Illustration from the Darmstadt Haggadah showing Jewish men and women discussing the Exodus story, ca. 1430, Germany.

By Kerice Doten-Snitker

Centuries of anti-Semitism have perpetuated stereotypes about Jewish people and financial success. These stereotypes are so strong that they often get projected farther and farther back into the past, as if they were timeless descriptions of Jews.

Based on present-day stereotypes, Jews are sometimes believed to have been elite financial professionals and merchants throughout history. But Jews in medieval times were not categorically the exceptional financiers and traders these myths suggest.

Trade in late medieval Europe

In the late medieval period (1250CE-1500CE), commerce and finance were blossoming in Europe. Goods were exchanged between one end of the continent and the other. Ships zipped across the Mediterranean, along the Atlantic coast, through the North and Baltic Seas, and up and down rivers like the Rhone and the Rhine.

Some cities and communities began specializing in long-distance trade. Records from the Cairo Genizah storehouse of medieval documents testify to the extensive trade network of Maghribi (North African) Jews. But Jews were not unique in running commercial enterprises, nor did Jewish traders dominate the Mediterranean. Among the most well-known and powerful merchants of the era were the Christian traders of Ragusa (today Dubrovnik, Croatia), Venice, Genoa, Valencia, Catalonia, and the Knights of Malta. Italian traders and the Hanseatic League were most dominant in the Baltic and North Sea.

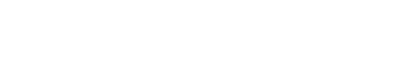

16th-century Christian German banker Jakob Fugger and his principal accountant, M. Schwarz. The file cabinet in the background shows the European cities where the Fugger Bank conducted business. 1517.

The most successful merchant communities developed reputations and identities as foreign commercial experts. “Foreignness” was a commercial advantage for traders because it communicated to customers that they had a wide reach and some credibility as merchants in other cities. Being foreign implied that traders traveled long distances and, importantly, were prepared to deal in multiple currencies.

Like in Europe before today’s European Union agreed to use the Euro to simplify trade and exchange, different regions and towns in Europe used different currencies in the medieval era.

Because long-distance traders traveled between places with different currencies, and because it was difficult to move and exchange coins between these places, these long-distance traders were central figures in developing European money markets for currency exchanges and guaranteeing that money deposited with them in one city could be transferred to another merchant in another city to pay for goods, land, or services there. In fact, foreign exchange through merchant family companies like the Italian Medici family and the German Fugger family built the first European banks.

The role of Jews in commerce and finance

There were no extensive continental Jewish trading networks that rivaled the Christian ones of medieval Europe. This is not to say that no Jews were involved in financial or trading professions. Historical records name many Jews dispersed across Europe whose livelihoods involved money and trade. It is well-documented elsewhere that Jewish cultural values of reading and learning prepared them well for medieval urban life and occupations, including commerce, at a time when literacy and schooling were not universal. But Jewish merchants were mostly active locally and regionally, as familiar members of their communities.

Some Jews were involved in small transactions with common folk. Everyday people in towns across sought loans or pawned possessions in order to afford necessities, like replacing tools in their workshops. For instance, in the region of Lucca, Italy, Jewish lenders played the role of middlemen between the urban world, where money and goods moved freely, and the rural world, which lived at the edge of subsistence with very little access to credit.

The wax seal of Muskinus Daniel. From Medieval-Ashkenaz.org.

Some Jews were involved in large transactions for the rich and powerful. The Archbishop of Trier Balduin of Luxemburg (in office from 1307-1354) relied heavily on two Jews, Muskinus and Jakob Daniel, to provide credit and manage the transactions of the Archbishop’s court.

If some medieval European rulers employed Jewish financiers, it was because they, like their Christian counterparts, were financially successful as individuals. The majority of rulers relied on Christian financiers, like the Fuggers of Augsburg, Gerhard Unmaze in Cologne, the Le Gronnais family in Metz, and various other nobles and gentlemen.

Jewish lenders’ biggest advantage: Not being elite

While Christians treated Jews as a community of different origins and values, it was not the sense that Jews were from or belonged to some other land that made borrowing from Jews attractive. For the most part, Jews were not strangers in their towns; their families may have lived there or nearby for several generations.

If medieval Jews had one advantage in participating in the financial business of elites, it was the perception of their neutrality: They were not engaged in the Christian political conflicts that pushed elites to borrow money. Unlike Christian financiers whose business catered to the powerful, Jews could not use finance and credit to create influence and patronage among Christian elites.

For example, in 1359, the elites of the town of Andernach needed to raise funds to pay debts to the powerful Archbishop of Cologne, with whom they had been in conflict for the past few years. Rather than borrowing from Italian financiers, who were already involved with financing the Archbishop and the Catholic Church, the Andernach elites borrowed from the Jewish Bonefant family of Koblenz, a city about 20km away that was home to the second largest Jewish community in German lands.

Debunking the myth of “elite” medieval Jews

Modern anti-Semitic stereotypes portray Jews as innately skilled in financial professions, and conspiracy theories extend these stereotypes, by ascribing power and nefariousness to any individually successful Jew.

The reality of medieval European Jews — that, just like Christians, a handful were successful merchants and financiers, but that the majority led economically mundane lives — disrupt these assumptions about the financial history of Jews, helping to dispel these damaging myths.

