike at this particular moment within the drama.

American “method acting” today

In 1949, Stella Adler opened her own acting studio in New York City called the Stella Adler Theatre Studio (now: the Stella Adler Studio of Acting), eventually expanding to open a location in Los Angeles as well.

Notably (and not only because it is my alma mater), there is an entire division of NYU’s Tisch School of the Arts dedicated to Stella Adler’s Method, and there are classes across the country in various institutions where her Method is taught.

As the only American to bring back Stanislavsky’s Method directly from the source, Adler’s contribution to American acting is an important one that will continue to shape acting and artistic performances for years to come.

Amna Farooqi is a doctoral student in the School of Drama at the University of Washington. Her research broadly focuses on identity and representation onstage, with an emphasis on examining minoritarian performances through frameworks of transnationalism and empire, specifically migrants and refugees. She has presented her work at the American Society for Theatre Research (ASTR) and the Mid-America Theatre Conference (MATC). She holds a B.A. in Individualized Study from NYU’s Gallatin School as well as an M.A. in Performance Studies from NYU’s Tisch School of the Arts. She is the 2023-2024 Max Sarason Fellow in Jewish Studies.

Amna Farooqi is a doctoral student in the School of Drama at the University of Washington. Her research broadly focuses on identity and representation onstage, with an emphasis on examining minoritarian performances through frameworks of transnationalism and empire, specifically migrants and refugees. She has presented her work at the American Society for Theatre Research (ASTR) and the Mid-America Theatre Conference (MATC). She holds a B.A. in Individualized Study from NYU’s Gallatin School as well as an M.A. in Performance Studies from NYU’s Tisch School of the Arts. She is the 2023-2024 Max Sarason Fellow in Jewish Studies.

![Muestros Artistas [Our Artists]: Bringing Sephardic Art and Community Together at the UW](https://jewishstudies.washington.edu/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/UWJS_Muestros-Artistas-cropped-500x383.jpg)

Such a lovely article. Had more been written, I could have spent a great amount of time reading. Great subject, great writer!