Kerice Doten-Snitker, Rabbi Arthur A. Jacobovitz Fellow, is a doctoral candidate in sociology at the University of Washington. She double-majored in sociocultural studies and international relations at Bethel University (Minnesota) before completing an M.A. in sociology at the University of Washington. Her scholarly interests include processes of inclusion and exclusion in society. Her current work examines the roles of political institutions, economics, and religion in the exclusion of Jews in medieval times, focusing on the Rhineland (western Germany). In fall 2017 she was a visiting student at the Arye Maimon Institute for Jewish History at Universität Trier in Trier, Germany, funded by the Deutscher Akademischer Austauschdienst (DAAD). In addition, she works at the University’s Center for Evaluation and Research for STEM Equity, which focuses on increasing equity — and the participation of systematically excluded students and professionals — in the fields of science, technology, engineering and math.

What about the Radhanites or the fact the church discouraged Christians from pursuing money lending, leaving room for Jews to pursue such fields? What about the group of Jewish merchants sent to England by William the conqueror after he defeated England in the battle hasting in 1066? It would seem the small percentage of Jews who did participate in money lending managed to make a name for themselves.

It’s an interesting read, but this article has omissions and inaccuracies and sounds like an apologia.

My overall impression is that you’re trivializing the role of the Jews in finance and trade, in medieval and post-medieval Europe trying to make them look just like your average guy next door, “criminalizing” being successful, and trying to prove that they were really not that successful or important. But the Jewish role and contribution were completely disproportionate and yes, exceptional, relative to their small numbers. Stereotype or not, I couldn’t care less. There is nothing to be ashamed of.

Next, what’s “elite” in MEDIEVAL Europe? Elite was titled landed gentry, i.e. aristocracy, followed by top church hierarchy. As a rule, Jews were not in either category, by definition so we could end the “straw-man” argument there. Merchants/bankers didn’t become “elite” until much later, generally post-renaissance times, and some places not until 19th century. Being wealthy and being elite are not necessarily the same. Even the Medici had to ennoble their humble merchant pedigree by becoming the Dukes of Tuscany. Also, what’s wrong with being “elite”? Jews seems to be “elite” in many fields (not just banking or finance) and it doesn’t seem to bother even staunchly anti-elitist communists.;)

Jews were certainly and often enough a relative “elite” in the business world, but it depended on time, place and sector. I don’t see anything wrong with it (not more wrong than being disproportionally represented in medicine, science, law and chess, to mention just a few areas), and I certainly don’t think that Jews should apologize for their disproportionate success.

You stated that “The majority of rulers relied on Christian financiers”. This is an awfully general statement. Depends when and where. Economic opportunities, market conditions, competitive landscape and restrictions were different in different times and places. Christian rulers did employ Christian financiers, when and where they were available. The problem was that for most of the Middle Ages and in most of Europe they were not that readily available, with exception of most widespread pawn-broking that had some Christians involved in it (e.g. Lombards and Cahorsins), and also Jews.

The Christian prohibition on lending with interest was the prime reason. There were other reasons, too. Jews filled the gap especially for large scale finance, often being the major or the only source of finance both to the rulers and the church. Not everywhere and not always, but in many places and at many times. Not because they were perceived “politically neutral” and certainly not because the borrowers had this modern propensity for “buying local” (although it helped, I’m sure). Also, Jews were easier to manipulate and blackmail. Look up forced loans. Also, I suggest you re-read the Merchant of Venice.

Aaron of Lincoln (whom you curiously omitted) ran the biggest English banking “empire” in his 12th century (likely not surpassed for centuries after his death). He financed major building projects, from cathedrals to castles and palaces and was likely wealthier than the king. It wouldn’t be inaccurate to say that at some time periods and in some places Jews were the major catalysts of economic development, not only in terms of infrastructure finance but in terms of trade finance and trade itself as well.

The rise of Italian christian banking (especially in Florence and Siena) in High Middle Ages (12/13th century onwards) put Jews at certain disadvantage (especially in Italy), where laws were also enacted against them that relegated Jews to small-scale pawnbroking and second-hand goods (mostly clothing) trading, while Italian catholic banks like Bardi, Scali, Peruzzi and later Medici took a full advantage to scale up their operations.

In addition to loans, Jews were heavily involved in money-changing, tax farming, customs farming, estate management, relic trading, luxury/high value goods trading. Again, depends on when and where. Look up Radhanites, for example who were absolutely instrumental in the trade between Europe, North Africa, Middle East, India and China long before Marco Polo and Venetian or Genoan merchants..

Finally, I’m amazed how deep-seated the stigma of “usury” is in the minds of many people. But they forget that interest rates were not only frequently regulated, but they’re also a function of risk. How many times Jews were expelled with their assets confiscated and the debts to them waived on some flimsy pretexts, often when those rulers were about to default?

Hi Robert, I think you misinterpret the points of this essay. There is a misconception that elite financial actors were limited to Jews (elite in the sense of largest value and clientele), which also fuels antisemitic conspiracies and stereotypes about present-day Jewish people. Christian financial elites, and economic elites more broadly, certainly existed in late medieval Europe. In fact, conflicts between these elites and the nobility played into the foundation of representative bodies in cities in the High Middle Ages. Jewish financial actors may have had notable success in business (and I do not shame that), but telling a supposedly general European economic history by focusing on Jewish activities misses the crucial point that most lending came from Christians – in part because the ostensible ban on lending at interest could be interpreted to carve out some levels of interest, or interest in certain scenarios. You might be interested in the new book ‘No Return’ by Rowan Dorin, describing the regulation of Italian and Jewish financial activities in parallel.

Interesting article and comments that followed. I do believe Jewish financiers were responsible for financing the construction of many cathedrals in Europe which would otherwise have not been built.